Restaurant jobs are demanding. They test one’s physical and mental stamina to a degree greater than many other professions. I can speak with authority on the subject: I’ve been in the business nearly five decades and have yet to work harder than during my years as an hourly employee and restaurant manager.

My first job was at an Italian full-service restaurant. On day one, I was planted in front of a two-compartment sink scrubbing pots and pans. I got an immediate lesson in how hard the work is. But just because the work is hard doesn’t mean that an employee will work hard. To be certain, I was raised with the belief that working hard and giving 100 percent effort is a matter of character, and that was reason enough to give it your best effort. After all, you should put in an honest day’s work for an honest day’s pay (no matter that it was $2 per hour under the table).

Soon after my introduction to the laborious task of scrubbing baked-on casserole dishes and crusted sauce pots, I set my first career goal: the salad station, a mere 8 feet away. My desire to traverse the ground between the sink and that coveted prep table reinforced the fact that working hard is a choice. Demonstrating that I was committed to excelling at washing dishes was a prerequisite to earning my way to the salad station. But I had to do more than just work hard. I had to learn. The more I learned, the more valuable I would be as an employee. And the more I applied my own initiative to learning about the role I aspired to, the better my chance of making it there.

But how was I to learn? The best insights I could gain into salad prep while my head was buried in the sink was to study the leftovers that came back to my station! And so it was at that very early stage that I learned an important lesson: observe the work of others, ask them questions, and apply what you learn in your own endeavors. Little did I know at the time that I had launched my first networking effort with my peers. Combining the values of hard work and continuous learning were important ingredients for personal achievement.

As my career progressed, I realized that the values of working hard and continuous learning are as vital to the performance of an organization as they are to the success of the individual. Of the two traits, working hard comes more naturally to the team, simply because of the nature of the business. Continuous learning, on the other hand, requires more deliberate planning and commitment, both on the part of the individual and the company for which they work.

Looking back, I recognize that I could have learned more faster. Much of what I absorbed during the early years came through passive observation of my peers and superiors—much like a child learning from their parents. When I joined Burger King Corporation in 1980, it was my first experience with an organization that approached training and development with great intention. Yet the nature of Burger King at that time—and I dare say many companies today—was to shelter their lower and middle management from outside influences. The learning that occurs in the workplace is often limited to the resources and viewpoint of the organization. An organization that keeps their employees in an insulated learning environment may not fare as well as an organization that encourages exposure to the broader industry (or other industries, for that matter).

In a perfect world, every employee at every level of the organization would have an insatiable appetite for knowledge. Wouldn’t it be tremendous if our biggest organizational challenge was satisfying that hunger? In some organizations, reality resides at the other end of the spectrum. People move from one day to the next, caught in the grind of working hard at hard work. We don’t stop often enough and ask our team members a simple question: “Is there something you would like to learn?” Curiosity is the most powerful of human characteristics, and it should be encouraged. Some managers operate on the opposite end of the spectrum. “Just do it” is the reply of a lazy supervisor. An organization that embraces the word “why” will outperform one that discourages it.

To advance learning to a higher degree, employees at all levels of an organization should be encouraged on three fronts.

1. Read. This month’s issue of QSR is a great example of a resource that offers insights into the factors that contribute to the success of a brand. It doesn’t matter if the content is about mainstream quick service or not; after all, the roots of the fast-casual sector extend back to the formula of combining elements from fast-food and casual dining. That didn’t happen by accident.

2. Develop a network of peers that is not restricted to people from within the organization. My personal development accelerated greatly when I reached the point that I was engaging with executives from other brands. In many organizations, this opportunity is reserved for people at the top of the ladder. If your concern is that your employee will be pirated, your organization has bigger issues. If your concern is about confidential information being unleashed, then school your team on what is permissible and what is not.

3. Allow and encourage your team members to be involved with your state restaurant association (and by extension, the National Restaurant Association). This will help them develop their peer network and expose them to insights not readily available elsewhere.

The above being said, it should come as no surprise that “work hard and learn” is an oft-repeated phrase at Firehouse. These behaviors are embedded in the culture of our organization. They shape our daily approach to the business. A lesson learned the hard way—by washing dishes.

