Shake Shack has more stores under construction than it ever has at 35 locations. It’s blueprinted across 10–15 drive-thrus, walk-up windows, core builds, food courts, and further disruption of real estate historically shadowed by fast-food giants, like roadside pull-offs and stadium venues.

In 2023, the fast casual anticipates 65–70 total openings, about 40 of which will be corporate run. Even with delays, from the availability of kitchen, electrical, and HVAC equipment to permitting and landlord lead times, which CEO Randy Garutti called “probably our biggest headwind to overall sales growth,” Shake Shack is knocking on its biggest spurt yet.

However, the path forward has new and familiar bumps. One, in particular, Garutti said.

“Now, how the heck do we staff these Shacks—this is the hardest thing going on right now,” he said Thursday during a conference call.

There’s a Shake Shack coming to Baton Rouge, Louisiana, in Q4, which marks another fresh market. So the brand is flying people in and keeping them there “for a while” to get it going. There are others in the Bay Area where Shake Shack has had to bring employees from other regions to build up management. “With the challenges of staffing it’s just harder right now at all levels,” Garutti said. “And we’ve got to kind of move our talented teams around a little bit more.”

Shake Shack’s Q3 same-store sales climbed 6.3 percent, year-over-year, as total revenue lifted 17.5 percent to $227.8 million. Systemwide sales, anchored by expansion, rose 18.3 percent to $353.2 million. As sales have continued to widen, however, Shake Shack remains understaffed to optimal levels. It’s impacting the chain’s ability to be open full hours consistently across all channels and reach desired throughput.

Garutti said Shake Shack has “never been more innovative” in its recruitment, especially in regard to the first 30 days of employment. In some locations, with Shake Shack’s new tipping availability, employees are earning north of $20 per hour. The company just graduated its sixth class of employees through its Shift Up program, which serves as a pipeline for hourly workers to elevate to managers and map a career ladder.

But the effort is centralizing within stores as well. Today, roughly half of Shake Shacks offer kiosks. The brand said Thursday it’s committed to retrofitting all locations by the end of 2023.

CFO Kate Fogertey said kiosks are Shake Shack’s most profitable channel and produce the highest in-store checks. Units with kiosks also boast better labor utilization rates than those without.

By the end of 2022, about 20–30 existing stores will have added kiosks, leaving 60–70 in line for 2023.

Broadly, Fogertey said, kiosks represent a “really great lever” for Shake Shack to lean on to help streamline labor and address the front-of-house opportunity. She added a good portion of guests prefer them over traditional cashiers when given the choice. In many locations, Shake Shack has five or six kiosks alongside one or two cash registers. “And you see a number of people … instantly go toward the kiosk,” Fogertey said. “If you haven’t used one before, I highly encourage you do.”

Beyond labor, customers appreciate the ability to sit with the menu and page through, she noted. Shake Shack sees that translate through orders as they tack on premium offerings. Guests will view LTOs and navigate order flow with upsell throughout. “We’re having a burger, we’re going to have our shake and our fry and our lemonade,” Fogertey said. “And they can visually see all of that.”

From a labor and check perspective, it’s definitely accreditive, she continues. So the benefit is clear: in some instances, Shake Shack can run leaner still meet guest expectations. But also, the brand can take extra labor and dedicate it to more value-added tasks, like expediting orders or greeting guests walking in.

Garutti said Shake Shack has elected to take this approach, at least for now, over exploring robotics or automation. “Today, I’m excited for it in the future,” he said. “I don’t think it’s the best use of our time to be frontrunners on that, and we’re watching closely. We continue to meet with interesting companies who are doing that work and seeing how it could impact us. But I think we’re a little way away from seeing something like that in a Shack right now.”

Instead, the horizon will center on employee productivity and format evolution. Drive-thru, for instance, is something Garutti admitted is going to be an expensive road out of the gate. There are currently six operating today, with three to four planned by year’s end (Michigan, Ohio, and the Baltimore area among landing spots), and, as noted, 10–15 on deck for 2023. Garutti said Shake Shack is encouraged by the early operational flow and performance. And it’s a work in motion. “This is the right place to focus additional capital right now, with the goal of unlocking a larger total addressable market,” he said. “I believe in the next year, as we get a strong class of drive-thrus and we learn more about the real estate, design and operational decisions we’ve made, will have a much clearer view on the size of the prize.”

Garutti expects the drive-thru learning process to take time for Shake Shack. Of the first six, there are multiple kitchen flows, external and internal designs, and varied ways the brand simply moves food through. Not to mention, “very different real estate decisions,” he said.

“With the next three or four that opened by the end of this year, we’re going to learn all new things,” Garutti said.

