There isn’t a lot of mystery regarding pricing of late. The restaurant industry has become a more expensive world to operate in, thanks to a bevy of macroeconomic pressures. In turn, prices continue to tick up as brands lean on a willing consumer. Jim Balis, managing director of CapitalSpring’s Strategic Operation Group, told FSR the firm, which has invested $2 billion across more than 60 brands, historically sees restaurants take price once or twice a year. In 2021, it was closer to four.

This is largely a blanket point. Prices for food away from home increased 5.3 percent year-over-year in October, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Quick-service menu items rose 7.1 percent, while full-service meals upped 5.9 percent. Each marked the largest 12-month increase in recorded history.

Inflation overall in November was up 6.8 percent, the highest since 1982. Restaurant menu prices climbed 5.8, year-over-year, with limited service hiking 7.9 percent and full service 6 percent.

So far, customers haven’t shied from the price tag. Bank of America aggregated card data showed spending on restaurants and bars, on a two-year comparison to 2019, is up 20 percent.

According to industry tracker Black Box Intelligence, industry sales in November were 8.3 percent stronger than two years ago. With a 2.3 percentage point improvement over October’s growth rate, November represented the best month based on sales growth in more than a decade.

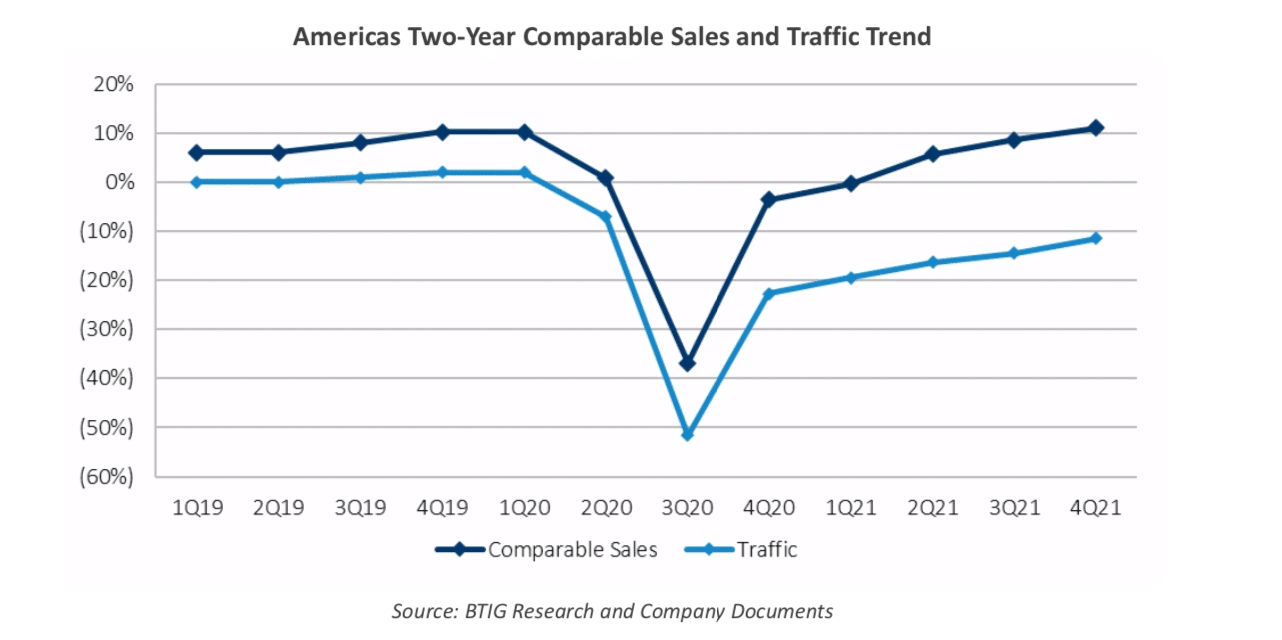

However, traffic growth was negative at 4.7 percent, slower than April, June, and July. Guest counts are not pacing parallel to sales, suggesting a twofold trend: Check expansion, thanks to higher prices, alongside off-premises adoption, are pushing this recovery line forward.

Unlike higher costs, though, predicting consumers’ willingness to keep opening their wallets isn’t as clear. Balis believes, ultimately, the restaurant guest “is going to say enough is enough.” Although, he added, the fact prices are surging at grocery stores, too, has helped. “The consumer is looking at the alternative and realizing going out to eat isn’t much more than cooking at home, and in some cases dining out is potentially less expensive,” he said.

So where is the breaking point? Fazoli’s CEO Carl Howard thinks restaurants will find out in 2022 when “stealth inflation … smacks the consumer right in the face.”

