Inspire Brands’ September acquisition of Jimmy John’s was a headline grabber, no question. But was it surprising? Firstly, we only need to look at the structure to see the synergy. And, not to mention, CEO Paul Brown hinted this was coming months ago.

In 2013, Brown was hired by Roark Capital from Hilton Worldwide, where he spent five years. He’s drawn from that outsider experience ever since, building what’s now the country’s fourth-largest restaurant company at 11,200-plus units and $14 billion in annual system sales.

What’s made Inspire stand out from day one is how it mirrors Brown’s former hotel universe. Namely, the framework of driving concept value from within a multi-branded portfolio. Independent identities that pull from a center of excellence, as he told QSR last year.

Unlike some other restaurant holding companies, Inspire touts a focused, integrated model. Each brand relies on the resources of the other. Leveraging collective strengths like HR, finance, legal, IT, development, communications, customer personalization and insight, and media. It’s akin to how hotel organizations spread out like a web from a base of power.

When Roark formed Inspire in February 2018 following Arby’s $2.9 billion Buffalo Wild Wings blockbuster, Brown told The Wall Street Journal that Inspire wanted to create a restaurant company “with a broad portfolio of distinct brands across a full spectrum of restaurant occasions.” One that capitalizes on the benefits of scale not just to save cost, but also to enable outside investments in long-term growth initiatives.

Another way to look at it: Acquire brands that capture more visits from the same customers by establishing a portfolio that keeps guests engaged across all dayparts, price points, and interest levels. Imagine a customer who goes to Arby’s for lunch, Buffalo Wild Wings for dinner, and Sonic Drive-In for a night-cap. That’s a different path than many competitors who stay and live within a certain segment, although they do cross occasions. Darden, Brinker International, and Bloomin’ Brands, for example, operate chains amid different full-service distinctions, like fine dining and casual. Yum! Brands, the owner of Taco Bell, KFC, and Pizza Hut, sticks to fast food, as does Restaurant Brands International with Burger King, Tim Hortons, and Popeyes.

Brown told QSR earlier that brands added to the Inspire system could be quick service or casual, franchised or corporate, national or regional. They just need to be unique to the market and have runway to grow.

This is essential to unlocking where Inspire is headed, why Jimmy John’s made sense, and who could be next. Brown told the WSJ he envisioned buying no more than 10 chains, but with systemwide sales between $1 billion–$4.5 billion each. There are quite a few big hitters left that fit the bill.

“If you think about the framework around how you approach a brand and how you approach executing on that, in many ways it’s very similar, right?” Brown said to QSR. “Yes, one brand has a different service model than the other. But at the core … whether it be culinary, whether it be labor scheduling, whether it be marketing, all those core skill sets are fundamentally similar. And we can learn from each other.”

Jimmy John’s deal had a unique twist to it simply because Roark bought a majority stake in 2016. At the time, the sandwich brand was valued at roughly $2.3 billion when Roark’s stake included a minority share in the brand owned by private-equity firm Weston Presidio.

By acquiring Jimmy John’s (for an undisclosed amount) the company essentially transferred the business from one Roark entity to another. The chain changed hands but ultimately remained under the control of Roark.

At the end of 2018, 2,748 of Jimmy John’s 2,803 restaurants were franchised. That likely appeals to Roark as well, which has investments in Carvel, Auntie Anne’s, and Carl’s Jr. The company led Wingstop Inc. to a public offering in 2015 after owning a majority for five years. It paid $200 million for Jamba in 2018 (now FOCUS Brands run).

Roark founder Neal Aronson co-founded US Franchise Systems, a hotel brands operator, before taking the private-equity route as well.

And just generally speaking, private equity and fast food have been on a tear in 2019, and the dynamic is ripe for Inspire to pounce. In the first nine months of the year, per PitchBook, private-equity deal value in the sector approached $5.35 billion. In all of 2012, it was just $3.17 billion.

