As announcer Eric Collins introduced Michigan State’s players during a basketball broadcast on the Big Ten Network in December, he paused to give special mention to Branden Dawson, a freshman from Gary, Indiana: “Dawson, the McDonald’s All-American.” It had very little to do with Big Macs and everything to do with big-time basketball.

For McDonald’s, which attached its name to the country’s most prestigious high-school all-star game more than three decades ago, such mentions have become commonplace. The term has become ubiquitous in the basketball world, shorthand for the best high-school players in the country and the source of untold visibility in the sports world for the equally ubiquitous restaurant company.

Being selected for the McDonald’s All-American Games—a women’s game was added 10 years ago—is the highest honor for high-school basketball players. There are other All-America teams, but no other nationally televised all-star game. Players yearn for the recognition, college coaches covet those players, and fans eagerly track their college choices.

“It’s an indication that a kid has achieved success at the scholastic level,” says ESPN commentator Dick Vitale. “It doesn’t guarantee success at the collegiate level. But it’s very prestigious, and we refer to kids as a McDonald’s All-American, or he won the McDonald’s Slam Dunk contest. It’s very prestigious, and many of these kids become successful.”

McDonald’s, meanwhile, benefits from having its name inexorably linked with the top basketball talent in the country, increasing its visibility with the pre-teen and teen demographics, as well as with sports fans in general. Starting with the first class in 1977, which included future Hall of Fame player Magic Johnson, McDonald’s has injected its name into the game of basketball worldwide in a very real way.

For McDonald’s, it’s about more than marketing. The company isn’t a sponsor of the game; it owns it. The game has been held all over the country, from San Diego to New York, from Colorado Springs to Coral Gables. When this spring’s event is held in Chicago for the second straight year, it will be the first time the game has been held in the same location twice.

“The primary beneficiary, without question, is the Ronald McDonald House Charities,” says Douglas Freeland, the director of the McDonald’s All-American Games and a McDonald’s marketing executive. “From the very beginning, the proceeds from the game have benefited Ronald McDonald House to help families that are in need. McDonald’s has a long tradition of involvement with sports, whether it’s the Olympic sponsorships or professional sports. The McDonald’s All-American Games are a very important asset.”

What became a national program began locally, in the early 1970s, as a showcase for Washington, D.C., and Baltimore’s top high-school players. In 1977, the organizer of the game, a promoter named Bob Geoghan, came to McDonald’s with the idea of pitting a local all-star team against some of the country’s best college-bound players.

Looking back, Al Golin never could have imagined the impact McDonald’s association with the game would have. Golin, the founder of PR giant GolinHarris, has worked with McDonald’s since 1957. He loved the potential exposure in each player’s individual market when he was selected and the way it fit with the larger goals McDonald’s set for community involvement.

“First of all, McDonald’s is always interested in young people, saluting young people,” Golin says. “It involved a lot of inner-city young people and minority people, which is always a consideration for McDonald’s. More than rewarding people for their basketball skills, it was about trying to teach a little about life and life after basketball. There’s always a banquet, with a sports figure, and the message is that there’s life after basketball, and you have to prepare for it. The message was always the key one for McDonald’s.”

After the first game was a success, McDonald’s decided to take the program to the national level. In 1978, two teams of all-stars from across the country played each other in Philadelphia. In the years since, the game, and its accompanying slam-dunk and long-range shooting contests, has been held all over the country, in massive NBA arenas and historic college gyms alike.

