BTIG analyst Peter Saleh prescribed to a popular narrative. That an industry-wide labor shortage is the result of high unemployment income, and people electing to wait out extended benefits instead of getting back to work. But he wanted to be sure.

So Saleh surveyed 300 unemployed people and asked why they’re not flocking back to hourly positions in restaurants, manufacturing, transportation, and the gig economy.

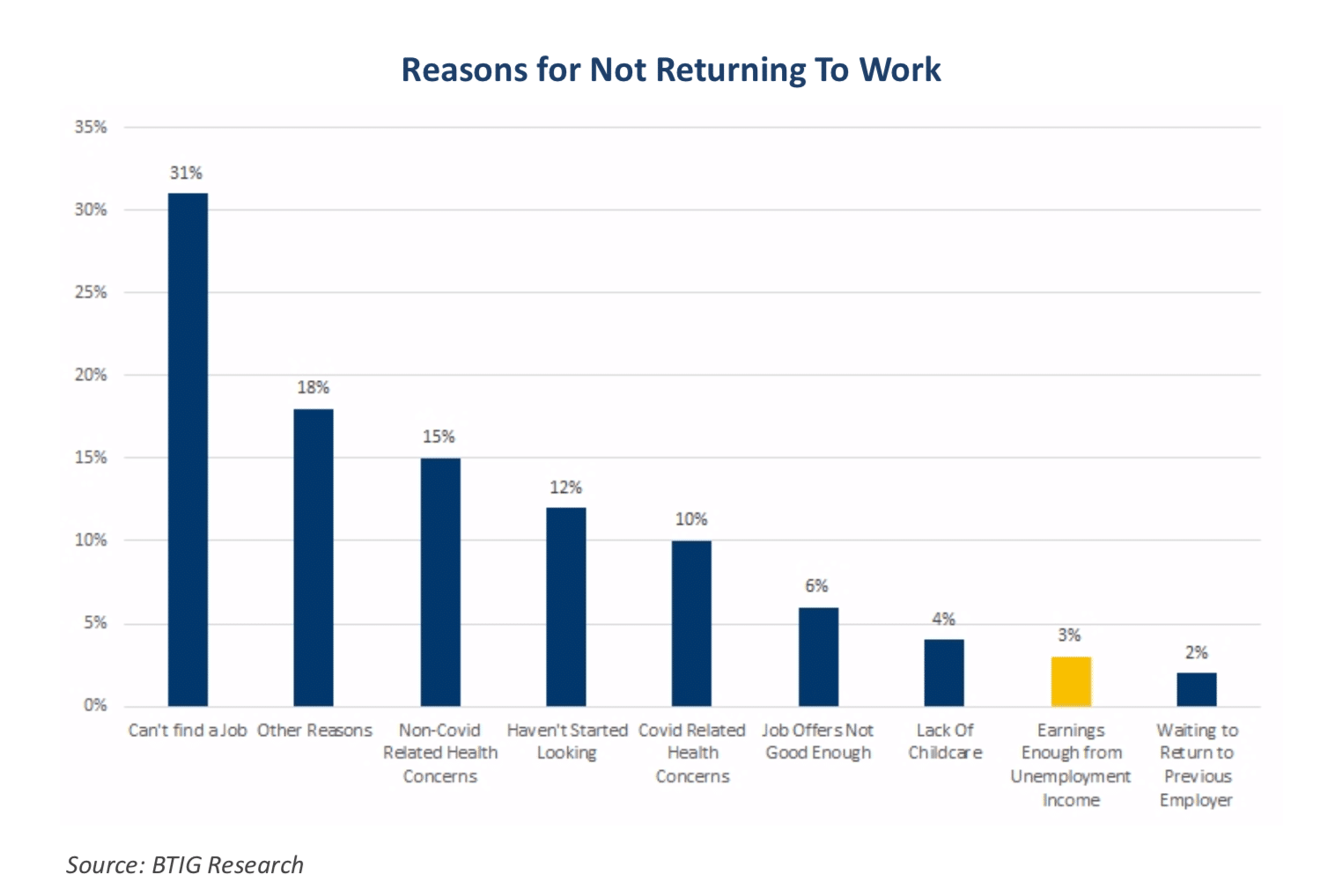

And just 6 percent said they’d be motivated to return when unemployment benefits expire, “far less than we had initially expected to see when we launched the survey,” Saleh says.