Thus far, Shake Shack has taken stock of things like learning how much space it needs for cars and what peak hours look like; how best to take orders and when it’s wisest to put order takers outside. “We are honing in a lot better on how we think the kitchen flow should work so we can protect and maintain the premium ingredients that we serve every way,” Garutti added. “We’re learning what menuboards should look like. How big they should be and what kind of things sell. When we put shakes up there they sell, right? So what should we do about that? It’s vast and it’s really a totally different model.”

The high-level feeling, though, is optimistic, which is why Shake Shack will continue to open its CapEx coffers. “We think we have a dynamic, really cool product out there with our drive-thru,” Garutti said. “We think there can be lots of them. But we’ve got a lot of work to do to optimize that, and that’s going to happen over these next few years.”

“I think it’s a huge opportunity for us to keep being who we are in traditional places where the opportunity is vast,” he added. “That is what drive-thru is about. It’s what our expansion of these categories [such as roadside and stadiums] can be all about. And I think, we can continue to do it so that, the next generation of burger leaders, like my kids, has a higher expectation of what they should get.”

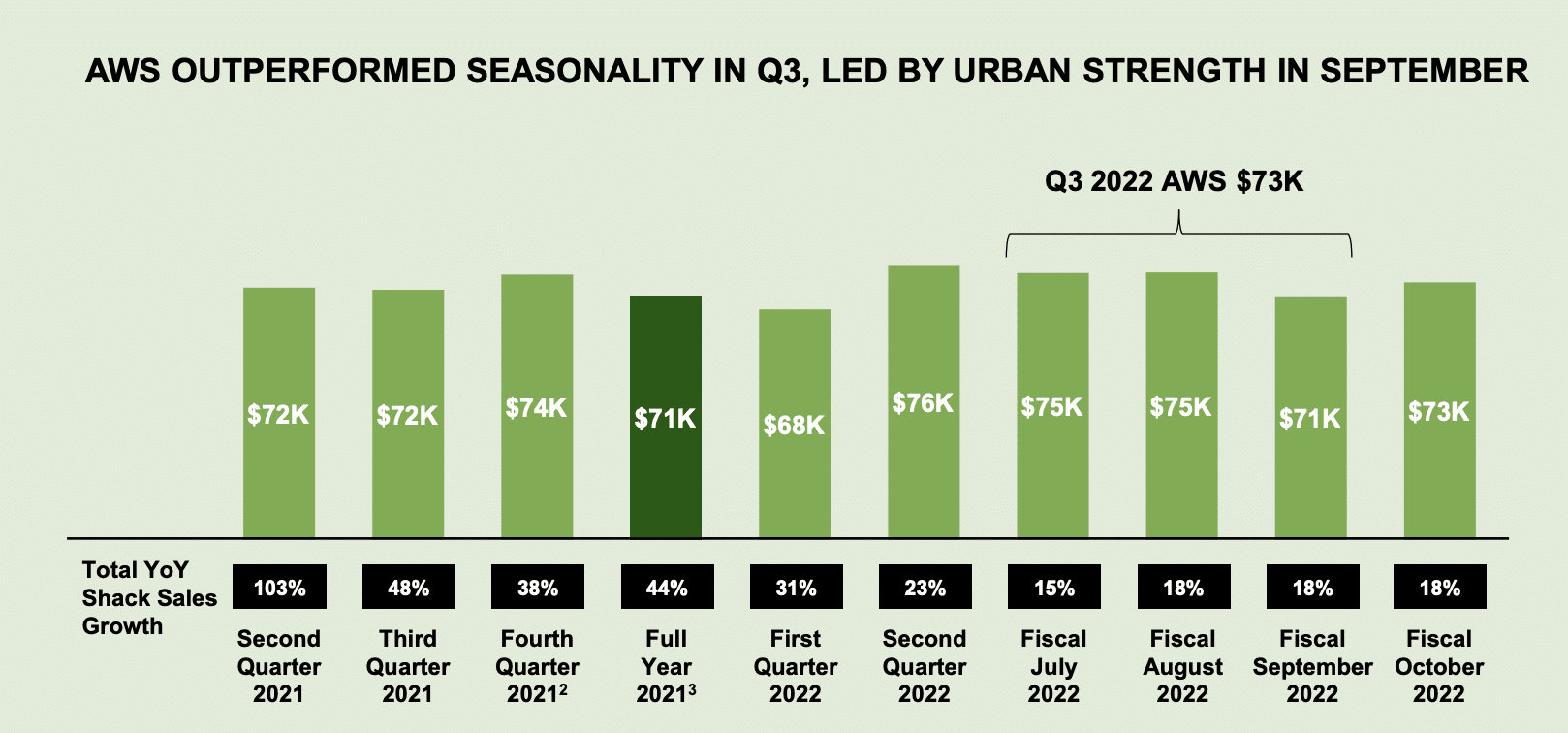

Shake Shack’s Q3 average weekly sales clocked in at $73,000 as it maintained a trailing-month AUV of $3.8 million.