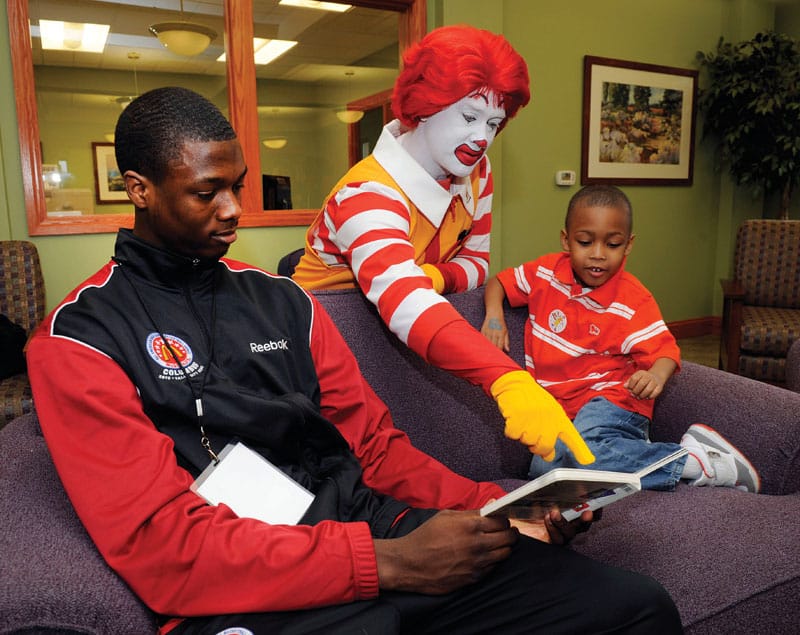

Since 1989, the game has been carried on national television. This month it airs on ESPN, which also carried the live announcement of this year’s team in February. The money raised each year goes to the Ronald McDonald House in the host city, and players visit hospital patients and their families as part of the festivities.

“The McDonald’s All-American Game is unique in that it is a celebration of young people that shows them the value of giving back,” Freeland says. “We take all the players to the Ronald McDonald House on game week. It’s quite an experience with these families. It reinforces with these players, who are very gifted, the value of giving back.”

Because the McDonald’s All-American Games feature high-school athletes, the company’s involvement has raised concerns from Michael Jacobson, head of the Center for Science in the Public Interest, that McDonald’s is using athletics to promote “generally unhealthy food.”

Freeland says such criticisms are “completely misinformed,” citing the game’s charitable purpose and community-service endeavors.

“We don’t need to use the McDonald’s All-American Games to soft-sell anything,” Freeland says. “Any resources devoted from a marketing or PR standpoint to the McDonald’s All-American Games are in terms of driving ticket sales, driving viewership of the game on TV, or reinforcing the linkage to Ronald McDonald House Charities.”

From a more practical standpoint, Carter, the USC sports business professor, says McDonald’s recent changes to create more healthy menu choices were beneficial if the company was going to continue to remain closely associated with basketball.

[pagebreak]

“The fact that they’ve tweaked their menu over the last several years to become more health-conscious enables them to maintain that ubiquity,” Carter says. “It would have been a little bit more of a challenge for McDonald’s to remain as relevant, given the great concern about childhood obesity, without making changes. That’s allowed that connection to sports to remain totally relevant.”

Among sports sponsorships and marketing programs, the name of the company and the honor of being on the team are inseparable in a way that few similar linkages can attain. NASCAR’s Winston Cup, now the Sprint Cup, achieved that status, while the college football bowl games that have ditched traditional names aspire to it: Atlanta’s Peach Bowl is now the Chick-fil-A Bowl, an attempt to build the kind of brand recognition McDonald’s gets from basketball.

“How long have they had that relationship? It’s been years,” says David Carter, the executive director of the Sports Business Institute at the University of Southern California. “The Heisman Trophy has been presented by how many people—Nissan, Aflac, whoever—over the years? The continuity and the relevance add to McDonald’s being ingrained as part of the nomenclature.”

McDonald’s involvement with high-school athletics fits with the company’s larger vision. Golin, the PR pioneer, coined the term “trust bank” to describe programs designed to generate goodwill for McDonald’s. McDonald’s once sponsored an All-American marching band that performed in the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade and the Tournament of Roses. Golin says that program was abandoned when it became too logistically complicated. The basketball program proved far simpler—and more effective.

“It became such a status symbol for young people in athletics. We certainly never envisioned it would catch on that well,” Golin says. “It’s become such an iconic program, very good for the company associated with it.”

