Sardar Biglari can get philosophical when reflecting on Steak ‘n Shake. In 2022, he shared a quote from Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo. “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block before I start my work. I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.”

Biglari’s point was the chain had to cut “superfluous elements” to sculpt a business model that worked. “We Michelangelo’ed Steak ‘n Shake,” Biglari said at the time.

Now, two years later, Biglari brought up American author Horatio Alger, who wrote of impoverished youths rising up, and how, in the late 19th century, his stories “captivated the public for the way his characters overcome adversity.”

“Our franchise partners are the flesh-and-blood Horatio Alger heroes of the 21st century. It is a reminder that when opportunity knocks, all one needs is a knack for seizing chances and for putting one’s all into the work at hand,” Biglari said in the company’s 2023 annual report.

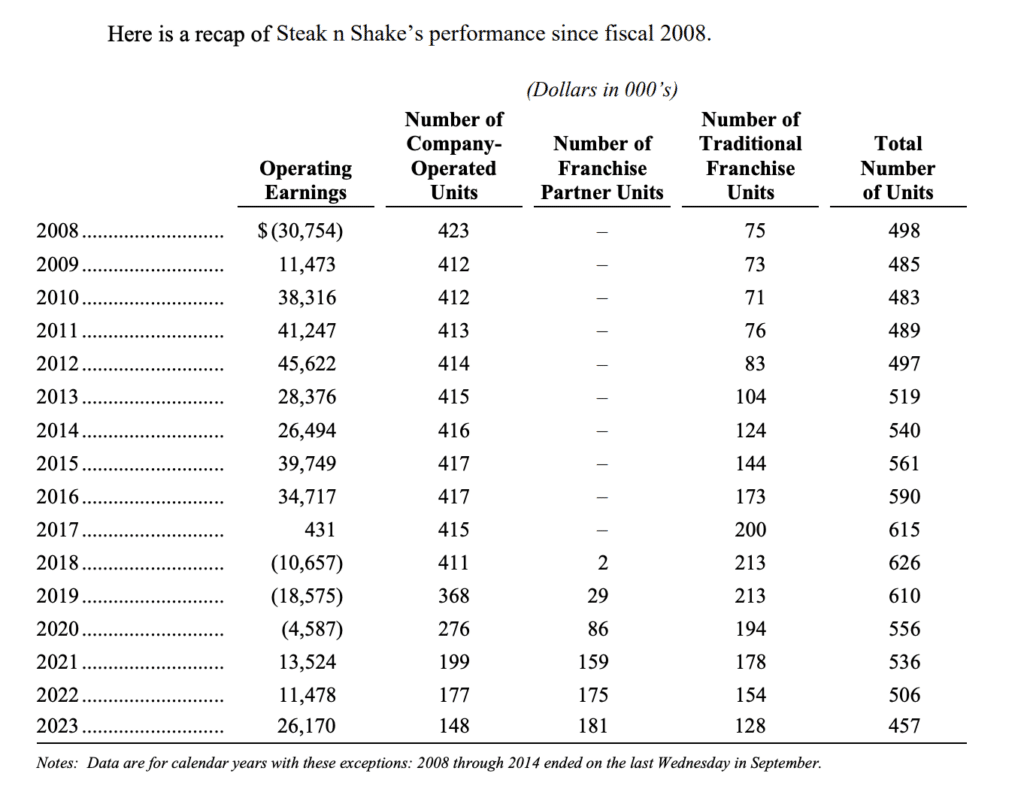

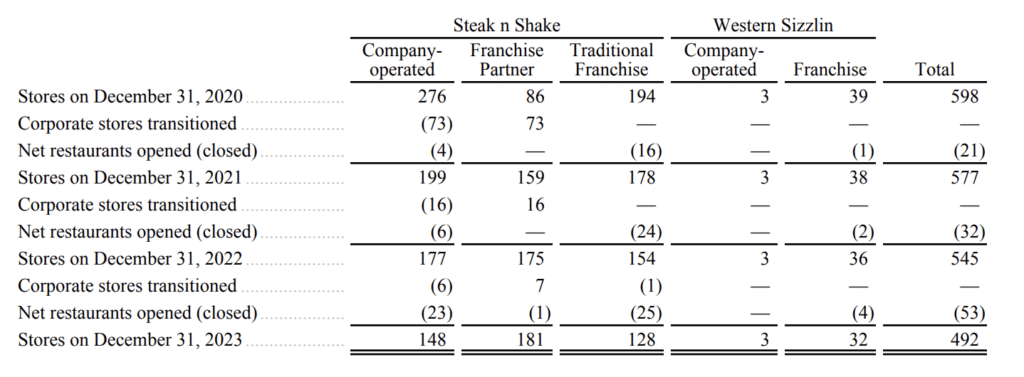

Historic texts aside, the reality for Steak ‘n Shake as 2024 marches on is a winding and complex story that’s seen the 1934-founded brand retract from 610 units at year-end 2019 to 457. That reduction of 153 restaurants includes closing 49 from 2022 to 2023.

Along the path, both the service model and ownership structure of the brand (what the Alger comparison was in reference to) has shifted dramatically at the store level. There were two “franchise partner” units in 2018, a term that refers to the company’s single-unit refranchising strategy that asks for $10,000 upfront in hopes of courting entrepreneurs to take over corporate locations. It closed 2023 with 181 of them, a net increase of six from the prior year. From the beginning of 2019 through the end of 2021, the program expanded at an average rate of 52 partners per year, but in the past two has slowed to 11. In 2023, Steak ‘n Shake had the fewest conversions yet, Biglari said, partly because it’s tightened standards, but also because the remaining company-run units have low sales volumes and marginal profits.

“Reversing the performance of these units will not be an easy task but we have dedicated the resources required to effectuate an upswing in their earnings,” he said. “The good news is that our best units are in the hands of our best operators.”

