Omicron’s impact on restaurants was significant, but it doesn’t appear to be lingering like past surges. Just take The Cheesecake Factory, whose Q4 sales were 10.6 percent ahead of 2019 as the third week of December approached. Once the quarter ended on December 28, the casual chain’s comps dipped to 7.7 percent, and it also paid $3.8 million of incremental costs related to COVID sick time.

In a departure from previous plunges, though, especially in the early pandemic window, staffing proved a battle of attrition more than an effort to predict traffic. Employees weren’t furloughed due to broad dine-in closures; rather they had to quarantine or call out sick as Omicron stampeded across the country. In turn, Cheesecake Factory’s ensuing Q1 sales through February 15 soared 24.3 percent over the prior year as hiring levels in January rose 10–15 percent compared to Q4.

Starbucks mirrored this movement, too. It posted a record holiday quarter before the variant pulsed in the last two to three weeks of Q1, which ended January 3. Customer mobility declined, call-outs, as mentioned, surged, and Starbucks opened the coffers for COVID pay. In all, Starbucks said Omicron would drag margins by roughly 200 basis points.

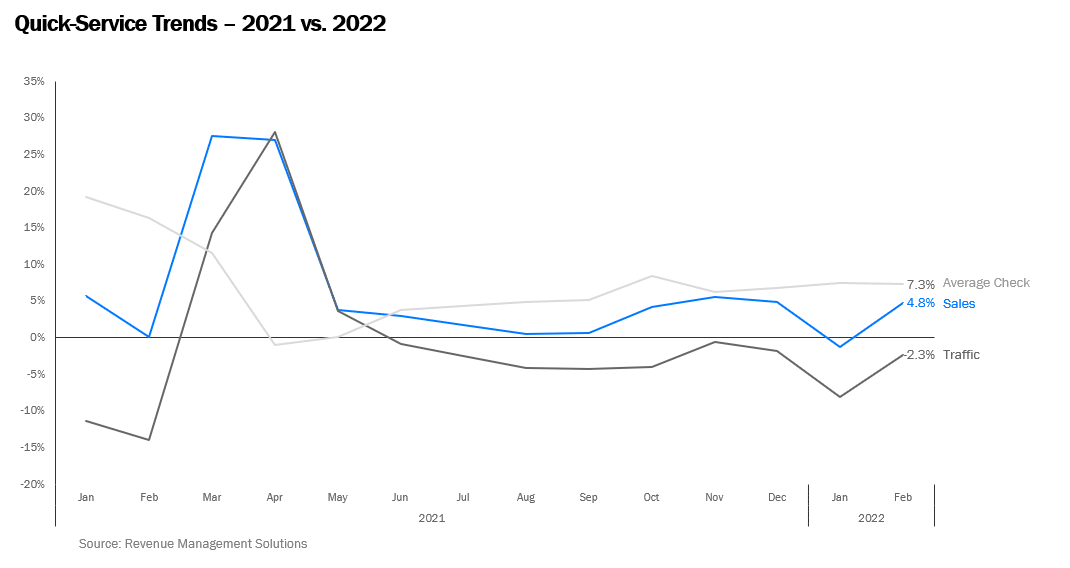

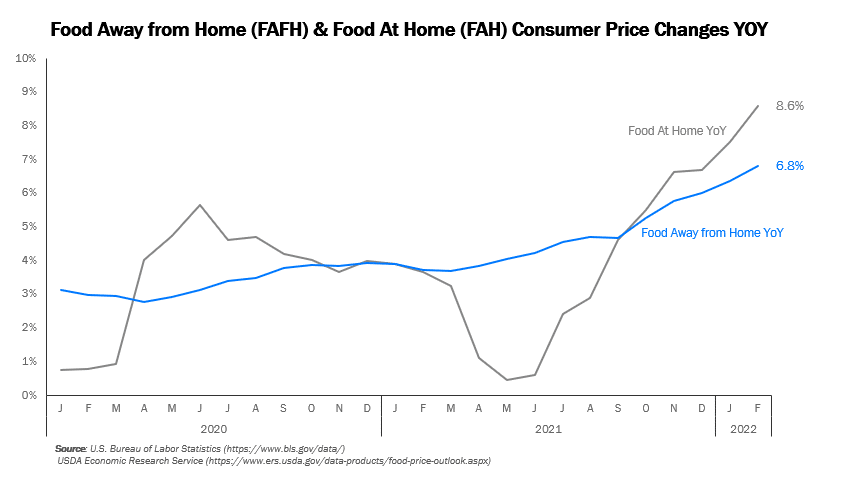

However, recent signs suggest the industry’s Omicron panic is over. Revenue Management Solutions data in February showed quick-service restaurant sales up 4.8 percent, year-over-year, after a 0.8 percent drop in January. Traffic declined 2.3 percent, yet made a 5-point jump back to centerline from the previous month, when it was negative 7.7 percent. Average check hiked 7.3 percent versus 2020’s comparable stretch—a sure reflection of rising prices. The food away from home index rose 6.8 percent over last year, which represented the largest 12-month increase since December 1981. Limited-service meals increased 8 percent, year-over-year, while full-service menu prices grew 7.5 percent.

RMS said February’s results indicate consumers are regaining confidence as cases relax and restrictions lift—a rebound cycle that’s repeated itself throughout the past two-plus years: the so-called “pent-up demand” central to the industry’s recovery. Or, as soon-to-retire Starbucks CEO Kevin Johnson said in February, “For over two years now, and thanks to our partners [employees], our business has emerged stronger after each wave of a COVID surge has peaked, and we expect this will be the case as Omicron runs its course.”

