It was a dark day in September when Britain’s National Pig Association broke the news that pork products—including everyone’s favorite, bacon—would soon become a luxury because of dwindling pork supplies from the ongoing drought in the U.S.

Though consumers around the world were left clutching their pearls, it was much ado about nothing, as economists and commodity experts quickly debunked the theory. But the media hype did turn a lot of eyes—both consumers’ and foodservice industry insiders’—to the real issue at hand: rising commodity costs.

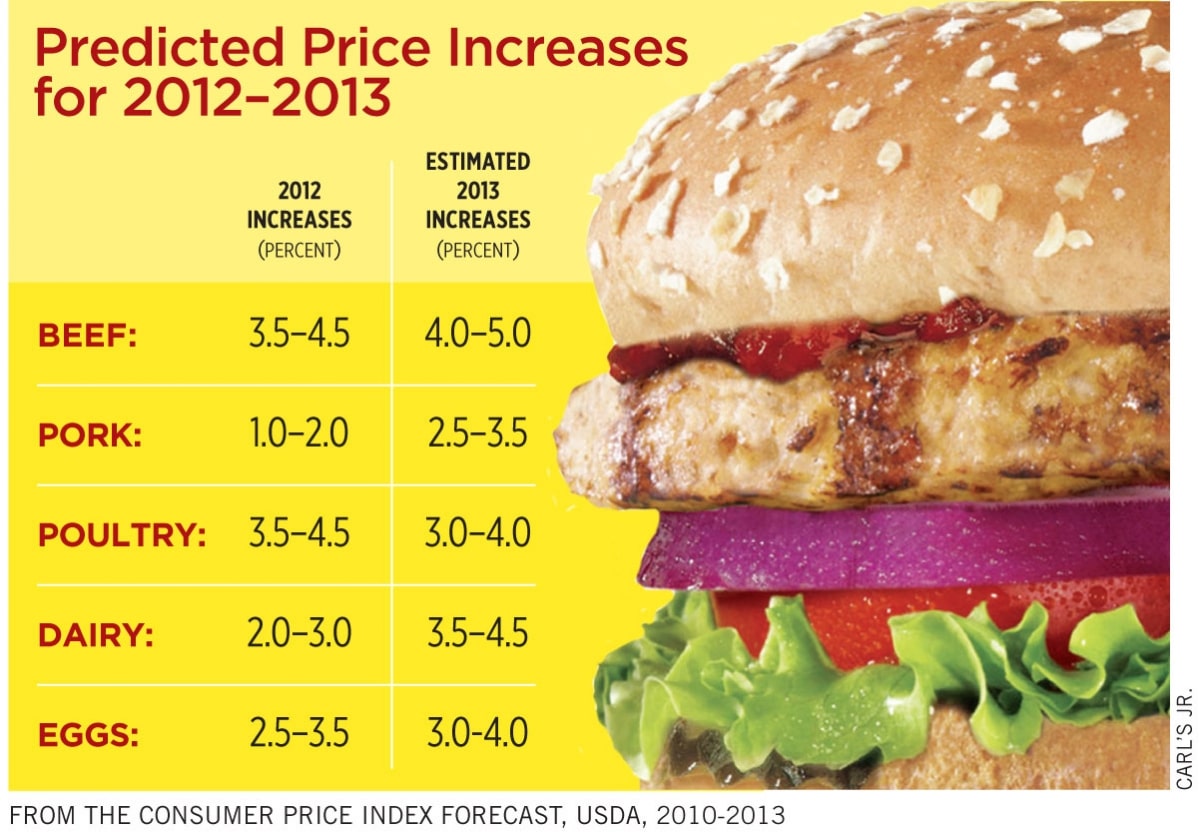

Largely because of 2012’s severe drought in the Midwest and other parts of the U.S., it’s become widely accepted that wholesale price increases for animal products like meat, eggs, and dairy are unavoidable. But just how serious the problem is and how detrimental to quick serves’ bottom lines it will be has yet to be seen.

Suffering through a dry spell

What started as a promising year last spring, with a record corn crop in the ground, quickly turned to devastation as Midwest farmers saw little to no rain through the summer and fall.

“We were looking at a 20–25 percent reduction in the original forecast for both [corn and soybeans last year],” says Ricky Volpe, an economist with the Economic Research Service for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). “This, of course, has an impact on prices, because it’s a reduction in supply.”

