In the foodservice world, most multiunit franchise companies are content with filling out their portfolio with a suite of franchised brands. Fast-casual industry taking off? Sign on with one of the hot new upstarts. Need a pizza concept to complement your offerings? There are dozens of options available.

But Aurify Brands isn’t most multiunit franchise companies. The New York City–based firm that launched as a Subway franchisee in 2003 and eventually became the only Five Guys franchisee in Manhattan chose not to grow exclusively through franchised brands, but rather with both franchise partners and proprietary brands.

Today, Aurify—the word means “to turn to gold”—operates four such brands. There are three Fast Casual 2.0 concepts—The Little Beet, Melt Shop, and Fields Good Chicken—as well as a full-service restaurant, The Little Beet Table. Each concept is guided by its own managing partner; cofounders Franklin Becker and Andy Duddleston serve as managing partners for The Little Beet, while founder Spencer Rubin manages Melt Shop and Field Failing does the same for Fields Good Chicken.

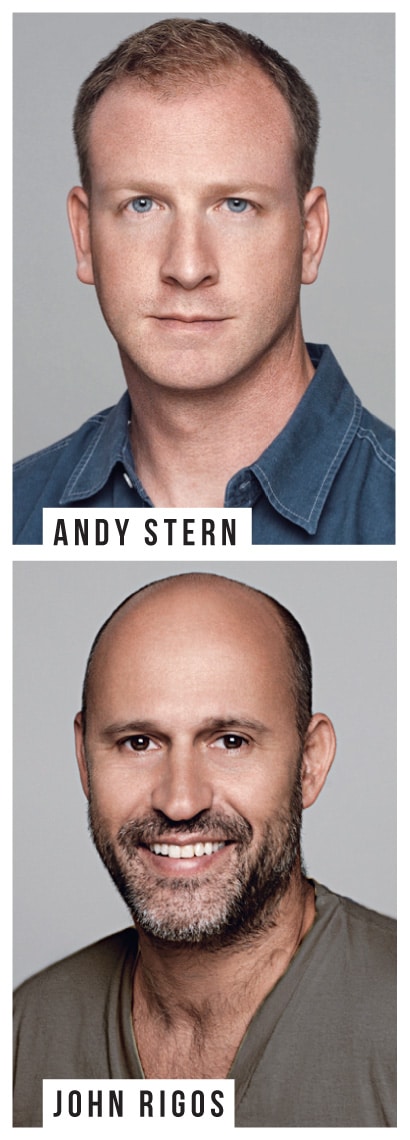

Aurify cofounders and co-CEOs Andy Stern and John Rigos spoke with QSR about what they’ve learned from the franchise world, how they’ve used those lessons in their proprietary work, and how they’ve built an organization that incubates new ideas and leverages resources across a robust system.

How did Aurify come to be?

Andy Stern: John and I had worked together before in the technology world. Then we did some back-and-forth investing in different opportunities we had when we left those jobs. John bought a farm in upstate New York, and in that town where he was, people in the town were saying they wanted a Subway. So the thought process was: “Sure, let’s open one. How hard can it be?” Obviously, now we know it’s extremely hard, and thankfully it was with someone like Subway, who was really the grandfather of all franchising, as far as systems go, and being able to teach you.

From there, we saw an opportunity to learn more. There’s less risk, clearly, if you’re a franchisee than if you’re an original concept, because somebody’s already done the hard work in figuring all the business processes out. They most likely have all the contracts you need for purchasing. The better franchisors have done the homework as far as, here’s what scheduling should look like, here’s your optimum output and productivity levels based on sales, and here’s how you prep. We went from Subway to Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins. Then we got involved in Five Guys. Each one brought different things to the table as far as franchisor went. That really taught us a lot about the breadth of being a good franchisor.

From there, we saw an opportunity to learn more. There’s less risk, clearly, if you’re a franchisee than if you’re an original concept, because somebody’s already done the hard work in figuring all the business processes out. They most likely have all the contracts you need for purchasing. The better franchisors have done the homework as far as, here’s what scheduling should look like, here’s your optimum output and productivity levels based on sales, and here’s how you prep. We went from Subway to Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins. Then we got involved in Five Guys. Each one brought different things to the table as far as franchisor went. That really taught us a lot about the breadth of being a good franchisor.

