“To be honest, I thought they were calling to sue me.” Those were the words of Kim Sánchez, owner of Sweet Dixie Kitchen, a trendy brunch spot in Long Beach, California. By now, Popeyes’ chicken sandwich, and the social media eruption that followed, has buried news across the fast-food lexicon. Including where this crazy story actually began from a marketing standpoint.

Back in 2017, Sweet Dixie Kitchen grabbed notorious headlines when it got caught serving Popeyes chicken and presenting it as their own. Sánchez was spotted walking through the front door with Popeyes bags. It went viral overnight and sparked the #POPEYESGATE backlash.

Popeyes playfully engaged the restaurant to introduce its new chicken sandwich—the company’s biggest product launch in 30 years (and that was true before it even hit stores)—from August 8–9 ahead of the August 12 rollout.

“If you want to try it, be sure to pay them a visit on August 8 and 9. We promise our new sandwich is worth the visit,” Bruno Cardinali, head of marketing for North America for the Popeyes brand, said in an earlier release.

If only he knew. The buttermilk battered and hand-breaded white meat chicken filet, served on a brioche bun with two barrel-cured pickles and mayo or spicy Cajun spread, exploded like branding Pop Rocks. A social battle with Chick-fil-A ensued and other brands dove in. Lines snaked around buildings. Some restaurants ran out of product. Others didn’t have enough buns. “Be back soon!” signs hung on windows.

On Tuesday, Popeyes announced via Twitter that the sandwich sold out, two weeks after launch. “We love that you love The Sandwich,” the company said. “Unfortunately we’re sold out [for now].”

Y’all. We love that you love The Sandwich. Unfortunately we’re sold out (for now). pic.twitter.com/Askp7aH5Rr

— Popeyes Chicken (@PopeyesChicken) August 27, 2019

According to Business Insider, Popeyes said it sold as many sandwiches in that span as it expected to hand out through the end of September. It didn’t provide a timeline for when the item might return.

“We, along with our suppliers, are working tirelessly to bring the new sandwich back to guests as soon as possible,” the company told BI.

… y’all good? https://t.co/lPaTFXfnyP

— Popeyes Chicken (@PopeyesChicken) August 19, 2019

International Business Times, citing “various sources,” said Popeyes earned anywhere between $20–$23 million from its new chicken sandwich, and the buzz that followed.

Apex Marketing Group estimated Popeyes’ garnered $23 million in equivalent ad value across digital, print, social, TV, and radio in the 11 days that followed August 12.

READ MORE:

CAN POPEYES BECOME ONE OF THE WORLD’S FASTEST-GROWING BRANDS?

WHAT DOES IT TAKE TO WIN THE CHICKEN WARS? AND WHY IS CHICK-FIL-A NO. 1?