The fast casual’s 6.3 percent comp featured 2.9 percent traffic growth and 3.4 price/mix. It held mid-single digit price in the quarter—6 percent inclusive of a March bump (3.5 percent) and different premiums across channels, like delivery—with in-store sales (and more single orders) expanding as the pandemic’s impact on routines ebbs. Generally, Shake Shack said, more guests are ordering in smaller groups and solo transactions compared to 2020 and 2021. Items per check trends in cold beverage, fries, and shakes stayed elevated.

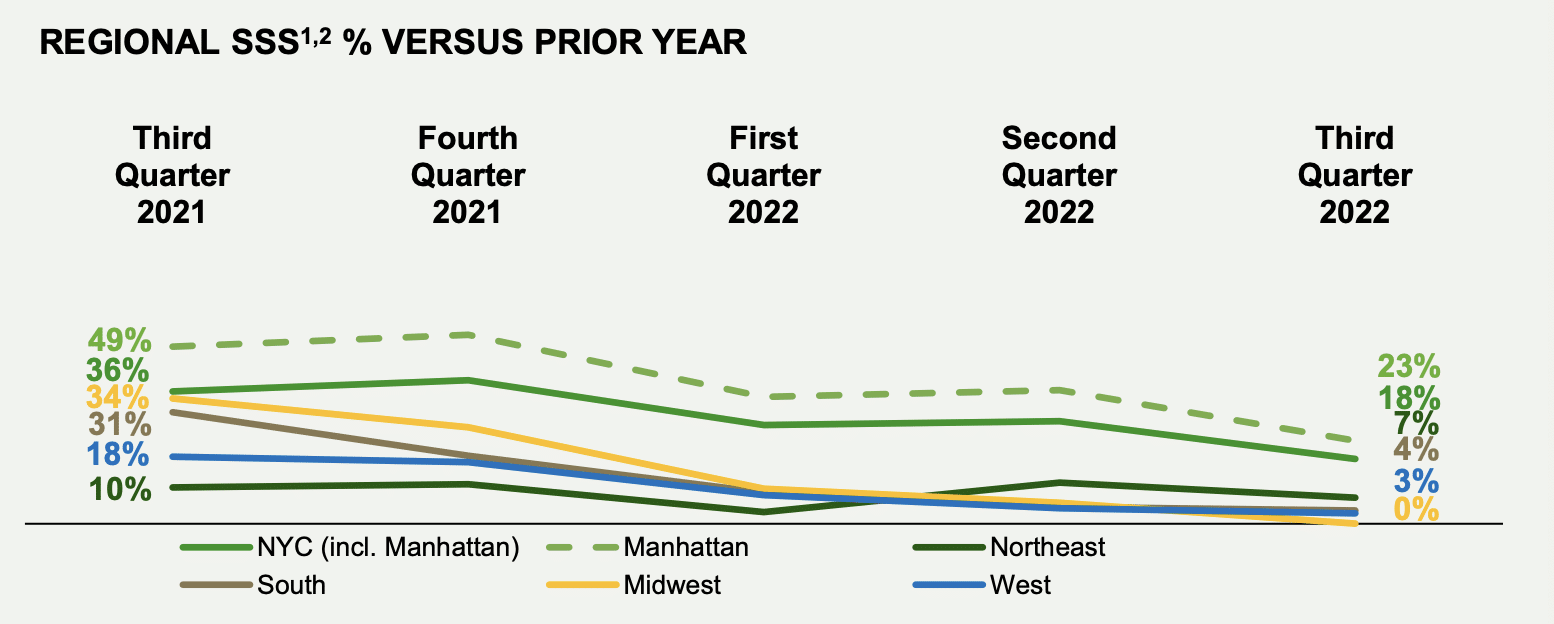

Shake Shack’s urban same-store sales hiked 11 percent in Q3. After Labor Day, the brand said urban centers picked up traffic compared to recent years. Units in urban transit centers generated more than 60 percent same-store sales growth in Q3. Suburban locations bumped 2 percent on the top-line.

Manhattan same-store sales were 23 percent higher.

Led by price and urban market traffic, October same-store sales at Shake Shack upped 8.3 percent, year-over-year. There’s been a wide chasm of price, anywhere between 2 and 10 percent across tiers (for a blended 5–7 percent in mid-October).

All in, Fogertey said, the brand’s burger, fries, and beverage combo still runs, typically, less than $14, “well within and often priced below the cost of other lunch or dinner options nearby.”

Shake Shack expects to maintain a blended high single-digit price across channels into 2023.