READ MORE:

What the Post-Pandemic Worker Needs from Restaurants

Will the End of Expanded Unemployment Really Fix the Hiring Crisis?

Inside the Restaurant Industry’s Critical Labor Shortage

What it could suggest is the labor dynamic for restaurants might not be as easy as circling a calendar date in September (the end of expanded benefits) and waiting for applications to roll in.

Interestingly, a summer hiring report from Snagajob returned nearly mirror results, with 4 percent of surveyed workers admitting they were waiting for benefits to expire.

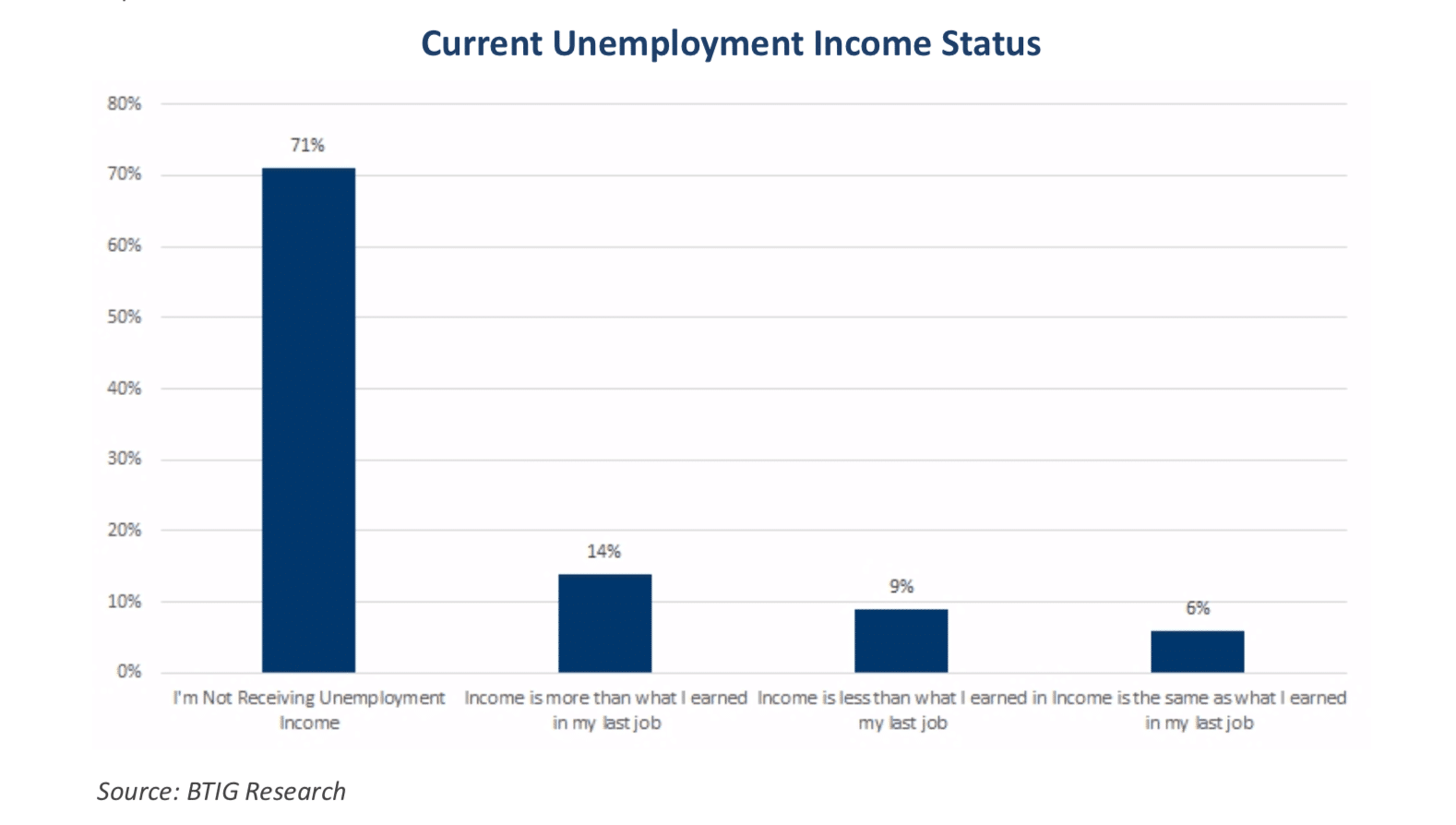

Only 3 percent of respondents in Saleh’s study said they were earning enough from unemployment income to stay on the sidelines.

According to a recent Bank of America report, American workers making $32,000 or less annually are better-served by unemployment under the current system. In other terms, the average person polled received $378 from their state in weekly unemployment payments. Add in the $300, and it’s close to $700 weekly, or $17.17 an hour for a 40-hour workweek. This is compounded, in many cases, by costs associated with taking care of someone at home, such as a child, when COVID sent routines virtual.

It’s a delicate line.

The conversation appears to be evolving, however, alongside market changes, Saleh says. And so is what hourly workers are looking for as their lives get back on track and demands readjust.

