It’s been more than four years since Popeyes’ chicken sandwich landed like a meteor. The company fulfilled as many orders in 14 days as it projected over the following month and a half, leading to Popeyes famously running out of supply. Some stores reported serving 1,000 chicken sandwiches per day, and one tweet (the now-infamous challenge to Chick-fil-A) ended up garnering north of 20 billion impressions, according to Ad Age. Or some $220 million worth of media.

Overnight, Popeyes president Sami Siddiqui said at this year’s QSR Evolution Conference, the penetration of the brand grew 33 percent—an unheard-of figure that not only rocketed Popeyes, but took an entire category along with it. By the time 2019 closed, Popeyes had more than doubled its Twitter following and had so much word-of-mouth force it canceled an ad campaign scheduled for Labor Day.

Popeyes before the chicken sandwich earned roughly $1.4 million per restaurant annually on the top line. That rose to $1.8 million (it was $1.823 million in 2022). The trial Popeyes created from the campaign cascaded as guests came in, got the product, and looked around. “It elevated us and really catapulted us from this more niche, regional brand to being a mainstream brand,” Siddiqui says.

Naturally, Siddiqui, the former president of parent company Restaurant Brands International’s Asia-Pacific region before taking his current post in September 2020, has been quizzed “what’s next” for a while now. Where does buzz mature into something else?

Popeyes conducted internal research to ask a simple follow-up: How far does a chicken sandwich guest have to drive out of their way to get one? On average, it was 10–12 minutes. Going back, if there’s one thing Popeyes’ sandwich spawned, it was a flurry of competitive entry that’s still going on today. Everybody from Taco Bell to KFC to Zaxby’s to fast casuals of every ilk and awareness tier crashed “The Chicken Sandwich Wars” with a mirror goal: “Try ours to see who’s best.’” And like clockwork, each contender invited Popeyes to reenter the fray.

But in the end, what the “battle” gave customers was a lot of chicken sandwiches to choose from. “There’s too many chicken sandwiches between that guest and our restaurant,” Siddiqui says of the 10–12-minute drive. “That’s just the reality.”

This observation wasn’t new to Popeyes; its urgency had simply changed in hopes of capitalizing on momentum. When RBI acquired the brand on March 27, 2017, for $1.8 billion, there were about 2,600 locations in the U.S. and 25 countries globally. From acquisition to 2020, RBI posted cumulative net restaurant growth of 27 percent at Popeyes. The first, non-COVID rattled year following the chicken sandwich—2021—represented the highest number of openings as the brand closed with 3,705 restaurants globally—a net of 254 stores, or unit growth of 7.4 percent.

Fast forward and Popeyes finished Q1 2023 with 4,178 restaurants globally—2,947 in the U.S. and 1,231 internationally. There were more than 200 North America debuts in 2022, featuring the loftiest figure of new franchisees and the largest percentage of freestanding single or double drive-thru locations in five years.

The broad point being, Siddiqui says, even with recent acceleration, Popeyes remains a bit subscale compared to others in the category. KFC finished 2022 with 3,918 stores in the U.S. and an eye-widening 23,842 international restaurants. Chick-fil-A had 2,837 domestic units at year-end 2022, with Wingstop at 1,721, Zaxby’s 922, Church’s 812, and Bojangles 788.

In his first year at the helm, Siddiqui traveled across America, meeting employees, franchisees, and even conducting ride-alongs with guests. Popeyes commissioned consumer research to “get at the heart of what does Popeyes mean to our guests and our franchisees,” Siddiqui says. And one thing that popped was a fundamental truth of the brand, started by Alvin C. Copeland Sr. as “Chicken on the Run” in the New Orleans suburb of Arabi in 1972: When done right, data showed, guests love Popeyes’ food. “We are a taste leader,” Siddiqui says. “The food is distinctly Louisiana. There is that shatter crunch to the chicken. There is simply something special to what we do when we execute well.”

Interestingly, however, the point presented a paradox that goes back to the sandwich distance data. The average Popeyes guest visits the brand three times per year. The industry average in quick service is closer to 10. McDonald’s might be more in the realm of 18–20. “That’s a massive gap,” Siddiqui says, “and that was the foundation of, or this problem statement that we were trying to solve—how do we get our guests to be more frequent guests of Popeyes?”