When natural disasters like droughts strike, corn prices skyrocket, making it more difficult for ranchers to feed their animals, experts interviewed for this story say. To stay above water financially, ranchers are forced to liquidate herds, sending them off to slaughter much sooner than usual. While this momentarily causes an increased supply and drop in prices for items like pork and beef, it’s quickly followed by increased prices as supply fades.

Because it takes up to two years for farmers to raise, fatten, and send cattle and swine to slaughter, a drought can cause trouble for months and even years to come. “Until such a time that feed prices come down to a point where the producers are making money again, there’s going to be no incentive for them to expand production,” says John Barone, CEO of New Jersey–based Market Vision, a restaurant commodities consulting firm. “You’re in a tight supply situation going forward, and that’s the drought’s biggest impact this year.”

Since food costs are such a large burden for restaurants, rising commodity prices can directly affect a brand’s bottom line in a dramatic way.

“When you think about a typical restaurant-industry sales dollar, roughly a third of that goes to cover operator-direct purchases of food and beverages,” says Hudson Riehle, senior vice president of the National Restaurant Association’s (NRA) Research & Knowledge Group.

“When it’s that large a proportion of operating costs, even modest increases can result in operators needing to reengineer not only their internal cost-operating structure, but also their menu.”

Protecting the customer

Though experts expect a share of the resulting price increases to be felt by everyone along the supply chain—including producers, suppliers, operators, and even consumers—many chains are battling to keep the burden off consumers’ shoulders.

“Normally the way that you deal with commodity costs in the restaurant industry is to raise prices. It’s something that every restaurant has always done and it’s how you keep up with inflation, it’s how you keep up with increases to minimum wage, and it’s how you keep up with increased commodity costs,” says Andy Puzder, CEO of CKE Restaurants, which owns the Hardee’s and Carl’s Jr. brands. “The problem now is that the economy is in such distress that it’s difficult to raise prices.”

While brands need to tiptoe around price inflation to keep consumers happy, traffic counts up, and sales strong, raising prices may be a challenging but necessary evil. “In the more modest economic environment, obviously operators can’t pass through on a one-to-one basis what happens with their higher input costs,” the NRA’s Riehle says. In fact, while wholesale food prices were up 8.1 percent in 2011, he says, menu prices were only up 2.3 percent.

Larry Reinstein, president of Charlotte, North Carolina–based Salsarita’s, says the brand will try to hold the line as much as possible when it comes to price hikes, but will likely have to raise prices. “The key is to be modest and strategic, because we want to continue to deliver the best value we can for our guests,” he says.

Reinstein says the lag time between when the drought took place and when the market will see its pricing effects poses an additional obstacle. “People’s memories are short, and the drought happened this past summer,” he says. “By the time a lot of the effects of what happened with the drought takes place, … I just wonder if the consumer is going to realize what’s going on as restaurants and supermarkets and everybody else is forced to raise prices.”

[pagebreak]

Locking down contracts

To help curb costs from rising commodity prices, operators are looking ahead of the market and scrambling to lock in any product contracts they can, lowering prices when possible.

“When the drought hit us, what we did was we very quickly got together with our economists and our supply partners, and we tried to put some short-term strategies in place,” says Alice Le-Blanc, chief global supply chain, commercialization, and quality assurance officer for Popeyes Louisiana Kitchen.

Though the brand continues to lock in annual contracts when possible, it also considers converting some yearlong contracts to three- or six-month terms. “At the end of the day, we want to work with our supply partners to ensure that they, too, are staying profitable,” LeBlanc says, “because if any of our supply partners suffer, then we won’t have continued supply. If it means going on a three-month contract, then that’s what we have to do.”

Bruce Reinstein is the vice president of strategic development and sourcing for purchasing firm Consolidated Concepts. He says if the firm anticipates excessively higher prices over the contract period, it will opt for 90- or 180-day contracts for its clients. However, these shorter contracts can make menu planning more difficult. “The worst thing is to put together a menu for the year and then you have a three-month contract, and all of a sudden your products go up 20–25 percent,” he says.

Instead, he says it may be worthwhile to lock in a 10–12 percent increase for a full-year contract, even if there’s a possibility that markets may drop by the end of the year.