McDonald’s success in basketball has spawned other marketing programs targeting high-school athletes. In 1985, Gatorade began honoring a male and female high-school athlete in each of the 50 states and the District of Columbia, as well as sport-specific winners in 12 sports. The program names national winners in each sport, as well as two national athletes of the year.

In 1994, Wendy’s and the foundation that awards the Heisman Trophy collaborated to form the High School Heisman program, which honors excellence in athletics, academics, and community service. This year, a male and female winner were chosen among 10 finalists out of more than 48,000 applicants.

As truly exceptional high-school players, McDonald’s All-Americans can change the course of a college basketball program—or a career. Since the first team was named, a McDonald’s All-American has been on the roster of all but one men’s NCAA championship team.

In 35 years, 495 McDonald’s All-Americans have gone on to the NBA, and this year, McDonald’s will honor 35 all-time All-Americans, in honor of the game’s 35th anniversary. The event spans generations: Doc Rivers, the coach of the Boston Celtics, was a McDonald’s All-American in 1980. Last spring, his son Austin became the second generation of the family to receive the honor.

“It’s awesome to meet other players that are in the same position, guys who have all done something great, no matter where they’re from, and we all have a certain amount of respect for each other,” says Austin Rivers, who is from Winter Park, Florida. “It’s neat, because we all want to play against each other. We never talk about it, but in the back of our minds, we all want to prove we’re better than one another.”

The vast majority choose to attend some of the biggest programs in men’s college basketball: Duke, Kansas, Kentucky, North Carolina, and so on. It’s the kind of talent that keeps those programs on top. Ray McCallum, the basketball coach at the University of Detroit, normally doesn’t have a chance at that kind of player. Two years ago, he found one under his own roof.

His son, Ray Michael McCallum, was named a McDonald’s All-American and attracted national attention. In the end, he chose to stay at home and play for his father. Ticket sales and sponsorships both increased after Ray Michael made his decision, as did the interest of television networks.

“With his name recognition, he’s recognized as a marquee player,” the elder McCallum says. “The program, the first year we came here, had maybe three or four games on TV. Now, we’re looking at 15.”

They’re Lovin’ It

The McDonald’s All-American alumni list includes the NBA’s biggest stars and more than 30 men’s NCAA Championship players. Here is just a sample.

Earvin “Magic” Johnson, 1977

Isiah Thomas, 1979

Michael Jordan, 1981

Patrick Ewing, 1981

Shaquille O’Neal, 1989

Kevin Garnett, 1995

Kobe Bryant, 1996

LeBron James, 2003

Dwight Howard, 2004

While the power of a McDonald’s All-American is remaking that program, a McDonald’s All-American played a big role in the progression of Mark Fox’s coaching career. Now the head coach at the University of Georgia, the 43-year-old Fox was already winning at Nevada when he fought off Ohio State to keep Luke Babbitt, a McDonald’s All-American from Reno, at home. Babbitt now plays for the NBA’s Portland Trail Blazers.

One year later, Fox’s proven ability to recruit McDonald’s All-Americans helped him land the job at Georgia. During his second season there, Fox recruited another McDonald’s All-American, Kentavious Caldwell-Pope, the first McDonald’s All-American to play at Georgia in 12 years.

“For any coach, as you look at jobs, people are going to ask whether you can recruit or not,” Fox says. “The best way to answer that question is to land a McDonald’s All-American. Those guys are hard to get, especially at a school of Nevada’s size. That helps as schools look at you.”

Within the game of basketball, the McDonald’s All-American Games couldn’t be more relevant. For an 18-year-old basketball player, there is no higher badge of honor.

“It’s crazy,” says Austin Rivers, a freshman at Duke. “You look at the list, you have people like Magic Johnson, people like Derrick Rose, and LeBron [James]. Pretty much every NBA All-Star has most likely been in the McDonald’s All-American Game. Any time you get to be a part of something like that, it’s amazing.”