The second point that surfaced was when guests did locate a Popeyes, the service experience was not always consistent. Sometimes it was slow. Other days hospitality lacked. “We have to fix that,” Siddiqui says. “And so, coming of that as well as the staffing crunch of the pandemic and thereafter, we started thinking about what we need to do in this category, which is premised on convenience, reliability, and being easy is, we need to make Popeyes ‘Easy to Love.’”

Popeyes earlier this year unveiled a multi-year plan to increase average four-wall profitability to $300,000 by the end of 2025. That’s the bones of “Easy to Love,” a tagline and direction Siddiqui shared at the chain’s annual franchise convention in Phoenix in front of 600 participants.

Siddiqui says it’s essentially a threefold blueprint—make Popeyes Easy to Love for guests; Easy to Love for team members; and Easy to Love for franchisees. “If we can get that done,” he notes, “that’s success in my mind.”

And unsurprisingly, it’s a journey that trails back to the chicken sandwich, or what Siddiqui refers to as the “most innovative, game-changing thing that we’ve done at Popeyes in our 50 years.” The sandwich shed the brand’s niche or “cult-like” approach. Because, by definition, cults are outside of the mainstream, and Popeyes was getting love from Beyonce. Additionally, going from $1.4 to $1.8 million AUVs enabled franchisees to start investing back in the business, an aim sister brand Burger King is currently working toward.

The chicken sandwich today isn’t so much a product as it is a platform. On Tuesday, Popeyes launched a Spicy TRUFF option topped with TRUFF’s Spicy Mayo. The Blackened Chicken Sandwich, which was developed in response to guests asking for a lighter version, became a permanent addition to Popeyes menu in June, marking the first full-on change since the 2019 launch. “That’s the way we think about the future of the category, is building platforms off some of these growth things, like the chicken sandwich,” Siddiqui says. In another example, Nuggets entered the picture in July 2021.

With Easy to Love, improving customer service starts with serving team members better, Siddiqui says. He frames it as making restaurants “easy to run.” Siddiqui had a few aha moments along this path.

When he became president, Siddiqui got into restaurants and worked the line. He’s done the same at Burger King and Tim Hortons. And it was clear, from the jump, Popeyes was a different kind of fast-food box.

The brand’s bone-in chicken comes in fresh to restaurants, never frozen. It’s marinated 12 hours or more in-store, hand-battered, hand-breaded, tossed in flour 20 times, and fried for 12 minutes. “That is a ton of care that goes into that product,” Siddiqui says.

Chicken only sits for 30 minutes in Popeyes’ “birdcage.” So any time a guest eats a piece of bone-in chicken from Popeyes, the longest time it’s rested is half an hour. “That is very hard to execute at the restaurant level, particularly in [quick service],” Siddiqui says.

The next realization for Siddiqui pulsed during a global tour. Over a stretch of roughly six months, Popeyes’ team travelled to international markets and jotted down best practices. Siddiqui and SVP Jourdan Daleo went to Spain and saw what a market starting from scratch looked like. What is the blank canvass of Popeyes? Of course, food quality was atop the core, but so was a kitchen that flowed more efficiently, anchored by new equipment, built to think about what the present and future guest is asking of the brand.

Ultimately, the learnings boiled down to a few notions. No. 1, Siddiqui says, was rethinking layouts. For instance, when Popeyes added things like the chicken sandwich to restaurants, it didn’t have room for a sandwich station. They’re off to the side, which doesn’t make a ton of sense from a flow perspective for a product firing up transactions at unseen levels. There were also some processes, Siddiqui says, Popeyes could have suppliers take on or layer innovation around. “You put that all together, Popeyes becomes easy to run and then it becomes much easier to love for our guests,” he says.

Regarding innovation, Popeyes had to refocus the lens. Post-COVID, the percentage of guests coming inside, ordering, and eating food on-site at a Popeyes was just 10 percent of the entire picture. Drive-thru about 60 percent.

If you stretch back to 2018–2019, the chain’s standard restaurant had 72 seats. Today, Popeyes is building units with anywhere from 25–35. That arrangement was cut in half. But these stores aren’t opening on freestanding lots with significantly less land. Rather, Popeyes is pushing more volume through kitchens and into an omnichannel universe than the café itself.