“We’re coming to a pretty significant point right now,” he says. “The consumer is paying a lot more for gas. They’re going into the winter having to pay a lot more for natural gas. So they’re going to get beat up. Restaurant prices are, I’ve heard in some cases, 10 percent higher. Grocery prices are through the roof.”

“You’re going to see a rapid rise in the value menu,” Howard adds of the response from restaurants.

It’s a prediction shared by BTIG analyst Peter Saleh. After a “long and extended hiatus” during COVID, value offerings and messaging are going to creep back onto restaurant menus as stimulus dollars subside and the impacts of inflation weigh on the consumer, Saleh said.

“Value offerings and messaging have been scarce since the pandemic began, as many concepts have focused on driving the average check with core products and more limited menus,” he said.

Saleh predicts this battle for transactions will shine focus on value price points throughout quick-service’s top tiers, including 2 for $5, 2 for $6, or even the $1, $2, $3 menu at McDonald’s.

BTIG surveyed 1,000 U.S. consumers to poll their quick-service dining habits and see where this puck might be headed. On a base level, it showed higher-income customers flocked to quick service during the pandemic more frequently than before (thanks to the drive-thru and tech) and that guests have noticed price changes more than anything else over the past six to 12 months. Staffing, or lack thereof, was a close second.

Saleh said record-high commodity inflation will weigh on “almost all” operators in 2022, with more margin pressure early in the year and less in the back half. “We expect the moderation in commodity prices to be led by beef and chicken as production levels catch up with demand as employees return to processing jobs,” he noted. “That said, given the commodity lead times for many operators, we don’t expect the benefit to be realized until one to two quarters after prices have significantly come down.”

Considering the backdrop, as the “value wars” pick up momentum into the new year, Saleh expects brands that cater to more affluent consumers to weather early setbacks, like Starbucks. Chains with pricing power that court higher-income demographics.

Early hurdles such as mobility, tourism, and workplaces will only drive further upside. Saleh predicts Starbucks will throttle pricing in 2022 to support margins, offsetting most, if not all, of the wage and labor investment the company announced in October.

Saleh said a 4–5 percent price increase should cover the entire North America bill.

As a refresher, Starbucks plans to invest $1 billion in incremental annual wages and benefits, something that will unfold in stages. By summer 2022, the company will offer a starting wage of at least $15 per hour for store-level workers, making good on a promise from December 2020. Come January, employees with two or more years tenure will receive up to a 5 percent raise and those with five or more years will see wages lift 10 percent. In all, Starbucks said hourly U.S. employees are set to make an average of nearly $17 an hour with baristas taking in $15–$23.

A reason this is so vital—over the past 12 months, 70 percent of Starbucks’ hourly employees were new to the brand.

Retention, not recruitment, could become the true labor fight of 2022.

Returning to value, the landscape of the past 19 or so months saw quick-service brands trade lower-income consumers for higher-income ones.

As Howard explains, the pandemic “forced people to use restaurants with drive-thrus more often.”

“A lot of their favorite restaurants were either closed, or permanently closed, and they had less options, and they gave us a try again,” he says. “And they found out just what a tremendous value we have at Fazoli’s.” Howard calls that re-introduction, or introduction, “the advertisement I could never afford.”

Saleh said quick-serves, everybody from McDonald’s and Wendy’s to Chipotle and Starbucks, benefited from digital and off-premises capabilities as COVID stretched on. Those channels flooded more affluent consumers in, but perhaps at the expense of ceding share among lower-income guests.

In the past year and a half, 19 percent of respondents in BTIG’s 1,000-consumer survey indicated they visited quick-service brands more often than pre-virus, as noted earlier. Yet digging deeper, 29 percent of respondents earning $150,000 or more annually claimed they frequented fast food more, while only 16 percent in the $25,000–$45,000 per year range said the same. “We believe this dynamic aided the growth in average guest check, driving total sales back above pre- pandemic levels despite lower transactions counts,” Saleh said, which reflects Black Box’s November data.

Quick-service visit frequency during the pandemic (per BTIG research)

- I visited about the same as I did pre-pandemic: 38 percent

- I visited less often than I did pre-pandemic: 33 percent

- I visited more often than I did pre-pandemic: 19 percent

- I don’t eat at fast-food restaurants:10 percent

As the economy reopens and resets to whatever “normal” looks like now, Saleh expects the benefits from higher average guest check to wane sector-wide. Meaning, growth will need to come from guest count improvement.

For that to happen, as history tells us, quick-serves will need to regain footing with lower-income consumers or the “value seekers” the category built its foundation on.