“Furthermore,” RMS added, “it appears that the drop in January’s performance was due to external factors, likely the rise in cases due to the Omicron variant, rather than a systemic shift in consumer demand.”

It’s a familiar COVID tale—restaurants weathering regulatory and macroeconomic hurdles when it comes to driving business, not necessarily downturns in guest preference.

On the pricing note, RMS said, “now is the time for [quick-service restaurants] to communicate value meals, bundles, and specials that outweigh the cost of cooking at home.” Just as sector prices climbed, the same was true in grocery (up 8.8 percent, year-over-year, the largest 12-month increase since April 1981).

“Consumer habits are fundamentally different,” RMS Director of Research and Consumer Analytics Francois Acerra said in an analysis of last year’s trends. “Traffic is down, but the relative increases in average check indicate that [quick-serves] haven’t lost customer segments. Instead, we believe that quick-service restaurant customers have permanently changed their behaviors—visiting less frequently than pre-pandemic yet spending more per visit.”

It’s not all about price, either.

“Given the intense pressure on margins caused by rising commodity prices and labor shortages, analysts may give credit to price increases for the overall rise in average check,” Acerra added. “But when we dug deeper into the numbers, it’s clear that a behavior change is also driving up average check. In short, consumers are ordering more food, and for larger parties. We’ve noticed that the increase in basket size is partly due to more guests being on the same check and that, in fact, the share of single-party orders has declined.”

Last year, the quantity per transaction was up 14.3 percent compared to 2019, RMS reported. Compared to average net price, which was 7.5 percent higher, “and it’s clear that net sales performance was sustained by average check growth,” the company noted.

RMS conducted a November survey of more than 800 restaurant consumers. Seventy-six percent said they were going to the drive-thru at least once a week compared to 63 percent for dining in. Delivery peaked in 2020 and has settled since (from 60 percent in November 2020 to 49 percent this past November).

“Wait times, poor customer service and order inaccuracy—not price—are being cited in our surveys as the top reasons for dissatisfaction,” Acerra said. “[Quick-serves] that can overcome challenges and deliver meals quickly, accurately, and with a smile will deliver value to customers and potentially outweigh necessary price increases.”