The dynamic presents equal parts opportunity and challenge for Popeyes, as it does likewise through fast food in the wake of COVID. The chain has worked to physically bridge the gap through kiosks. A Times Square store opened with self-order kiosks, a two-story food transporter for upstairs dining, digital order-ready boards, and a merchandising store inside. It was a design that mirrored a restaurant Popeyes unveiled in March 2022 when it re-opened the company’s New Orleans landmark on Canal Street. The 200-year-old building represented the domestic introduction of the “NOLA Eclectic” image Popeyes said it was carrying to New York, which first launched in Shanghai and also included dedicated space for digital-order pickup.

Popeyes said last year more than 50 percent of pipeline stores featured double drive-thru designs. In 2022, over 70 percent of openings had at least one drive-thru and were either with top-tier existing franchisees or new franchisees (a sign reflective of the improved cash flow from AUVs).

Siddiqui says Popeyes continues to consider guest trends in its restaurant models. Can the chain integrate loyalty through drive-thru? “If 60 percent of our guests are coming through the drive-thru and we can’t get them into our loyalty—that’s a huge missed opportunity for us,” he says.

What about AI? Robots won’t be making chicken at Popeyes anytime soon. “We’re not there yet,” Siddiqui says.

Yet there are foundational tech pieces, like digital drop charts, proving capable of making Popeyes’ business smarter; unlocks that allow it to know how much food to cook, when to cook, etc., which can then make employees’ lives easier and save on food costs. “To the extent that we can strengthen that foundation on the tech side, it’s going to make our guest service that much better,” Siddiqui says.

Returning to the largest barriers facing Popeyes’ frequency following its chicken sandwich intro, the constant kicker remains “convenience.” That’s either a numbers game, in regard to material store count, or an operational one, like speed of service. Siddiqui says technology and digital—which now accounts for 20 percent of the business—offer wide potential.

Popeyes sees today’s digital marketplace as a massive storefront. If it can deliver convenience through digital experience, then, suddenly, Popeyes is a lot closer to consumers. “Third-party delivery is a great example of that,” Siddiqui says. “A lot of people said, ‘hey, you know I’ve heard of this Popeyes brand, but I’ve never seen a Popeyes near me.’ But if you fire up DoorDash or Uber Eats, all of sudden you have a Popeyes in front of you. You may not think that’s 6 miles away—that’s right in front of you.”

The conversation translates into asset evolution as well. Traditionally, Siddiqui says, quick-service brands sought freestanding, top-tier real estate where you could throw big boxes on large pieces of dirt. But the reality now is there are fewer such opportunities in big municipalities. Can you build a digital location and walk-up, however, to see what demand might be? And, maybe, complement that with different formats around it? “That’s what digital does,” Siddiqui says. “It gives us flexibility to get closer to the consumer, as we think of the guest side.” Popeyes has done this before. In South Florida, where RBI has a Miami base, there was a trade area Popeyes hadn’t tried to break in before; there was no availability for a sizable, freestanding site with a drive-thru. So Popeyes opened a digital-only concept with kiosks, no registers, and a kitchen equipped to handle delivery and mobile order and pay.