“We believe many of those lower-income consumers are searching for lower price point offerings or value deals,” Saleh said.

BTIG’s survey showed more than half of consumers (52 percent) said they’d visit fast-food restaurants more often in the coming months if they provided greater value and lower price points. Guests picked greater value over menu innovation (another strategy that’s been mostly absent during the pandemic), faster speed of service, and healthier menu options as the factor that would cause them to increase their visit frequency.

Not surprisingly, Saleh added, lower-income consumers were motivated by value offerings more so than any other group. Over two-thirds of people in the $25,000–$35,000 per year range said value and lower prices would send them to quick-serves this coming year.

That compared to just 35 percent of consumers earning $150,000 or more.

What would entice you to visit quick-service restaurants more often?

- Greater value or lower price options: 52 percent

- New menu options/innovation: 48 percent

- Faster service: 33 percent

- Late-night hours of operation: 20 percent

- No minimums for delivery: 19 percent

- Had a steady/better job or budget: 17 percent

- Plant-based meat menu options: 15 percent

- None of the above: 11 percent

- Other: 6 percent

What this also portends is there will, eventually, be some kind of price ceiling. BTIG’s survey showed 58 percent of respondents have noticed price changes at quick-service restaurants recently, slightly higher than those who’ve taken stock of staffing problems (56 percent), changes in operating hours (48 percent), and menu options (36 percent).

Of those who noticed price hikes, 55 percent said increases have been “slight” or “modest.” Yet 38 percent called them “significant.” And completing the value loop, consumers who classified recent price changes as such tended to be lower-income diners: About 45 percent earned less than $35,000 per year. Only 16 percent of respondents making $150,000 agreed.

Darden CEO Gene Lee, speaking on an earnings call in September, cautioned “at some point, your average consumer could get priced out of casual dining if it costs too much.”

And that’s talking about brands like Olive Garden and LongHorn Steakhouse. It’s why the former notched two-year check growth of only 2.4 percent, electing to row in the reverse direction of many of its peers as a long-term play. “People are saying, well, we’re pushing this off [price] and I guess, no one is pushing back. Eventually, it’s going to be pushed back,” Lee said.

Fazoli’s, Howard says, self-inflicted 120 days of margin erosion during one pandemic run to offer value deals like a 5 for $5 program. “I didn’t care because we introduced people to the brand,” he says.

That effort is about to switch gears into remarketing, Saleh said. Quick serves are going to reposition value to win back guests and remind potential lapsed ones. And also, just to reflect an inflationary environment where cash-wary consumers look to quick service for the value they expect.

Many of the consumers surveyed by BTIG indicated price increases would affect their visit frequency. In fact, 49 percent said menu price lifts were significant enough to make them look elsewhere. Forty-four percent said they don’t expect to change their habits. Once more, these figures skewed toward lower-income consumers, with nearly 60 percent of respondents earning $25,000–$35,000 claiming price increases were noticeable enough to make them visit less often. Just 39 percent of consumers in the $150,000 and above range indicated the same.

“We believe a return to a more normalized operating environment in 2022, characterized by more meaningful value promotions and discounts, could limit earnings upside for many quick-service restaurants and, in turn, overall stock gains,” Saleh said. “We expect operators that cater to more affluent consumers with greater tolerance for price increases to outperform in 2022.”

That brings Saleh back to Starbucks. There are a few reasons he expects the java giant to outperform large-cap counterparts in 2022. Firstly, he said, earnings estimates have been reset much lower following last quarter, as the company’s investment in labor dragged its margin and earnings per share outlook by about 400 basis points and 84 cents, respectively.

But more to the future point, Saleh feels investors are overlooking Starbucks’ unique pricing power. Also, Saleh said, Starbucks’ margin estimates provided last quarter overshadowed an acceleration in unit development, which picked up 220 basis points to 5.8 percent from 3.6 percent in full year 2021 (4.5 percent in full year 2020). Lastly, there’s still benefits to attain from the chain’s trade area transformation, notable for a push toward more suburban and drive-thru anchored stores.

“Even though management has not provided specific pricing plans, we believe the brand has opportunities to raise menu prices more aggressively, as many of its peers, including McDonald’s and Chipotle, are operating with mid- to high-single-digit pricing,” Saleh said.

Simply, higher menu pricing at Starbucks is a near lock. Raising prices 4–5 percent would equate to roughly 30 cents on the average guest check. “A fairly modest amount for a premium product,” Saleh said.

In addition, Starbucks, as other competitors did, bypassed a pricing window at the heart of the pandemic, which gives it plenty of opportunity to catch up this year.