Meanwhile, Steak ‘n Shake’s company-run footprint has morphed from 411 to 148 during that window, inclusive of transfers as well as closures. And as of December, 17 of those 148 corporate restaurants were also temporarily closed, with plans to sell or lease 10 and refranchise the balance.

Additionally, the number of “traditional franchise” Steak ‘n Shakes declined from 213 to 128.

Reversing in time, Steak ‘n Shake was smarting off back-to-back yearly losses in 2020 when it charted this transformation. Yet really, it was a dynamic that began to slope four years earlier.

As Biglari has shared over the years, Steak ‘n Shake had $1.6 million of cash on hand, debt of $27 million, and losses of roughly $100,000 per day, when present management took control in August 2008. By the end of 2009, the brand was generating $100,000 per day.

But in 2016, same-store sales fell 0.4 percent and then 1.8 percent in 2017. They dropped 5.1 percent in 2018.

The number of customers declined from 116 million to 111 million to 103 million, which marked Steak ‘n Shake’s lowest figure in eight years. And for the first time since 2008, restaurants absorbed a loss in operating earnings at $25.8 (in dollars in 000s). As a company, it was negative $10,657. The number was negative $30,754 in 2008 before trending positive year-over-year until 2018.

So returning to 2020, it was evident Steak ‘n Shake wasn’t going to suddenly flip trajectory. That triggered a broad overhaul from full to self service alongside the implementation of Steak ‘n Shake’s new owner-operator program.

Biglari said, over the last three years, Steak ‘n Shake produced aggregate pre-tax operating earnings of $51.2 million. Or put differently, it’s back to generating profits.

“Admittedly, it is not a sign of strength for a business to repeatedly encounter emergencies that cause it to rise from the ruins, phoenix-like, stronger than before,” said Biglari, whose company also operates Western Sizzlin, Maxim, First Guard, Southern Oil, Southern Pioneer, and Abraxas Petroleum. “In future acquisitions, we will try to steer clear of businesses presenting multiple high-degree problems in a tough industry.”