Some experts have credited this surge for the industry’s current traffic problems. Restaurants, according to data cited by the WSJ, are growing at twice the rate of the population. Investors are partly to blame. Since the early 2000s, banks, private-equity firms, and other financial-backed powers have poured billions into the food industry. The reason being that restaurants are considered by many investors to be more tangible than dot-com start-ups. PE firms have also seen success in taking public restaurant companies private, as a rash of M&A activity recently suggests.

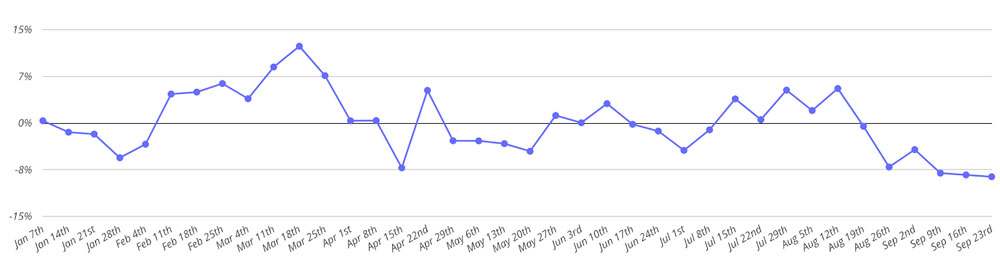

And just look at the capital difference three years makes as proof.

The consolidation of the industry is one way restaurants are guarding against the challenges afoot. Everything from rising labor costs to uncertain commodities to regulations. Smaller brands face added challenges in a rapidly moving industry, Christian Charnaux, Inspire’s chief growth explained to QSR previously. They often need to expand rapidly to satisfy customers’ needs, whether that be technology, convenience, accessibility, and so forth. A portfolio of concepts, however, can serve customers in multiple ways across multiple touchpoints if approached correctly. It also allows for forward thinking—testing, learning, and implementing tech on the consumer and operational front—instead of making day-to-day, bottom-line, survival-mode decisions.

Today, 10 companies control more than 50 restaurant brands (Brinker, Yum!, RBI, Bloomin’ Brands, Golden Gate Capital, Roark Capital, JAB, Darden, Jollibee Foods Corp, and Sun Capital).

Houston billionaire Tilman Fertitta’s Landry’s has been on a buying spree lately, scooping up Del Frisco’s Double Eagle Steakhouse and Grille and buying Restaurants Unlimited out of bankruptcy. So has L Catterton, which took over bartaco and Barcelona Wine Bar.

Like many of these entities, Inspire is pushing its chips all-in on scale, and the ability to leverage a collection of brands to better serve its locations and franchisees—something doubly important in a data-driven age. Customer insights, operational analytics, development analytics—these are shared services that help each individual concept in Inspire’s portfolio, Brown said.

Chains like Buffalo Wild Wings pull marketing and operational efficiencies from Arby’s, and so on. And they collectively purchase better media and negotiate friendlier contracts with suppliers in existing markets.

In the case of Jimmy John’s, can its delivery prowess ignite across Inspire’s vast footprint? Few restaurants at this scale, in any segment, have nurtured in-house delivery like Jimmy John’s, which uses zones to make sure it’s serving areas within five minutes of each restaurant. The company has empathically resisted the pull of third-party services over the last couple of years. Jimmy John’s started delivering in 1983 (when it opened) and employs some 45,000 drivers.

That’s delivery knowledge Inspire will harness company-wide during a time when the service is disrupting every corner of the industry. And the company said the ideal will flow both ways. When it bought Jimmy John’s, it noted, “Inspire will provide Jimmy John’s with greater capabilities in areas like product innovation, brand marketing, and new restaurant development, as well as stronger purchasing scale in areas like supply chain and media buying.” The company added Jimmy Johns would “benefit from Inspire’s technology investments and integrated data and analytics platform.”