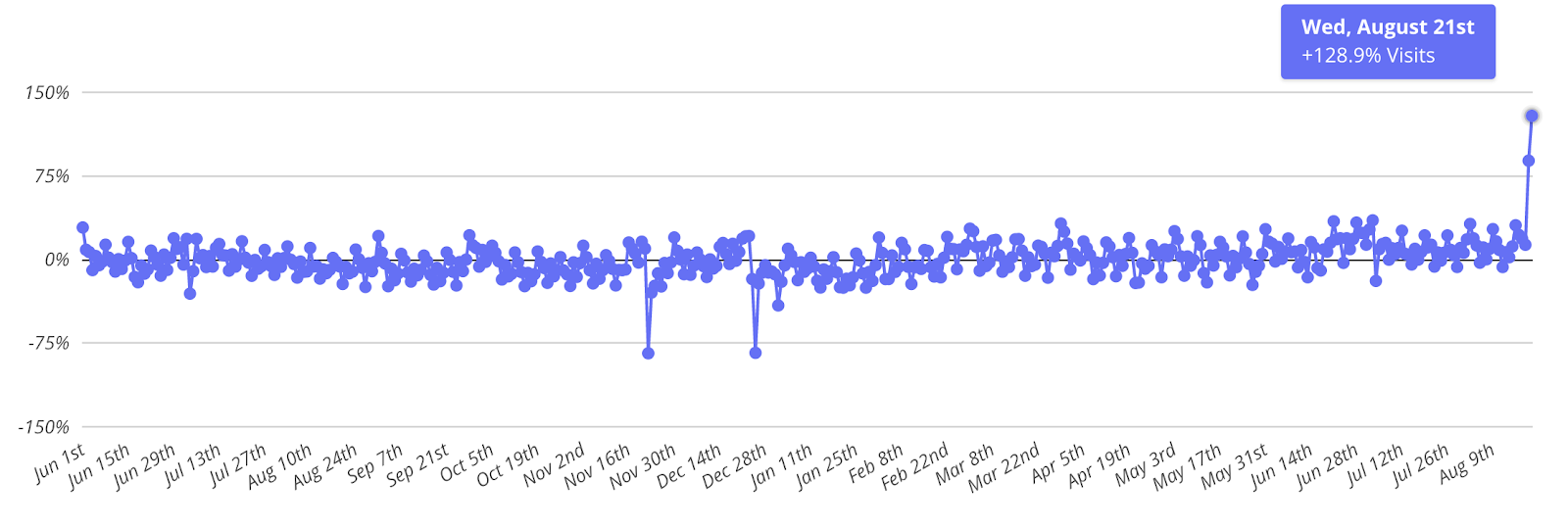

Placer.ai, a mobile location analytics platform, took to its foot-traffic data to see how this social storm translated to action and direct results. The info was pretty compelling.

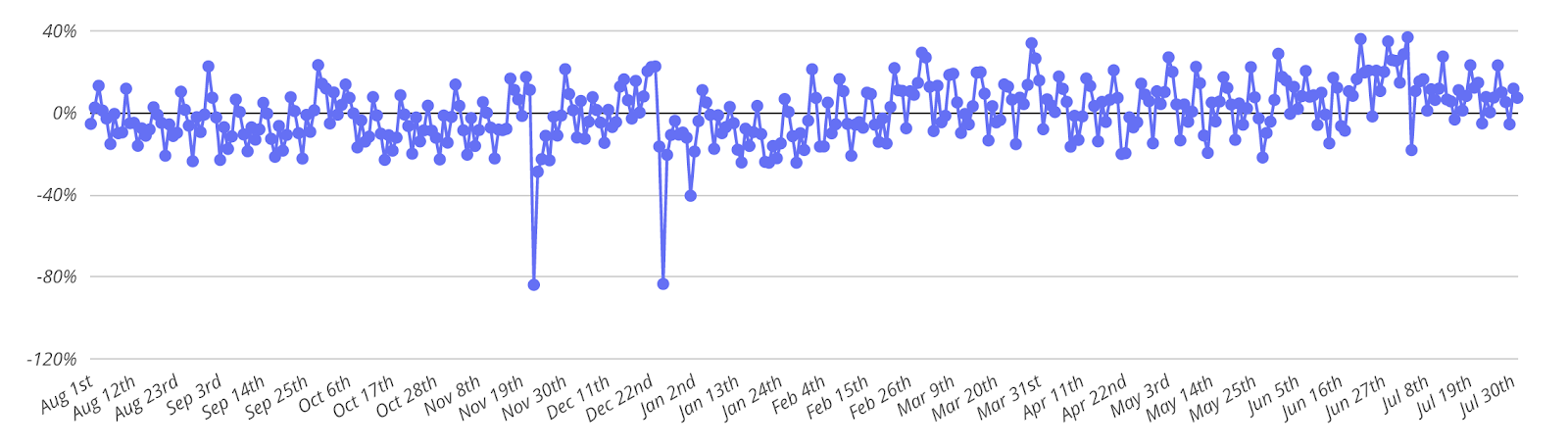

Looking at the baseline, Popeyes’ restaurant visits over the 12-month period between August 2019 and July 2019 showed consistent and sustained growth. June looked particularly strong.

But, typically speaking, August is not a robust stretch for Popeyes, with 2018 seeing visit rates consistently dropping below the period’s baseline and 2019 numbers trending down toward the end of July.