The company reported store-level operating profit of $35.8 million at a 16.3 percent margin—a slight uptick of 50 basis points versus last year, even with inflationary pressures weighing. Shake Shack swung an operating loss of $4.8 million and a net loss of $2.3 million on adjusted EBITDA of $19.5 million.

“On the profitability side, prior to the COVID inflationary impact of the last few years, we outperformed our long-term targets of 18 to 22 percent op profit at the Shack level,” Garutti said. “While many of our current Shacks beat these targets, on average this is a number we’re not consistently hitting today. But we continue to believe it’s the right long-term target and one we can return to.”

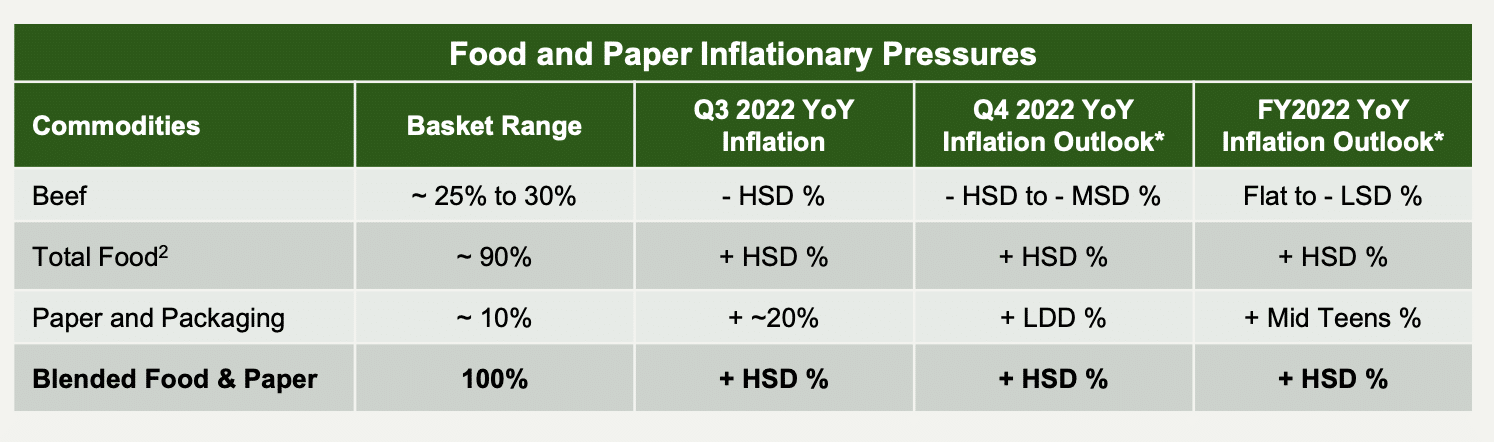

Fogertey noted Shake Shack’s food and paper costs surged high-single-digits year-over-year—they were $67.8 million or 30.9 percent of sales—and utility costs are nearly 25 percent higher than last year. Dairy costs were up nearly 30 percent, led by butter, cheese, and custard. Fryer oil costs rose materially as did fries and paper and packaging costs grew nearly 20 percent, year-over-year.

Shake Shack’s growing digital business hasn’t let up. In Q3, it grew its digital app purchasers by 40 percent, year-over-year. Since March of 2020, Shake Shack has gathered more than 4.5 million unique first-time digital app purchasers.

Fogertey said the chain continues to build its base with marketing initiatives, such as offering its limited-time Hot Ones menu to its digital users first and other promotions that focused on digital-only dayparts.

Shake Shack’s digital guests spent on average 25 percent more per visit than non-digital users in Q3, and digital mix was 36 percent of sales.

“More of our guests are enjoying us through our omnichannel experience finding us both digitally and in-Shack,” Fogertey said. “This is a good thing for the long-term growth of our business.”

Balancing digital’s elevation with dine-in is an act that comes back to the opening one. Garutti said most of Shake Shack’s gains owe to four-wall diners in recent quarters, which fits given where the biggest plunge took place. It shows consumers are returning. “People want to hang out of Shake Shack and want to come in there and hang out,” Garutti said. “With that you’ve got just a return to increased foot traffic and how things work in the Shacks on top of the digital channels that never existed a few years ago.”

“So we’ve got to get better,” he continued. “It starts with staffing. We’re not staffed everywhere all the time where we want to be … Where we are, we are very self-aware and a lot of it begins and almost always ends with being fully staffed. That’s what it’s about.”

Like all restaurants at this turn in the COVID story, Shake Shack is evolving from the ups-and-downs of a market there was no playbook for. That includes 40-year-high inflation. But now, you’re operating with digital pickup, aggregators, and other flow factors that aren’t sliding in usage.

“And so much of our focus has been on digital and will remain there, but as people return, it’s another call to action for us to just get in our restaurant and be relentless about how we execute,” Garutti said.