John Rigos: I think it’s important to go a little bit further back. Andy and I met at a technology incubator, Idealab, and the whole premise was that there was a collective infrastructure that supported new-idea generation and helped test what businesses were viable. Yes, our first foray was as passive investors in the Subway franchise, then more actively in the Dunkin’ franchise. And then obviously we’re deep into Five Guys. But we always wanted to re-create the Idealab incubator model, using real-world businesses—brick-and-mortar-type businesses—to be developed rather than just technology companies.

The way Aurify has been structured is a common infrastructure with functional areas—accounting, finance, marketing, construction, HR, all that stuff—and our whole premise is that we can, with this collective knowledge, begin to develop new brands that focus on a specific market need within the fast-casual segment.

You’ve since exited the Subway and Dunkin’ franchises. Why exit? Why not build out the franchise portfolio more?

AS: Ultimately, for the two of us, we’re very entrepreneurial, and the downside to franchising is it’s very operationally driven and it’s not really pulling on your strategic insights and strategic capabilities.

JR: Or allowing you to be creative.

AS: Or being creative, yeah. So setting strategy both from a creative and menu side, and then setting all your business processes in-house, those are all checked at the door when you sign up for a franchise, which is part of the benefit of being a franchise: You don’t have to worry about that stuff. But that’s the stuff we like, and the stuff we think we’re pretty good at. It felt somewhat constraining to be in an environment where we weren’t allowed to use those skills. That’s really where we started thinking about making a pivot and developing some of our own brands, and the fact that we should own the intellectual property at the end of the day.

When you decided to open your own proprietary brands, did you have in mind what type of restaurant you wanted to open? What was that decision like?

JR: We were looking for holes in the existing marketplace. Obviously, sandwiches are one of the biggest categories in fast casual, but most of the sandwich concepts are derivatives of Subway. Melt Shop was our first foray into developing our own concept because we saw that there was really a need for artisanal sandwiches beyond your neighborhood deli, in a format that could be rapidly expanded and rolled out nationally—one that doesn’t just elevate the whole experience, but focuses on offering warm sandwiches, which I think is a great category.

Then the whole health thing started happening, so there was a huge opportunity to go with a healthy concept that was fast food. And that was something that historically nobody even thought was possible. How do you offer healthy food, which is generally more expensive, in a fast-food format and environment? That was when we partnered with Franklin Becker, our executive chef. He’s really big on the healthy category in terms of fine dining, but he wanted to transfer that knowledge into the fast-casual world. So we partnered with him in 2012 and launched The Little Beet.

That is the category that is most exciting, because people are becoming increasingly discerning about what they eat, where the food comes from, being healthy day to day. So we started looking for more opportunities there. That’s when we met Field Failing, who had the idea for Fields Good Chicken, which is basically the better-chicken category, which doesn’t even exist today. So that’s when we partnered with Field to do the same thing, catering to that healthy fast food category, with Field as our partner.

[pagebreak]

What role do the partnerships with people like Failing, Becker, Duddleston, and Rubin play in Aurify’s success?

JR: It’s fantastic, I’ve got to tell you. This is a lesson Andy and I learned when we were at Idealab. I remember [founder] Bill Gross at Idealab saying, “You know what, I can come up with ideas all day that are great. Unless someone actually owns the brand and manifests all the important aspects of the brand themselves, it really won’t work.” We knew that Andy and I couldn’t necessarily start any of these concepts unless we had an operating partner that felt the same way about what we were trying to accomplish and really owned it and drove the brand. Our responsibility is really to ensure they have everything they need, from a resource standpoint—capital, human, strategic, all that stuff to power them to be successful.

You’re starting to open in other markets, including Washington, D.C., and Chicago. What kinds of markets offer the best potential for your brands?

JR: We love New York City, and there’s no market like it, so we absolutely want to saturate all our brands in this market. But it’s very expensive, and it’s very competitive to get that 2,000-square-foot box; we’re competing with a lot of other people. We didn’t want to slow down our growth by waiting patiently for the right sites. So we figured, you know what, while we want to focus on New York City, we do want to get to other markets like Washington, D.C., Chicago, or whatever. Why don’t we start planning on going there now and concurrently developing markets simultaneously?