“At least what you did is you kind of averaged it out,” Reinstein says. “You paid a little bit more at one point in the year, a little bit less at one point, but if you can get that long-term contract and you feel it’s a fair contract for everybody involved, it gives you a little more peace of mind.”

Capitalizing on limited-time offers

With uncertain prices and product contracts, operators are turning to limited-time offers as a more economically sound menu-planning approach.

“[Restaurants] have to be much more nimble than they used to be,” Consolidated Concepts’ Reinstein says. “They have to be looking at limited-time offers that they’re not tied in to for real long periods of time because the markets are going to change, potentially even during that limited-time offer.”

The team at Salsarita’s, which has 80 stores across the East Coast, Midwest, and South, takes advantage of market movements by planning its LTOs on a short notice. “We make a point with our LTOs of not going too far out, so we’re nimble enough that we can still affect what we decide to do [this] spring, summer, and fall,” Larry Reinstein says. “One of the advantages of a company that’s not as big is you can run different types of LTOs, you can do different things in your restaurants, and you can move a lot quicker.”

Jeff Forrester, director of purchasing for Dickey’s Barbecue, says that because beef prices are rising at a faster rate than those of pork or chicken, the brand developed a new Barbecue Honey Ham to build sales and maintain its cost of goods throughout the year. “We’re always looking at ways to increase our breadth within the marketplace and give our customers the best products we can for the money,” he says.

And though it specializes in chicken offerings, Popeyes will set itself apart while saving money by playing up its seafood offerings, LeBlanc says. The brand plans to bring back and emphasize popular limited-time seafood promotions like its Butterfly Shrimp Tackle Box and the Crawfish Festival.

Preying on poultry

Because items like beef and pork are taking the biggest beating from lower supply and higher feed prices, many brands are going down a different protein path to cut costs. Experts say poultry will remain the cheapest protein—largely because of its shorter production cycle of around six weeks—leading brands from all segments to highlight existing chicken products or develop chicken-based limited-time offers.

McDonald’s and Burger King have reinvested in their chicken offerings in recent months, with items like Chicken McBites and the Chicken Parmesan Sandwich, respectively. Bruce Reinstein says brands could even think outside the box by exploring dark meat or promoting chicken legs instead of wings.

“For the past two years, all of [the] restaurant chains have pretty much bailed themselves out by promoting chicken breasts in any way possible,” Market Vision’s Barone says. He adds that though chicken breast prices were up 10 percent last year, 2011 was a record-low-price year. “So even if we take another increase [this] year, historically, chicken breast is still going to be relatively inexpensive,” Barone says.

While CKE brands offer chicken tenders, chicken sandwiches, and charbroiled chicken breasts, they also offer something many other quick-serve chains don’t: turkey burgers. Puzder says the brand is introducing a jalapeño turkey burger this month in anticipation of rising prices for other proteins. “We think that we can switch to other proteins like turkey, for example, or chicken if we needed to, if beef goes too high,” he says.

Searching for a turnaround

The USDA hopes major price increases will work their way through the system by the midpoint of the year. However, “We’re at this new plateau of higher prices for beef and pork, and we expect them to continue to increase through 2013 and probably beyond,” Volpe says.

Not only does the speed of recovery depend on weather conditions going into spring—a hefty dose of rain would likely remedy the situation—but it also hinges largely on farmers’ and ranchers’ actions. Barone says many of them will wait to see what kind of corn crop they plant this spring, as well as how high corn prices will be, before deciding to expand herds again. But even then, immediate relief won’t be found for items like beef; after all, ranchers have to breed cattle and raise them to slaughter.

“That is a two to two-and-a-half-year process,” he says. “At the very, very closest, we’re not looking at expanded cattle supplies until the middle of 2015. We’re talking all of 2013 and 2014 for elevated beef prices, and possible record-high prices for spring 2013.”

However, some in the industry believe at least a portion of the problem’s severity can be eased by operators’ reactions. “Commodity prices are like oil prices. They go up for two reasons: One is an actual demand that exceeds supply, and the other is an anticipation that demand will exceed supply,” CKE’s Puzder says. “The anticipation itself can impact prices, even though the actual supply may be there. If people are patient and kind of look at the history of where these things go, we’ll see that it may not be as bad as people think.”