The company also fielded data from north of 8,000 diners to check on digital adoption and where it’s taking the industry. Nearly half of respondents said they’d download a restaurant app to earn loyalty rewards and 39 percent said they’d do so for a deal or a promotion. “With app adoption growing—36 percent of respondents have five or more [quick-service restaurant] apps installed—[quick-service] brands should focus on loyalty rewards and app-exclusive promotions to stand out from the competition,” the company said.

In addition, 43 percent of respondents said they believe it’s “better” or “much better” than ordering in-person. And yet there’s room to separate. Nearly one in four respondents reported not being able to customize or make substitutions, receiving an incorrect order, or not being able to order wanted items. The first two issues presented the biggest consequences—nearly one in three people said they stopped using an app after experiencing either.

According to Oracle Food and Beverage’s “Restaurant Trends for 2022” study, 34 percent of consumers felt online and delivery orders were being prioritized over in-person guests. Forty-seven percent added in-person orders were taking “significantly” longer than order-ahead and drive-thru customers.

While it’s clear digital adoption rode the COVID tailwind, what happens now within loyalty/rewards might just present the next frontier of fast-food value. In Paytronix’s 2022 Restaurant Friction Index, research showed 96 percent of restaurant managers marked down prices for loyalty program members. The average loyalty discount was roughly 3.8 percent.

Overall, restaurants charged an average of 24 percent more for menu items listed on aggregators than their own websites. Quick-serves were the most likely to bump up third-party prices, with 27 percent of managers confirming they sell the same foods for higher prices. Just 14 percent of table-service restaurant managers noted the same.

Black Box Intelligence’s March 16 report noted restaurants posted positive sales growth for the third consecutive week, and the strongest growth since the week before Thanksgiving (excluding the Valentine’s Day period). Although guest counts remain under pre-pandemic levels, traffic improved more than sales compared to the previous week, Black Box said.

Breakfast was the daypart with the highest sales growth during the week, followed by mid-afternoon and dinner. Lunch and late-night continue to lag.

Staffing remains a roadblock to capturing upcoming pent-up demand as well. As of January, restaurants were operating in each of their locations with fewer hourly staff than they did pre-pandemic, in 2019, per Black Box.

Drops in staffing levels, however, remain lower for limited-service brands, with the median brand operating restaurants with 4.4 percent fewer hourly crew members per unit than two years ago. This translated into one less hourly employee per restaurant.

FAST FOOD INTO THE FUTURE:

Shake Shack is Piloting Bitcoin Rewards

The Restaurant Franchising Industry is Nearly Fully Recovered

Why the Pandemic Only Made Fast Casual Stronger

What’s Next for Restaurant Delivery?

Taking Stock of the Restaurant Industry’s Supply Chain Crisis

Restaurants, Meet the ‘Multiplatform Consumer’

Restaurants After COVID: An Industry for the Better?

Some of this movement owes to a shift from hourly to management employees that’s taking shape as retention inches ahead of recruitment on the priority list. The median limited-service brand increased the number of managers per location by about 0.5 during the same period, according to Black Box. “This can be a result of assigning some additional managers to some of their locations or relying on a larger number of part-time managers to cover the management duties,” the company said.

For full-serves, staffing declines are taking place across the board, with front-of-house hourly employees affected most. The median brand operated its locations with about 11 percent less front-of-house hourly employees than they did pre-COVID. In the case of back-of-house hourly employees, the reduction was about 6 percent, while the fall in average number of managers was higher.

From January 1 through March 20, labor platform Landed saw a 50 percent percent increase in job applicants as compared to the same period in 2020. “That’s the biggest jump we’ve seen since launching Landed in early 2020, and it shows a huge increase in active job seekers,” founder and CEO Vivian Wang said in an email.

Based on nearly 40,000 interviews, Landed data from the period showed a 74 percent quarter-over-quarter increase in job matching within the app (the rate at which applicants that fit the hiring criteria are matched to employer job openings), indicating more qualified candidates are entering or re-entering the job market.

So there is some proof restaurants are filling open positions more quickly.

