The pandemic has reshaped the restaurant industry. Tens of thousands of eateries have closed, with the majority being in the overlapping universes of full-service and independent restaurants. However, as bad as things were at the outset, bright spots emerged in a matter of weeks. The advantages held by quick-service restaurants and pizza are easily understood, as are the obstacles faced by full-service restaurants.

But what of the fast-casual segment? How did the pandemic help or hurt the brands that are often proud of being classified as a fast casual? And what might they expect in the post-pandemic world?

To understand the impact of COVID-19 on the fast-casual universe, it is important to visit one of the foundational elements for the creation of the segment: Real estate.

Prior to the emergence of fast-casual brands, the restaurant industry was a simpler marketplace. Heading into the 1990s, the primary industry segments were fast food, buffets, pizza, and the various forms of full-service dining. In those days, starting a new restaurant concept was an expensive proposition. Conventional wisdom demanded at least a 2-to-1 sales-to-investment ratio. Add up the cost of dirt, building, and FF&E, and you were staring at a capital requirement easily exceeding $1 million. Faced with the prospect of competing against the mega-brands that dominated quick service, launching a new restaurant with an expectation of hitting north of $2 million in sales was a risky proposition. Prior to the 1990s, some tried and failed. (Remember D’Lites?)

Restaurateurs seeking to launch innovative concepts were in a quandary. The business environment demanded innovation. Many aspiring restaurateurs turned to in-line, leased real estate, which could be developed more affordably. It was increasingly fertile ground for fast-growing pizza concepts and sandwich brands. It was about to become the incubator for what would later be coined “fast casual.”

But how could a fledgling restaurant compete on the one hand against the convenience, street visibility, and benefits of scale possessed by the fast-food giants, and on the other hand rival full-service restaurants? To overcome the convenience and price advantage held by quick-serve rivals, the new restaurant had to offer an experience superior in quality, hospitality, and ambiance. But that was just half of the formula. To win over the casual-dining patron, the food had to rival the quality, and at a better price. And if casual-dining-quality food could be served faster—not as fast as quick-service restaurants, but faster than a full-service experience—then the new restaurant concept stood a chance of drawing enough volume from both segments to make a go of it.

It was a formula that promised the best both worlds. And it worked. Chipotle and Panera were two of the most prominent innovators, but by the turn of the century, the ranks swelled with other start-ups and converts, and their collective success led to the labeling of the category. To this day, the tell-tale characteristics of a fast-casual restaurant remain well-known, but the genesis of the category—the need for reduced capital outlay and affordable real estate—has been long forgotten or overlooked.

Of what consequence to the fast-casual segment is this evolutionary tale? I’ll come back to that in a moment, but first, let’s examine how the fast-casual segment fared during the pandemic. Has the established formula for fast casual served all brands equally during the past 13 months?

Fast-casual brands that featured products that held up well when purchased for off-premises consumption were able to gain a leg up during the darkest days of the pandemic. No matter the cuisine, fast-casual brands that embraced off-premises tactics such as online ordering, curbside pick-up, and third-party delivery prior to the pandemic were ahead of the game. If surviving the pandemic was akin to running a marathon among fast-casual restaurant rivals, brands with strong off-premises attributes were starting the race 13.2 miles from the finish line.

But what about the post-pandemic business environment?

The use of restaurants by the American consumer was evolving well in advance of the pandemic. The reasons are many and complicated. But the net result was a shift in behavior in the direction of off-premises consumption. Brands were already adjusting, and Firehouse Subs serves as an example. Eight years ago, dine-in occasions accounted for more than 50 percent of our business. At the start of 2020, dine-in was down to 37 percent. We responded along the way with improved packaging, online ordering, and in more recent years, embracing third-party delivery. I was known on occasion to facetiously suggest that our dine-in sales would never go down to zero. But on March 16, 2020, that is exactly what happened.

Many pundits agree that the pandemic has hastened changes in consumer behavior that might have otherwise taken several years to unfold. This is a very important consideration for the future of the fast-casual segment. Had the pandemic not occurred, the decline in dine-in business would have continued. Perhaps brands would have had time to evolve in tandem with a more gradual change in consumer behavior. But due to the pandemic, customers were virtually forced into the trial of a brand’s off-premises experience. The brands that passed the test are now in the consideration set for off-premises occasions; occasions that will continue to be the dominant area of growth for the industry in the post-pandemic world. Long-term, if there are winners or losers within the fast-casual segment, a defining characteristic will be their ability to meet and exceed the expectations of guests that enjoy their food outside of the restaurant.