Financially, Jimmy John’s is an easy sell. It’s one of the fastest-growing chains in the U.S. The brand had system sales of $780 million in 2010. By 2018, it hit $2.1 billion, or 174 percent growth. There were 1,130 restaurants nine years ago, marking 148 percent growth to last year’s 2,803 locations.

Jimmy John’s was the fourth largest sandwich chain in America at the end of 2018 in terms of U.S. systemwide sales (in millions), according to the QSR 50. It trailed just Subway ($10,410.34), Panera Bread (5,734.63), and Arby’s ($3,886.90). Jimmy John’s came in at $2,200.00. Jersey Mike’s was next at $1,148.48. Jimmy John’s added 48 restaurants in 2018 from 2017.

So, now Inspire runs two the four largest sandwich brands in America. And that runway Brown spoke of? There’s no end in sight.

Looking deeper

Silicon Valley foot traffic analytics platform Placer.ai dove into some location data to measure Jimmy John’s performance, and circle where some whitespace might still lie.

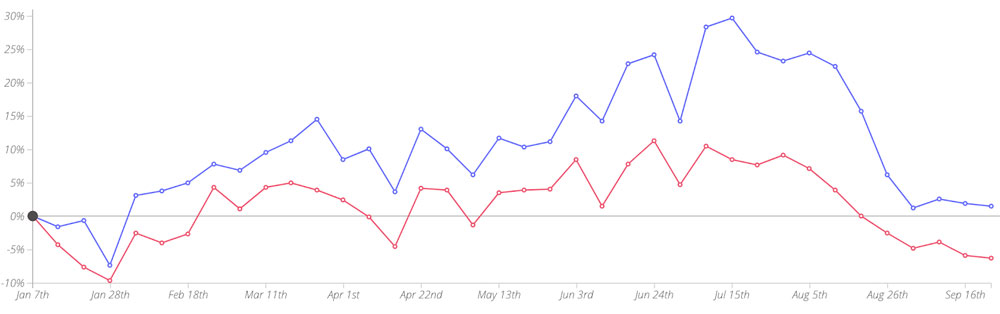

Below is a graph of Jimmy John’s in 2019 compared to Subway (red). Although the chains exhibit similar overall growth trends, Jimmy John’s shows higher baseline growth relative to January 2019. While higher relative growth is expected for a smaller brand (Subway had 24,798 domestic restaurants last year and sees more than 10 times the traffic of Jimmy John’s), it’s still a key indicator of the chain’s potential.