Overseas, underpenetrated

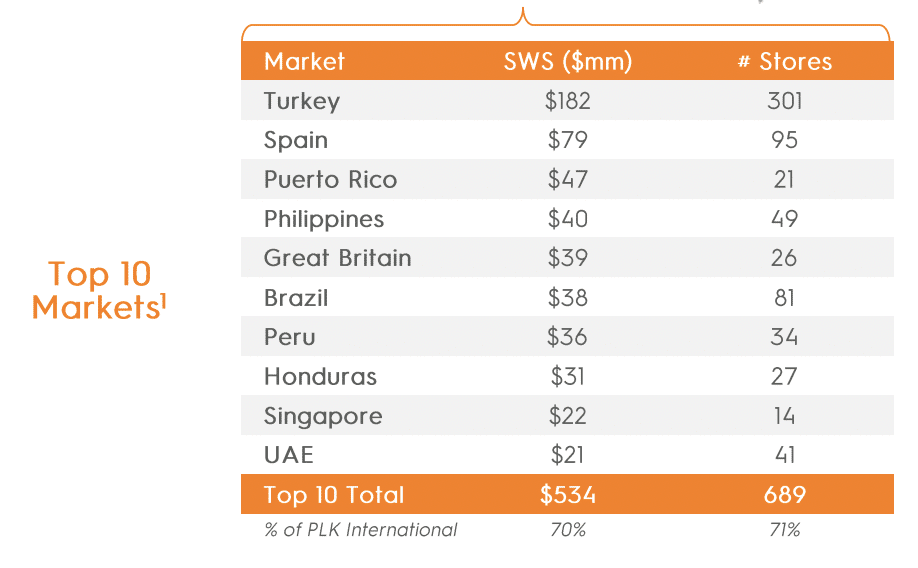

To label Popeyes’ international runway “sizable” would be like calling its chicken sandwich “successful.” It only grazes the fact. The brand produced about $760 million in systemwide sales outside the U.S. last year across 1,000 or so locations (Popeyes’ domestic business produced a touch over $5 billion in 2022). It’s a base of stores you could fit 24 times into KFC’s international footprint.

Here’s how Popeyes’ overseas store count has tracked:

2018: 578

2019: 626

2020: 603

2021: 674

2022: 865

June 2023: 975

The brand added 13 markets since 20221 alone. Outside of North America, Popeyes opened 180-plus units in 2022, a nearly 7x increase above 2017 (when RBI bought the chain). From 2023 forward, China, Romania, France, Poland, South Korea, Indonesia, India, and New Zealand entered the picture, with other NCEs announce in Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Dominican Republic, Kazakhstan, and Taiwan. Referencing Siddiqui’s trip through these evolving markets, there are two distinct and digitally enabled designs currently deployed internationally, with a “bold new design” planned to roll out toward the end of the calendar.

Some key metrics to consider for NCEs since 2019:

Digital sales (percentage of systemwide): 75 percent

Kiosks: 100 percent

DSS: 90 percent

Modern image: 100 percent

So the Popeyes overseas is truly a forward-reflection of the brand. And it’s progressing fast. In March, Tims China, the master franchisee rapidly scaling Tim Hortons across mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau, announced it would spearhead growth for Popeyes as well. The company purchased PLKC International (Popeyes China), which held exclusive rights to develop and sub-franchise Popeyes in mainland China and Macau. Popeyes China brought $30 million in cash and Tims China said it would add another $60 million to accelerate development.

Important to consider in the grander scheme and what it possibly portends, Tims China opened its first coffee store in February 2019. By January 17 of this year, the 600th unit debuted.

“The whole idea is that as you look at chicken consumption all around the world, it’s the fastest-growing protein [per Euromonitor, chicken’s CAGR is projected to climb 7.3 percent from 2022 to 2027, into a $127 billion lexicon], and truly, there’s one dominant brand all around the world, but they’re very few global challenger brands in chicken,” Siddiqui says. “So we thought that was a big opportunity and as we think about our global model, a pretty big opportunity plug Popeyes into that.”

That global model: RBI has five offices with 320 people dedicated to international. There’s 2,600 accredited suppliers and 240-plus distributors.

International restaurants comprised about 45 percent of RBI’s total locations (30,125 total) and drive roughly a quarter of adjusted EBITDA across a predominantly franchise royalty driven business model. International represents 40 percent of the company’s consolidated systemwide sales, which total $40.8 billion. The landscape breaks down as 14,000 units through 120-plus markets and four brands (including Firehouse Subs).

Below shows the whitespace RBI’s brands, particularly Popeyes, have to chase. Just looking at Asia-Pacific, the gap between Popeyes and KFC is north of 15,000 restaurants.

Like the U.S., Siddiqui says it’s a matter of bringing Popeyes to the masses—a good problem to have. An opening in Manilla, he recalls, set a record for daily transactions. That was broken two months later with the brand’s first Shanghai store. Two months ago, Popeyes landed 40 minutes outside of London. That, too, set a fresh bar.

“When we enter these markets, Popeyes is just flying and it’s a massive, massive opportunity,” he says. “… We’ve entered 20 new countries in the last couple of years. And these are big markets. U.K., Spain, Mexico, India, these are billions of consumers, and we have less than 1,000 restaurants in most of these places. We can have hundreds, if not thousands more, in these markets over time.”