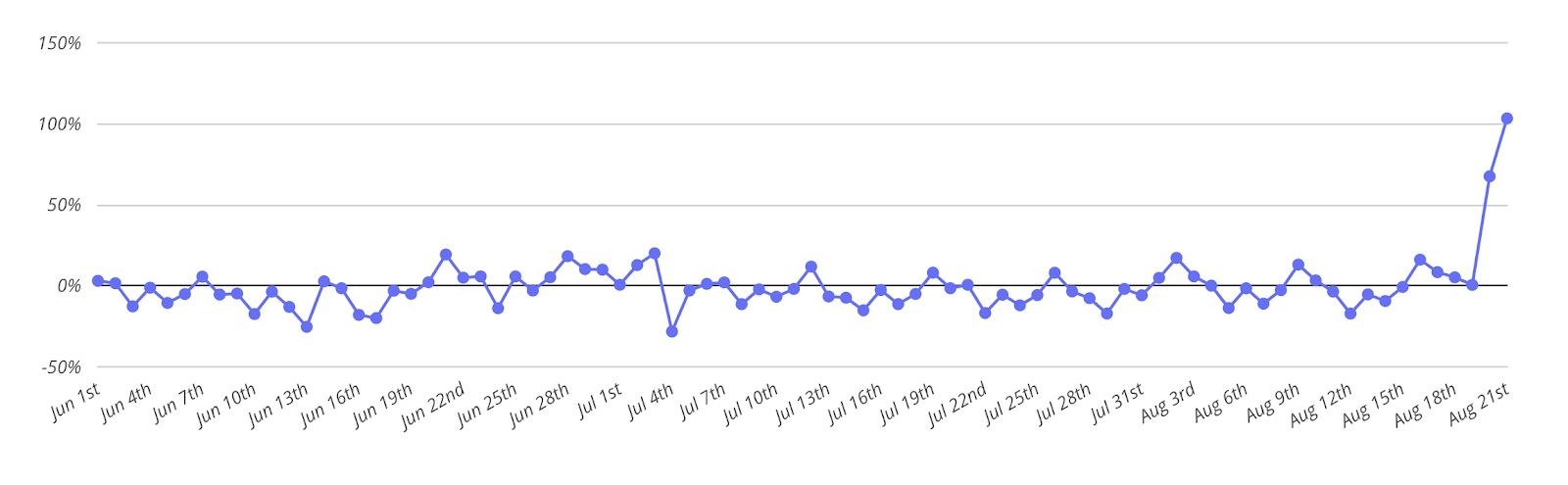

Not a bad time to try something a bit out there then, right? On August 20 and August 21, traffic to Popeyes branches nationwide rose a staggering 67.6 and 103.3 percent, respectively, above the baseline for the summer thus far (June 1 through August 21). As Placer.ai puts it simply, “this is an outrageously high peak.” And it proves that the buzz wasn’t restricted just to social sites. This marketing boom pushed people out of the house and into a location.

What’s intriguing is how the product’s marketing morphed into something past simple commentary. The battle between Popeyes and Chick-fil-A led people not just to chime in, but to actually go to the restaurant and post photos of themselves eating the chicken sandwich.

Popeyes tapped into what social media does best (for better or worse)—it turned everybody into a star or critic in their own mind, on their own platform. The brand managed to extend beyond developing a buzz-worthy product into creating one that demanded direct action.

Customers didn’t need to see it for themselves; they had to tell everybody about it. It was almost like the Pokémon GO of fast-food promotions. Popeyes more than created content, it nurtured content that connected users, and thus fed itself (is still feeding itself).

But let’s go a step further and examine how Chick-fil-A compares. This, of course, is about as golden a measuring stick as exists right now. The brand posted systemwide sales of $10 billion last year across 2,400 restaurants. How impressive is that? Only five restaurants in the country crossed the $10 billion figure last year, according to the QSR 50.

But here’s a look at how their unit counts stack up.

- McDonald’s ($38.5B): 13,914

- Starbucks ($19.7B): 14,825

- Subway ($10.41B): 24,798

- Taco Bell ($10.3B): 6,588

- Chick-fil-A ($10B): 2,400

And that’s being closed on Sundays.

Also, Chick-fil-A’s average-unit volume in 2018 was $4.166 million. No other fast-food chain in the QSR 50 eclipsed $3 million. Raising Cane’s was second at $2.96 million, but the brand had just 400 stores at 2018’s end—a full 2,000 fewer than Chick-fil-A.

Popeyes’ vitals last year look as follows:

- U.S. systemwide sales (in millions): $3,325.00

- AUV: $1.415M

- Units: 2,368 (2,327 franchised).