This brings us back to real estate. The economic fundamentals are still akin to that of the 1990s. The post-pandemic regeneration of the restaurant industry may well sprout from the fertile ground that gave birth to fast casual, creating a renaissance in restaurant development for the segment. Some brands will lean into free-standing buildings, and drive thrus will be coveted. The line will increasingly blur between quick service and fast casual. But the economics have not changed all that much, and it is in the realm of leased in-line space where the current white space will likely be filled. Of all the segments, fast casual is best positioned to fill the void created by the pandemic. It will be an exciting time.

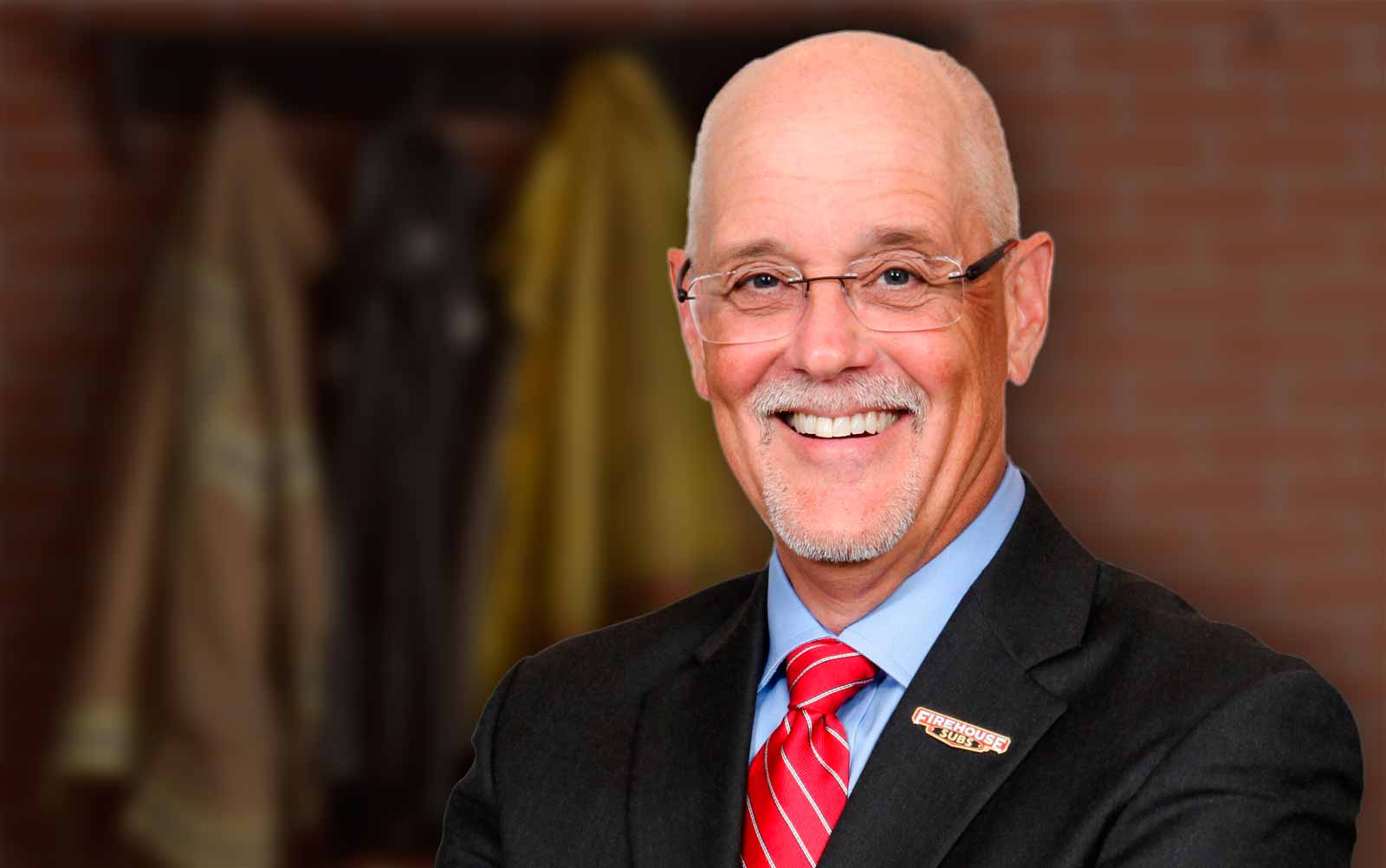

Don Fox is Chief Executive Officer of Firehouse of America, LLC, in which he leads the strategic growth of Firehouse Subs, one of America’s leading fast casual restaurant brands. Under his leadership, the brand has grown to more than 1,190 restaurants in 46 states, Puerto Rico, Canada, and non-traditional locations. Don sits on various boards of influence in the business and non-profit communities, and is a respected speaker, commentator and published author. In 2013, he received the prestigious Silver Plate Award from the International Food Manufacturers Association (IFMA).