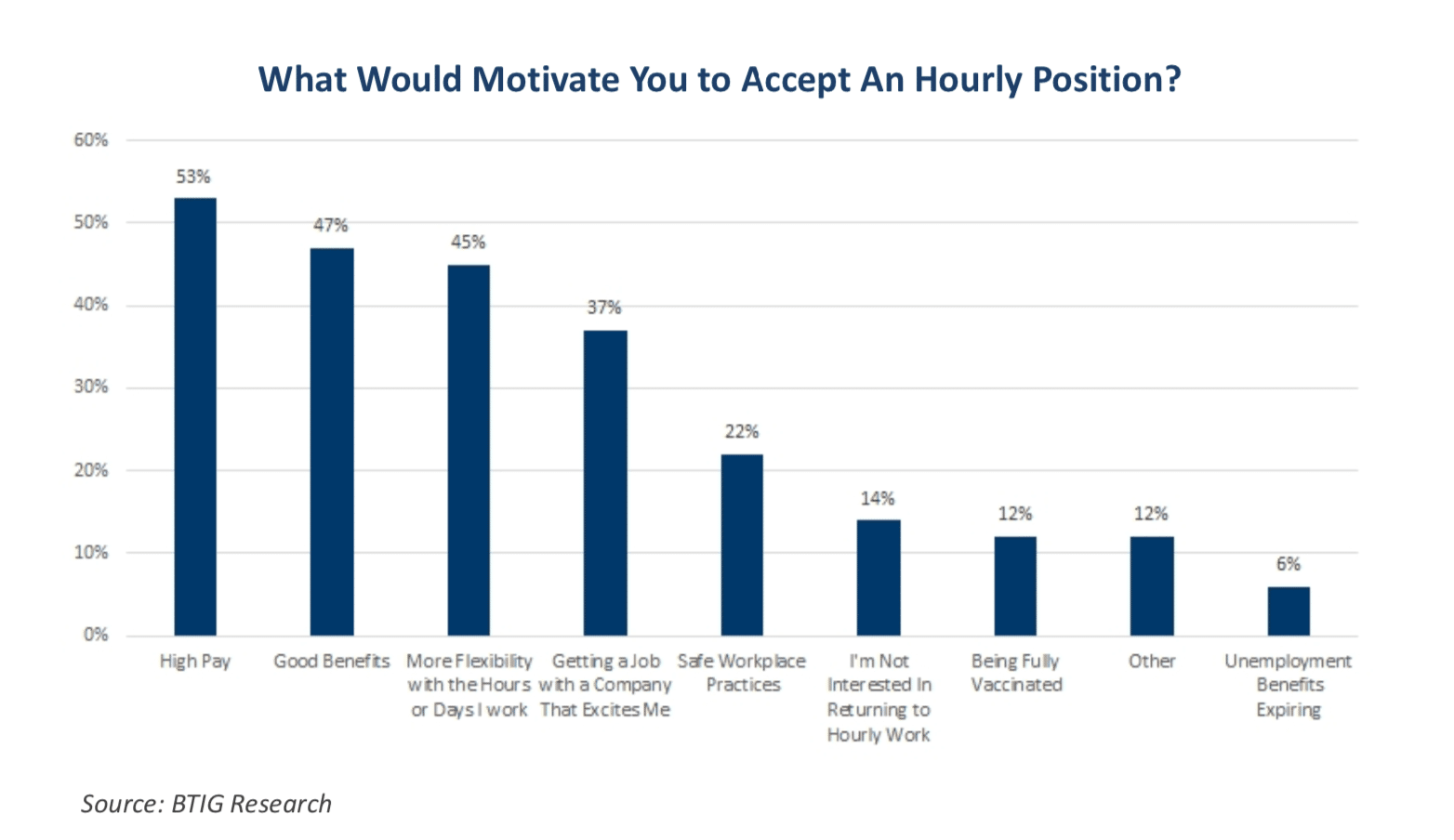

Forty-five percent said they were seeking greater flexibility with respect to when (days/hours) they work. This finding was consistent with commentary from United Natural Foods’ CEO a few weeks ago, as well as takeaways from BTIG’s Restaurant Tech Forum in late May, Saleh says.