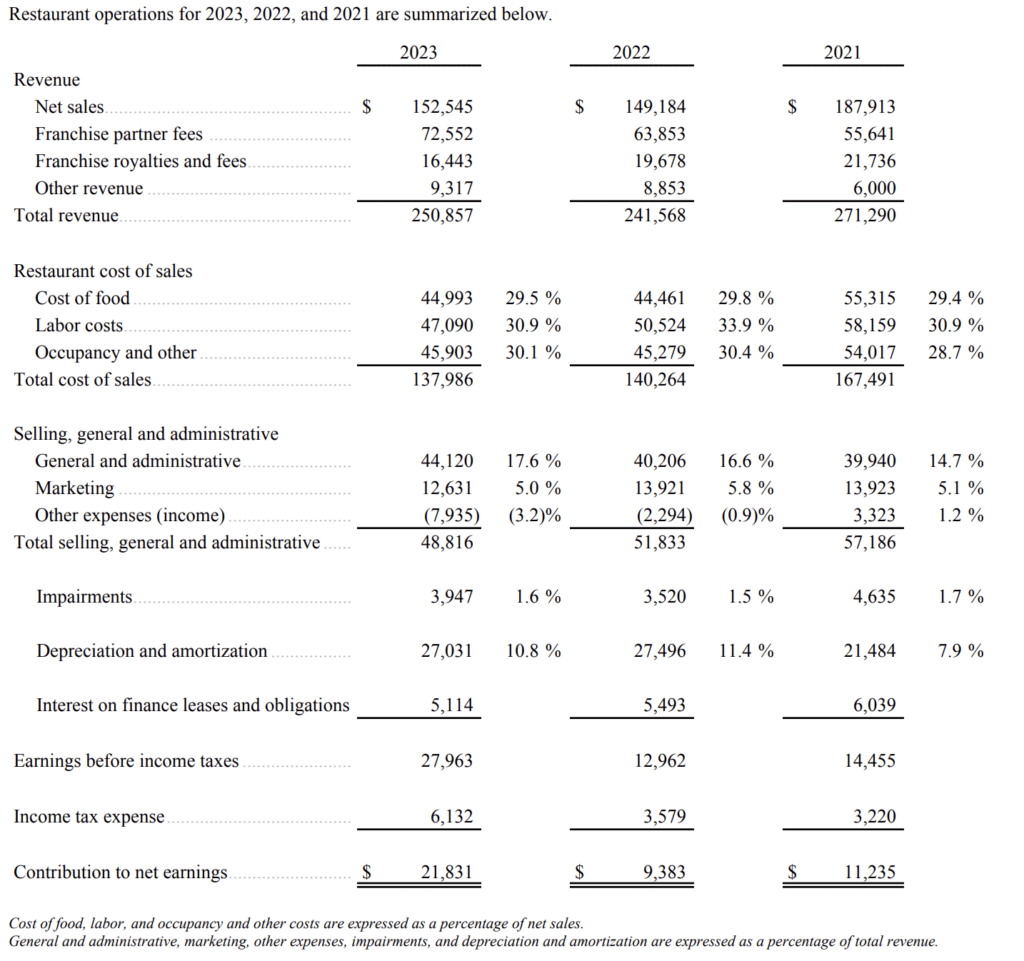

In 2023, Steak ‘n Shake produced pre-tax operating earnings of $26.2 million. The chain’s pre-tax cash return on capital was a “few percentage points short” of Biglari’s goal of 20 percent. To get there, the company expects to improve cash earnings and reduce investment in fixed assets.

On the asset discussion, Steak ‘n Shake made the call in 2020 to remove servers after 86 years of history and spent about $50 million to revamp everything from interior remodels to new point-of-sale to self-order kiosks. The chain also reduced operating hours and menu items.

Biglari said switching formats took Steak ‘n Shake’s breakeven point down by about 40 percent, “obviating our dependence on high unit sales to register a profit.”

As of today, every company and franchise-partner unit has been converted to self-service. Biglari did not mention if all traditional franchises followed suit.

He did share, however, that because of the wider change, “it will take some time to spur traditional franchise growth after several years of decline.”

“We are developing a new prototype that should inject verve into this segment and achieve satisfactory unit economics for franchisees,” Biglari said. “The traditional franchise business is an important dimension of Steak n Shake because the funding necessary to expand the brand is borne by third parties.”

Overall, Biglari said, Steak ‘n Shake’s transformation led to triple-digit gains in productivity. Under the prior approach, annual unit sales per employee, measured on a full-time equivalent basis, were about $64,000 in 2019. That was nearly $135,000 last year.

“With few exceptions,” store operating hours were reduced from 24 to 14 hours a day. Biglari noted overall sales per unit fell, yet sales per operating hour lifted by 50.7 percent.

At the same time, the average number of employees working per operating hour decreased by 28.5 percent.

“As a result,” Biglari added, “productivity grew 111 percent. The resultant cost savings have largely been passed on to customers through low prices, and to associates through higher wages.”