“We’re encouraged by these job seeker numbers, as a few factors may be coming into play, including the reduction in unemployment benefits nationwide, COVID-19 numbers coming down, and cost of living increases, spurring candidates back into the job market,” Wang added. “Candidates will be job shopping for the best opportunities, especially with the rise of gig economy jobs like Uber and Lyft, not job hunting, so in order to stay relevant in today’s restaurant hiring world, it’s important that employers streamline and deliver a personalized hiring process for candidates.”

In sum, the current landscape provides plenty of transactions to chase for restaurants—inside and outside the four walls. But the path there is hardly narrow.

QSR caught up with Alec Haesler, director at Carl Marks Advisors, who has been working with restaurants of all sizes for decades, to discuss the state of the industry as spring approaches.

Let’s start with inflation. The story today, as we continue to hear, is higher prices, with a willing consumer. Is it inevitable, in your view, pushback will eventually begin to show in the form of traffic declines? Has that started to happen already, especially with gas prices now hitting diners’ wallets?

We are starting to see margin compression, as labor and inflationary pressures outstrip the ability for operators to pass through costs to end-consumers. February foot traffic comps were positive, especially as demand recovered from Omicron and municipalities start to repeal mask and vaccine requirements. That being said, March foot traffic is starting to show pockets of weakness.

I think we are going to see a persistent and significant inflationary environment in the coming months—especially for restaurant operators. Rising oil prices will increase both delivery costs and the cost of packaging and supplies. The crisis in Ukraine is driving up the price of corn and wheat, while Russia is a major exporter of ammonia for fertilizer. This all means a continued increase in input costs for the restaurant industry. Not to mention the current state of the labor market and what that is doing to average hourly wages.

At the same time, government stimulus has dried up, and consumers will start to feel the impact of inflation in their wallets. This likely means a pullback in consumer discretionary spending, less willingness to support increased check prices, and weaker foot traffic comps in the near-term. While foot traffic comps look positive today and people are optimistic about, “getting back out there”—I think we are going to see some regression in the coming months.

Generally, the idea is once prices go up, they don’t come back down. Is it possible we see an exception here? Or is this a “new normal” part of the dining out experience going forward?

Generally, prices rise much faster at the beginning of an inflationary cycle than they decline on the back-end. Operators that experienced margin compression in previous periods are going to take some additional profit to offset past losses.

Given the size and pace of inflation, as well as the non-recurring nature of some of the drivers, I don’t believe this is a “new normal” situation. It will, however, be something that takes a long time to work its way through the system before things stabilize (to a certain degree).

As a result, price-sensitive customers will start to seek out value-oriented options when dining out. The demand will always be there, even if discretionary spending is somewhat tapered. There will be an opportunity for value-oriented operators to take some market share in the near-term.

Do you think some brands will turn to value when things settle down? What might that look like?

I jumped the gun a bit with my previous answer—but yes, definitely. People are going to be a bit more strategic with their discretionary spending. Operators will have a big incentive to reduce operating costs and overhead expenses (optimize staffing, input costs, and location layout) where possible. Those that can achieve this while still offering strong customer service and an experiential dining option will thrive.

How is minimum wage going to factor in? It almost feels like this topic got pushed aside by COVID as restaurants were forced to pay more for labor just to recruit. Is that about to change?

For the time being, minimum wage shouldn’t be a major factor in the industry. Per the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, average hourly wages in the leisure and hospitality industry were $19.35 in February 2022—an 11.25 percent increase versus February 2021 and a 14.5 percent increase vs February 2020 (pre-COVID). Tip credits, where applicable, will still play a role as operators juggle how to improve employee compensation and benefits in an unstable environment.

Until the labor supply imbalance resolves itself, the bigger headline will be how restaurant operators are fighting to attract talent.

Diving deeper into labor, will owners have to start hiring unvaccinated employees again to cover increased demand?

Job openings in the leisure and hospitality industry stood at about 1.7 million in January 2022, roughly 115 percent above January 2021 and 76 percent above January 2020 (pre-pandemic). At the same time, total employees for food and drinking places are still about 6 percent below pre-pandemic levels (January 2022 versus January 2020). Long story short, persistent labor shortages continue to weigh on the industry.