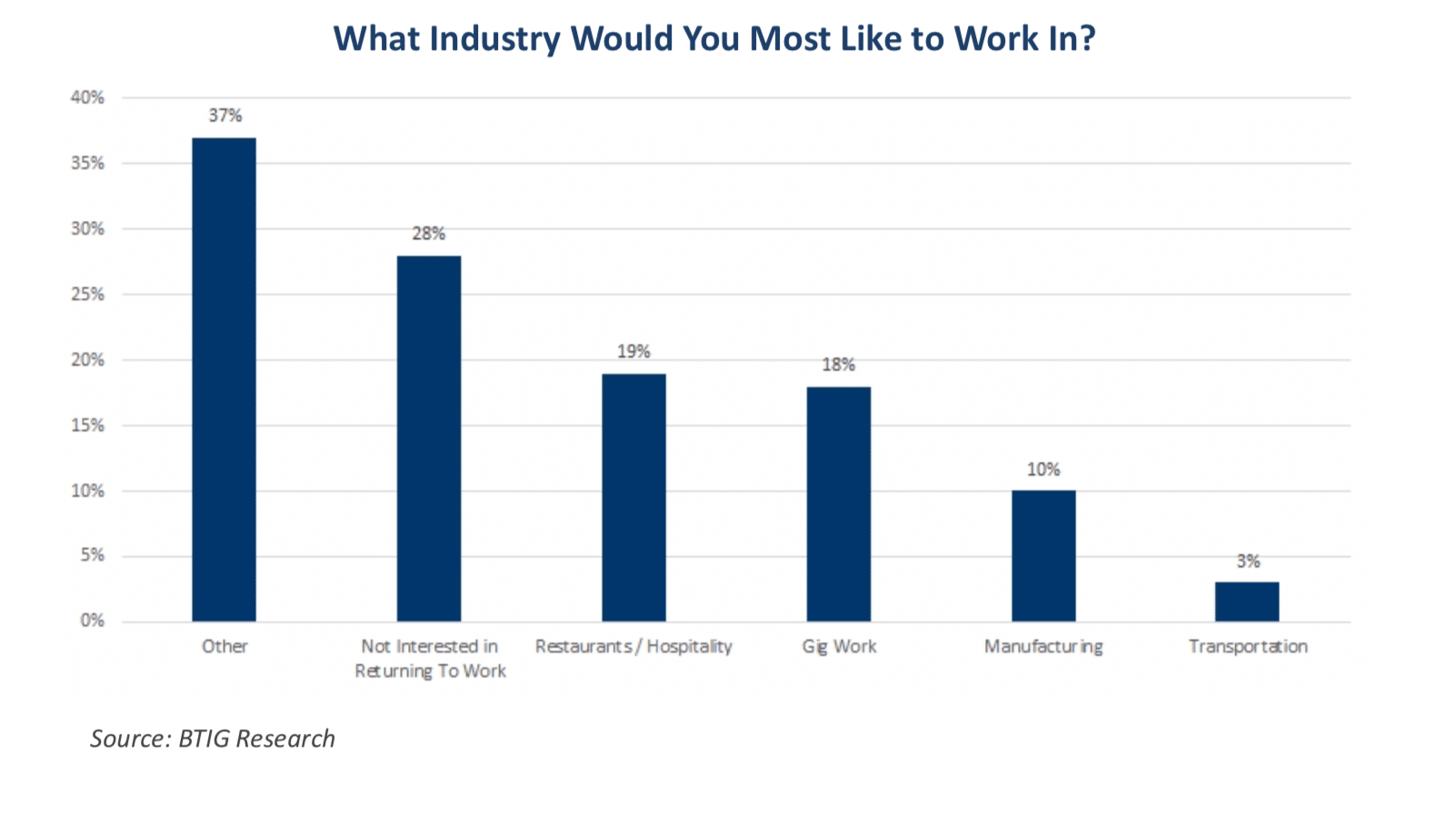

Also, 18 percent of candidates said they were now interested in gig-economy work, up from 11 percent pre-pandemic. That aligns with the notion people are searching for more work-life balance and control in regards to when and how they work. Restaurant employment proved fairly stable, too, with 19 percent of candidates indicating interest in the sector.

So how does this translate for the industry? Saleh believes many restaurants will have to boast larger rosters of employees working shorter shifts. “At least, this is the current environment that were in,” he says. “There are a lot of people who don’t want to come back to work and work an eight-hour day. Or work that overtime. I think you’re going to have larger rosters of individuals working shorter shifts, which means training costs are going to go up.”

Training for an hourly restaurant employee can run anywhere between $3,000–$4,000 per employee and up to $15,000 for managers, Saleh adds. He also thinks this means we’ll see “substantially higher” wages throughout the sector, as well as menu prices.

Let’s zero in on that latter point.

According to a recent study from Lisa W. Miller & Associates, 66 percent of guests were concerned restaurant prices were going to hike “a lot” in face of current pressures.

Likewise, when asked if guests are seeing signs of inflation and rising prices in general in the economy, 82 percent of people in a Datassential survey said they did. Thirty-five percent of those consumers said they’d cut back on restaurant meals if inflation accelerated. And 18 percent of people said they’d be fine paying a less than 10 percent menu increase to help restaurants navigate employee challenges. Once it got to 12.5 percent, however, the number fell off a cliff to 2 percent.

Saleh says the pandemic-driven imbalance between consumer demand and availability of labor is driving a spike in wages and commodity prices. While commodity prices should moderate once supply catches up with demand, wages and higher prices are a different story.

Typically, once wages tick up they don’t regress. Higher wages equal higher menu prices. And, in turn, inflation arises—the concern customers expressed in Datassential’s study.

Between 2015 and 2019, the average menu price increase, per Knapp-Track, was 2.4 percent, and 2.6 percent for the broader Black Box Intelligence benchmark. Saleh says he expects to see restaurant operators take multiple price increases this year and “blow right through that,” leading to effective pricing near 4 percent to offset higher wages.

And like wages, once menu prices go up, they generally stay there. LTOs and value menus might emerge, but restaurants seldom roll back prices en masse.