Biglari went on to explain he’s reviewed financial figures for all listed public owned restaurant companies in the U.S. (to note, Biglari held 2,069,141 shares of Cracker Barrel and 1,137,300 of Jack in the Box at year-end 2023).

“And the comparative changes in gross margin over the last few years should around your interest,” he said.

Since 2019, Biglari claimed, Steak ‘n Shake’s improvement in gross margin—namely, the profit after deducting food and labor costs as a percentage of net sales—has been better than that of every other publicly owned restaurant company.

The chain’s prime costs were 69 percent of net sales in 2019 and fell to 65 percent in 2023. “And yes,” he said, “we started out way behind the pack. But that 13-percentage-point improvement altered Steak ‘n Shake’s destiny.”

The classic diner-style chain isn’t done innovating. It’s in the process of adding face pay to kiosks where customers who opt in will have facial recognition technology available to hasten the process. Additionally, Steak ‘n Shake continues to upgrade drive-thru technology with new digital menuboards. “We will keep refining our operating system, from ordering to food assembly, to increase the speed of service while making our products more uniform,” Biglari said.

As for the single-unit operator part of the business, he added the company was “determined to rely on hundreds of enterprising operators to become the most productive, hospitable restaurant company in the industry.”

In some respects, it’s a model mirrored off the approach Chick-fil-A instituted to nearly 3,000 locations. Have one restaurant leader laser focused on the asset in front of them versus welcoming potential absentee ownership into the system. That was a pulsing problem for Steak ‘n Shake on the doorstep of 2020. Consistency was shaky.

“Although we set the standards for the brand and centralize such functions as purchasing and training, we also confer the authority to make operating decisions on those who have earned the designation of franchise partner, freeing them from layers and layers of bureaucratic control,” Biglari said of the new approach. “We have therefore structured the organization to achieve uniformity while building a culture of ownership at the unit level. For operators to think and act like owners, we believe they must be owners. In becoming a company of owners, we are changing the culture of the organization in our quest for service excellence.”

As mentioned before, Steak ‘n Shake today has more stores operated by franchise owners than the company. The goal has always been—and remains the case—to place all units in the hands of owner-operators, Biglari said.

To refresh, this franchise-partner agreement is hardly standard procedure. Operators make an upfront payment of $10,000 and the company pays for construction of the restaurant and its equipment. It assesses a fee of up to 15 percent of sales as well as 50 percent of profits. Biglari said Steak ‘n Shake generates most of its revenue from its share of the profits. “It is worth noting that with company operated units transitioning to franchise ownership, Steak ‘n Shake will appear to be a much smaller company than before from a revenue perspective but not from a profit perspective,” he added. “Accounting convention dictates that in company-operated units, sales to the end customer are recorded as revenue; but for franchise partner units, only our share of the restaurants’ profits, along with certain fees, are recorded as revenue.”

The language can get a bit jumbled, but the essential point is the system resembles a federation of legally and administratively separate enterprises. Fees generated by franchise partners were $72,552 during 2023 as compared to $63,853 during 2022.

Again, though, Biglari believes it’s a model that fosters a culture where franchisees “display a consummate commitment to their respective restaurants.”

“Absentee ownership is neither desired nor permitted,” he said.

These franchisees are responsible for managing day-to-day operations, setting wages, and “building their business one customer at a time.”

As Biglari touted throughout recent years, he said these owner-operators can “earn considerable sums.” Over the last four, the average franchise partner made about $137,000 per annum, “which was more than the average accountant, architect, or engineer in America earned,” Biglari said. “But make no mistake: We are not minting millionaires but are merely providing the means—they are earning every penning.”

That element is what inspired his Alger reference. At year-end 2023, minority- and woman-owned businesses accounted for 63 percent of all franchise partnerships, while Black-owned enterprises represented 21 percent.

“We did not set out to win any diversity awards; nor did we ever develop a diversity program. The word ‘diversity’ is frequently used to force an outcome,” Biglari continued. “The goal is laudatory but it often misses its mark. We simply focused on individual skills and effort, and it resulted in a diverse group of immensely industrious and ambitious owner-operators. We will continue to search for talent, not diversity, and by getting the former we will end up with the latter, not the other way around. Our system of meritocracy is about placing the right people into positions of power and ownership.”