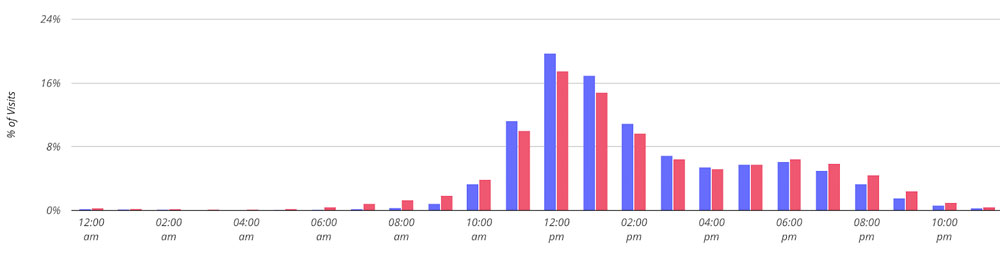

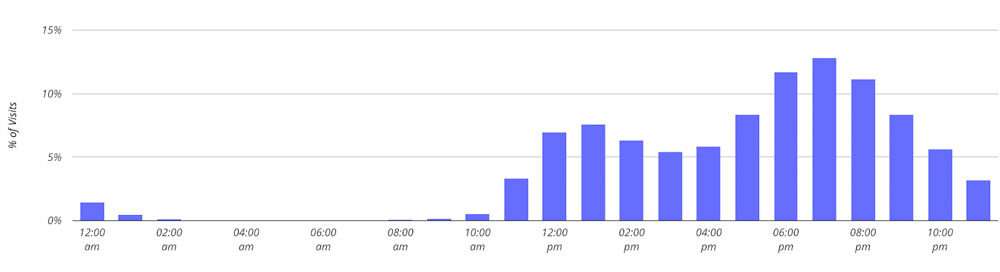

“Whenever you see an industry leader like Inspire make an acquisition, the question that immediately arises is why?” says Ethan Chernofsky, VP of Marketing at Placer.ai. “In this case, looking into Jimmy John’s data presents a powerful picture of a brand with proven growth that still has untapped potential. The heavy focus of strength around lunchtime means that strong visit numbers could still be expanded with better dinner offerings. This capacity to increase strength on a per-store basis is incredibly powerful and should make the brand particularly exciting to watch.”

In this breakdown, it’s clear (and understandable) that Jimmy John’s and Subway see the majority of their traffic during afternoon hours. Nearly 50 percent (47.7 percent) of all Jimmy John’s visits occur between noon and 3 p.m., per this data set.

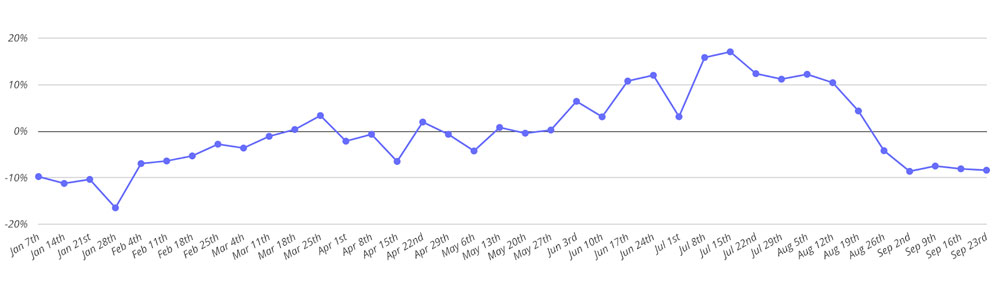

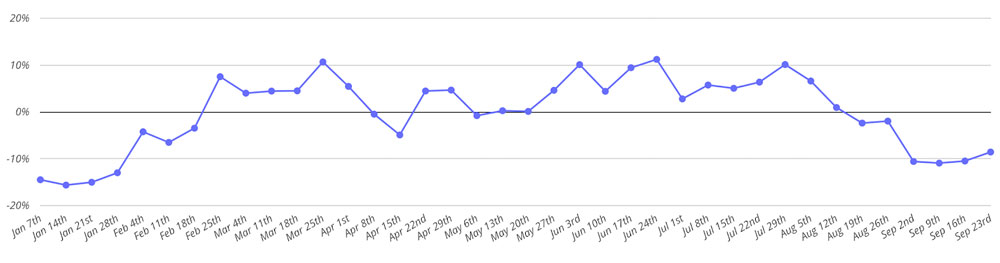

Speaking to Brown’s point, Inspire’s portfolio has daypart and seasonal variety.

Jimmy John’s surges in the summer.

Arby’s preforms strong late winter to early spring, with a similarly robust summer season.

Buffalo Wild Wings, though, peaks mid-winter to early spring with a heavy drop in mid-spring and a slight pick-up in the summer months. All dip toward the start of fall 2019, which is relatively common for restaurants as people get back into daily routines and eat more at home.

And being a full-service brand, Buffalo Wild Wings’ strength lies in the evening hours, with 44.1 percent of visits taking place from 6–10 p.m.

The lasting impression here is that Jimmy John’s has plenty of innovation ahead. It’s been growing in one of the industry’s heaviest categories, but daypart and delivery potential clears space for future growth.

“Jimmy John’s ability to manage seasonal drops, and to continue to own the daytime peaks while maximizing evening hour potential will certainly affect its long-term success,” Placer.ai said.