Some people say you should focus on a given market. That makes sense, but we also have expansion plans that we want to realize, and we felt that it was prudent to start establishing a presence in other markets while we continue to focus on New York City. If you have a great operating partner in a market, they can handle it, even if they may be 1,000 miles away. We have a whole infrastructure here to support them.

A LOOK INSIDE

Breaking down Aurify’s three fast-casual concepts.

The Little Beet

Units:

5

Menu mantra:

100% Guiltin’ Free

Sample items:

Caesar Cardini Salad, Miso Chicken Bowl, Banh Mi Roll

Melt Shop

Units:

8

Menu mantra:

Next-Level Comfort Food

Sample items:

Maple Bacon Sandwich, Truffle Turkey Sandwich, Loaded Tots

Fields Good Chicken

Units:

1

Menu mantra:

Nourish Your Adventures

Sample items:

Bueno Bowl, Applewood Wrap, Good Karma Salad

How do you decide which brand goes into which market?

AS: They have unique growth strategies right now. Melt Shop has a particular initiative right now where it’s looking at several malls; we are working on the format of Melt Shop so that the customer frequency will be increased in urban environments. But we do feel like the one that probably has to go to A markets is The Little Beet, because that style of eating is still catching on in several markets, whereas in New York and on the West Coast, it’s commonplace. Filling in the middle of the country is going to take some time.

Fields, on the other hand, is built around the No. 1 protein sold in the U.S. It’s a very obvious and clear offering. Price-wise and also with the quality of the food, there’s a real ability to bring that across the country. That one has probably a higher potential to move into A and B markets faster than our other brands right now.

What kind of lessons did you learn from franchising that help you with your proprietary brands?

AS: So many. I think on the operations side in particular, it’s the ability to really understand the importance of systems, everything from this box of lettuce should take you X number of minutes to prep, which obviously then translates into productivity and scheduling needs, to ways that we’re looking at sourcing. Across the board I would say that the systems we’ve learned through the franchisors have been extremely helpful for these young brands.

JR: And all of them are obviously sensitive about their brands; Five Guys in particular taught us that you really have to control the brand. That requires very strict standards and adherence to policies and all of that stuff. Obviously every store represents the brand, so the look and feel, consistency, employees—the whole thing—is really important for us.

How do you leverage your people at Aurify?

AS: I think it’s one of our biggest strengths right now as a company: the opportunity to create a network effect where everybody is employed by Aurify Brands, even though they work for a particular brand. It gives us the opportunity to really look at each individual not as part of a particular brand, but as part of our overall company. That means a rising star at any brand can then go into a new brand or stay within their own. Whichever brand is growing the fastest has the largest need for filling gaps, and we’re able to promote people across brands right now, which is very powerful, because it shows people that there is true opportunity to move up and quickly, rather than waiting for their store GM to leave in order for everybody to move up the chain.

What kind of growth are you envisioning for the proprietary brands?

AS: We feel like we can be a billion-dollar company in the very near future. That’s what we’re keeping our eye on right now, is how we reach that with our proprietary brands.

JR: We have a strategic planning session for each of the brands, and we’re looking at 2016, obviously, but we also plan out for the next five years. We do that for each brand; it’s a very comprehensive exercise. We define goals that we are confident we can execute against, so things like the number of stores we can open in a given market for a given brand. On a brand-by-brand basis, nothing is overwhelming. Collectively, the numbers start to get big because it’s across four proprietary brands, but individually they’re reasonable to execute against.

What’s in the cards for franchising the proprietary brands? How do you feel about going from franchisee to franchisor?

AS: Melt Shop is the one contender for franchising right now. We’ve done most of the paperwork at this point, so really the decision to turn it on, right now, is ours. What we think we have an advantage on is we’ve been through multiple franchise systems and networks at this point. We know the good and bad. We learned a lot from each franchise and we learned how to police or not police your franchisees.

Not alienating your franchisees—being a better partner rather than just somebody who you’re paying a royalty to—makes a big difference. We’ve had the luxury of being through those systems and seeing it from enough sides that we know at this point what we love and don’t love from a franchisor. We can really bring that to bear in our own franchising capabilities. That all being said, being a franchisor is a totally different business from what we’re in right now. Fortunately, we’ve seen that side of the business, but we’re aware enough to know it’s very different, and it would be run as a totally separate business.