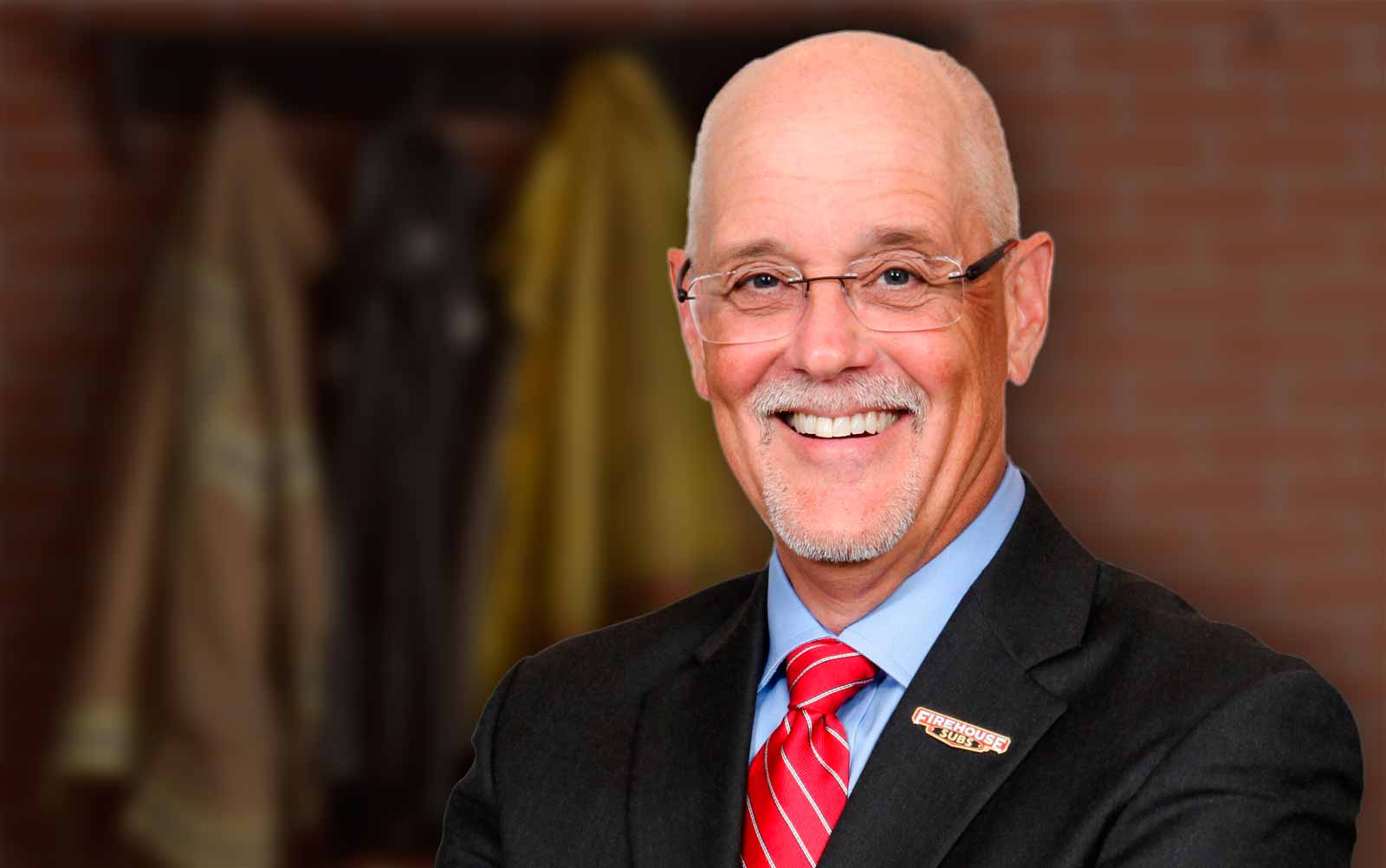

Don Fox is Chief Executive Officer of Firehouse of America, LLC, in which he leads the strategic growth of Firehouse Subs, one of America’s leading fast casual restaurant brands. Under his leadership, the brand has grown to more than 1,190 restaurants in 46 states, Puerto Rico, Canada, and non-traditional locations. Don sits on various boards of influence in the business and non-profit communities, and is a respected speaker, commentator and published author. In 2013, he received the prestigious Silver Plate Award from the International Food Manufacturers Association (IFMA).