Back in August 2021, I wrote about how “operational stability and consumer confidence are critical factors in the economic recovery of the industry, and this requires complying with federal, state, and local health ordinances and keeping staff safe and on the job.” As mask and vaccine mandates are slowly repealed nationwide, I think we will see operators look to any qualified, available pockets of the labor pool to fill their staffing gaps.

How fierce is that battle for talent going to be, and are there changes in the system it will impart for good, like better benefits, workplace reform, etc.?

The battle for talent has been fierce for a while now, and it shows no signs of slowing down in the near term. Service industries (restaurants, retail, hospitality, etc.) face a unique challenge, as a large swath of the labor force used the lockdown period to reevaluate their options. Many pivoted to industries with comparable pay and benefits, but potentially favorable work-life balance. In talking to some clients, many of their top-tier talent wasn’t lost to a competitor, but to a pivot away from the restaurant industry in general.

To attract talent back to the industry, many operators are working to strengthen their benefits offering, implement more refined career progression upside, and are trying to create a more stable work-life environment. At the same time, operators are investing in technology to optimize staffing and improve efficiency—reducing employee burnout. Much of this will be sustainable in the long-term, to the benefit of the employee pool.

Urban restaurants have enjoyed expanded sidewalk seating capacity without a subsequent tax increase, essentially padding their margins. How will the reduced capacity impact their bottom lines?

As a New Yorker, increased outdoor dining (plus the to-go drinks) was a bright spot during the pandemic. While some operators invested in long-term structures such as patios, many will need to remove the impromptu outdoor infrastructure.

While outdoor dining enhanced seating capacity, many operators were still constrained by staffing shortages—effectively limiting capacity to the original location design pre-pandemic. The impact on margin may not be material in those cases. In fact, it might even improve the labor mix issue.

That being said, there is a portion of the consumer base that enjoyed the outdoor dining option—especially in the spring and summer months. Removing the option might dissuade some potential customers or see them pivot to a to-go option. This aspect is hard to quantify currently.

There will likely be some margin impact from this shift, although I think inflation and labor issues will be the big headlines for the foreseeable future. Outdoor dining will become another piece of the puzzle for operators to evaluate when considering long-term design and layout strategies.

It feels like the big chains just keep getting bigger now, with independents looking at years of recovery. Do you believe that’s going to hold? Or will the consumer demand shift the landscape at some point?

Larger chains with stronger balance sheets were able to take advantage of government stimulus, a favorable landlord environment, and vendor concessions to seize the opportunity for expansion. These chains have also done a great job pivoting based on consumer preferences—optimizing their resources via ghost kitchens, digital-only restaurants, and expanding into new service offerings. At the same time, independents, with limited resources and bargaining power, have struggled.

There will be a bit of mean reversion here, especially as COVID-driven momentum subsides. The restaurant industry is always ripe for innovation, and there is always demand for fresh, unique service offerings. I think you will see independents start to adapt and innovate, it will just take some time—as these platforms need to be a bit more strategic (cautious) with their capital investments.

What do you think will be the biggest shift from this era?

Given everything that is going on, it’s a bit tough to tell. My thesis is that labor and inflationary pressures work in cycles, and things will subside at a new “normal” sometime down the road (12-plus months).

The biggest long-term shift will be in the breadth and scale of dining alternatives – as customer preferences have evolved over the last 24 months. Operators are experimenting with new floorplans and modified customer interface/point-of-sales systems. Casual dining operators are testing out fast-casual alternatives. Chains are investing in digital-only restaurants while others are optimizing their existing infrastructure as ghost kitchens. Third-party delivery and to-go infrastructure are legitimate considerations. Supply chains are being redesigned as lifestyle brands enter the market (e.g., MrBeast Burger or Another Wing). A lot of this is still in the “test” phase and some of this will not be long-term viable. But much of this investment stems from a shift in customer preferences, and it will change the way we view the industry in the coming years.