Chipotle, for instance, announced its goal to raise average hourly pay to $15 by the end of June, up from a current run-rate of $13 for all hourly employees, or 15 percent. It then followed by saying it would lift menu prices 3.5–4 percent to offset more than 300 basis points of margin pressure associated with the wage boost.

McDonald’s, too, said in May it was pushing pay for corporate hourly workers up by an average of 10 percent in coming months. Non-managerial workers would earn at least $11–$17 per hour, while supervisors would collect $15–$20 per hour.

Saleh expects McDonald’s to follow Chipotle in raising its menu prices—likely late summer/early fall—by “at least several hundred basis points” to cover the cost.

Historically, Saleh says, restaurant operators raise menu prices more aggressively when inflation is driven by wages rather than commodities. So once wages climb at category giants like McDonald’s and Chipotle, you can expect the rest of the industry to get on board, raise pay, and, in response, push menu prices higher across the quick-service lexicon.

Once more, higher wage and menu price increases aren’t flash-pan shifts; they’re permanent, Saleh says. “Setting a new, higher base, and implying that this inflation is not transitory.” “Restaurants don’t take their prices back down, they don’t take their wages back down,” he says. “I think this is all going to stick.”

Chipotle, in particular, Saleh says, has room to raise even further. “I still think there’s a lot of value in their food, in my view. They still have the opportunity to do that. They’re raising prices, and I think they’re one of the brands that I think people would want to work for over working at some of the other brands.”

Will the customer be open to higher prices? It’s a hard question to answer, Saleh says. Restaurants will always take a careful and methodical approach, gauge response, and leave room for flexibility. However, this is a unique climate.

Presently, it’s not so much a case-by-case conversation as it is an industry one. “Everybody is being impacted the same way,” Saleh says. “This is not regionally specific. This is not brand specific. This is all the restaurants, all retailers, anybody who uses hourly wages is feeling this pressure.”

Customers won’t see their favorite brand just raise prices. It’s going to be everybody at the same time, roughly the same amount.

“And so, as a consumer you’re not going to be going into Chipotle and be like, ‘wow look at those prices, they’re so much higher. Let me go to another brand and that will be more reasonable.’ They’re all going to do the same thing,” Saleh says. “It’s price increase across the board, all at the same time.”

The option will be: pay more for restaurant food, or try the grocery store. While that’s a possible disruption in the consideration set, Saleh says, his experience over the past decade-plus of covering restaurants is that when Americans are employed, they go out to eat.

“And that’s it,” he says. “They have more money in their pocket, they go out to eat and they spend money on food away from home. I think that’s just the reality. I just think we’re in for higher prices and, yeah, maybe there’s some pushback and some brands don’t have as much pricing power, but generally speaking, I think prices across the board are going up and there’s really not much more to it than that.”

Returning to labor realities, restaurants around the country have been forced to take drastic measures. While COVID restrictions loosened, many brands have still had to close dining rooms, shorten operating hours, and limit menu options. Only now, it’s not mandates tipping operators’ hand, it’s scarce labor.

A few weeks ago, SpartanNash said it participated in a job fair in Michigan, along with 60 other companies, hoping to fill 500 open positions. The job fair attracted only four candidates.

Sixty companies. Five hundred open roles. Four candidates.

Saleh and BTIG hosted a conference call with a veteran McDonald’s franchisee on the West Coast. The operator said dining rooms struggled to open due to the lack of labor, and, tangibly, the issue was amplified by male workers heading into construction jobs that offered higher pay than restaurants—a response to the housing boom, Saleh says.

These types of closures allowed operators, like the McDonald’s franchisee, to low labor costs by 100–150 basis points. And that might be a lasting change as chains target smaller footprints and leaner models.

This brings up a key point from before, and why the Bank of America data might not be so black-and-white. The concept unemployment wages nearly twice the rate of minimum wage would lead to artificially high unemployment is just one part of the story. Seventy-one percent of unemployed individuals in Saleh’s study said they’re not receiving unemployment income at all. Fourteen percent claimed the income they were getting from unemployment benefits was more than what they earned in their last job. And, again, only 3 percent said they were earning enough from unemployment income to not work.

For that thesis of expanded unemployment to blanket the entire debate, people, simply, would need to actually receive steady unemployment checks.

The advance number of actual initial unemployment claims under state programs, unadjusted, totaled 393,078 in the week ending June 19, a decrease of 14,720 (or –3.6 percent) from the previous week, per the Department of Labor. The seasonal factors had expected a decrease of 7,823 (or –1.9 percent) from the previous week. There were 1,447,127 initial claims in the comparable week in 2020. In addition, for the week ending June 19, 51 states reported 104,682 initial claims for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance.

During the week ending June 5, extended benefits were available in the following 12 states: Alaska, California, Colorado, Connecticut, District of Columbia, Illinois, Massachusetts, Nevada, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Texas.

A broader look, in May, the unemployment rate declined by 0.3 percentage point to 5.8 percent, and the number of unemployed persons fell by 496,000 to 9.3 million, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. These measures are down considerably from recent highs in April 2020 but remain well above pre-coronavirus levels (3.5 percent and 5.7 million, respectively, in February 2020).

Understanding who is unemployed:

- Among the major worker groups, unemployment rates declined in May for teenagers (9.6 percent), whites (5.1 percent), and Hispanics (7.3 percent). The jobless rates for adult men (5.9 percent), adult women (5.4 percent), Blacks (9.1 percent), and Asians (5.5 percent) showed little change in May.

- Among the unemployed, the number of persons on temporary layoff declined by 291,000 to 1.8 million in May. This measure is down considerably from the recent high of 18 million in April 2020 but is 1.1 million higher than in February 2020. The number of permanent job losers decreased by 295,000 to 3.2 million in May but is 1.9 million higher than in February 2020.

- In May, the number of persons jobless less than 5 weeks declined by 391,000 to 2.0 million. The number of long-term unemployed (those jobless for 27 weeks or more) declined by 431,000 to 3.8 million in May but is 2.6 million higher than in February 2020. These long-term unemployed accounted for 40.9 percent of the total unemployed in May

So there’s a lot to unpack in terms of what’s actually happening.

In May, the number of people not in the labor force who currently said they wanted a job was essentially unchanged over the month at 6.6 million, but was up by 1.6 million since February 2020. These individuals were not counted as unemployed by the BLS because they were not actively looking for work during the last four weeks or were unavailable to take a job.

Among those not in the labor force who currently want a job, the number of people marginally attached to the labor force, at 2 million, changed little in May but was up by 518,000 since February 2020. These individuals wanted and were available for work and had looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months but had not sought work in the four weeks preceding the BLS’ survey. The number of discouraged workers, a subset of the marginally attached who believed that no jobs were available for them, was 600,000 in May, little changed from the previous month but 199,000 higher than in February 2020.

If we’re talking restaurants, in May, employment in leisure and hospitality increased by 292,000, as pandemic-related restrictions continued to ease. Nearly two-thirds of the increase was in food services and drinking places (186,000).

But taking another look at why people are not returning to work, the range of issues is wide.

Fifty-three percent of Saleh’s respondents said higher pay would drive their decision to return to work. Forty-seven percent suggested good benefits would do so. In third, as previously stated, 45 percent picked flexibility as the unlock.

Mike Nettles, the chief digital and technology officer at Zaxby’s, recently highlighted the flexibility topic at BTIG’s technology forum. He said employee expectations shifted during COVID, and employers need to move rapidly through the hiring process, and engage candidates and employees more so with tech. Also, provide more of a gig-type job than the traditional quick-service restaurant position.

Saleh says the data suggests gig economy jobs are gaining in popularly, likely to the detriment of hourly positions. Ultimately, the higher training costs and larger rosters he referenced previously will end up on consumers’ bills (in the form of higher menu prices).

“You’ve got to provide a better working environment and more flexibility,” Saleh says. “You’ve got to attract more people to come and want to work.”