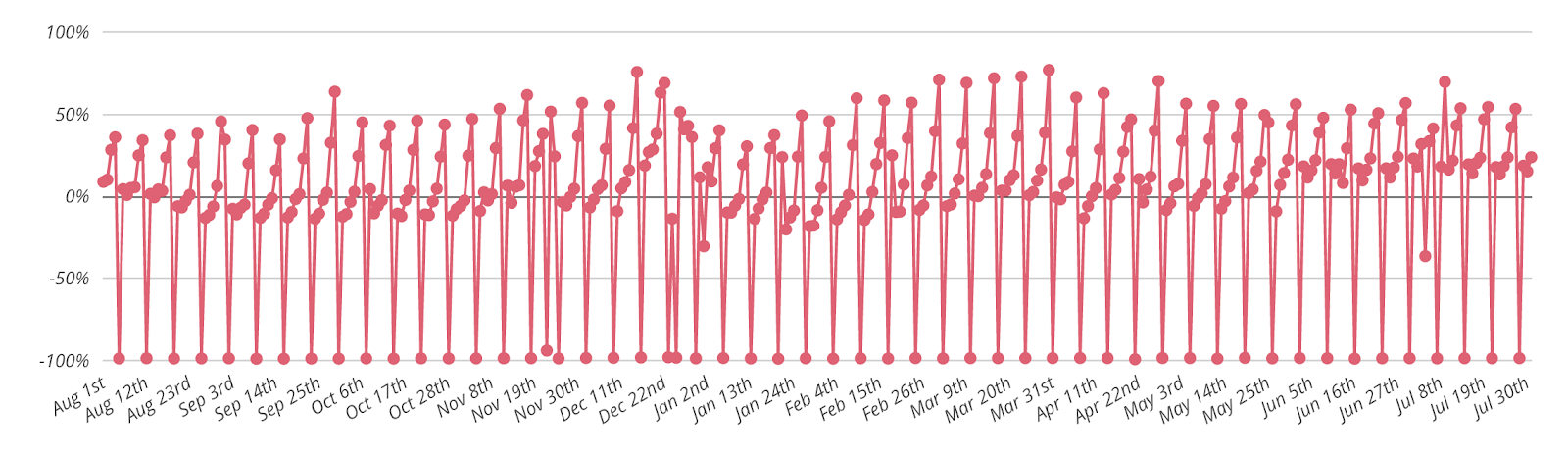

Placer.ai took the same 12-month view of Chick-fil-A with its data. The brand witnessed a traffic pattern comparable to Popeyes, with August results dipping a bit before rising in the winter and spring.

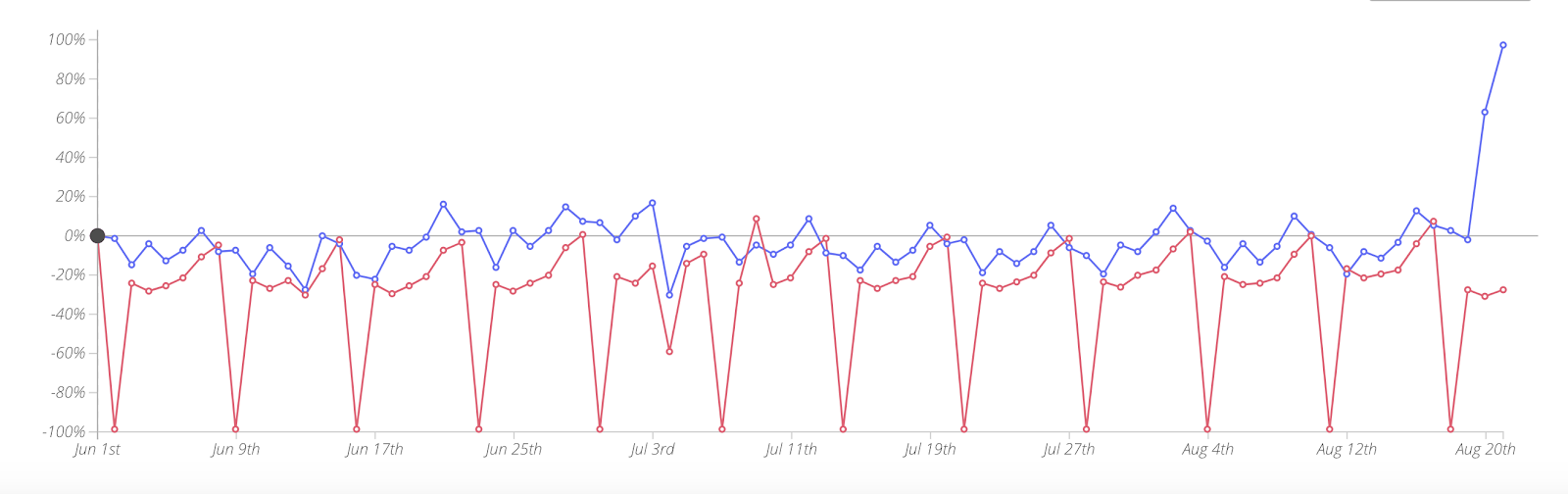

This provides critical context, Placer.ai says. Not only did Popeyes see a spike during a period when a dip might be expected for its own stores—the chain drove a massive increase in visits when even the strongest of the category competitors felt the slowdown. The graph below compares both brands to their respective baselines for the periods. While Chick-fil-A has far more visitors in absolute numbers, Popeyes, without question, saw huge value bounce off the campaign.

And perhaps we’ll find this out down the road, but it will be interesting to see how much Chick-fil-A boosted from the buzz. The answer is probably some. Just not nearly to the extent Popeyes enjoyed, at least compared to its typical traffic trends.

Could we see more of this? Why not. The chicken wars might just be getting started.

Placer.ai extended the analyzed period from June 1, 2018 through August 21, 2019. Two days hiked 88.7 and 128.9 percent above the baseline for the period. “These are insanely high numbers, but there are opportunities for both brands to extend this value far beyond the summer of 2019,” the company said.

The launch has the potential to help Popeyes close a gap between its boneless and bone-in offerings as well, if it can iron out supply. Earlier in the spring, the brand said boneless mixed just 20 percent overall.

Naturally, though, the attention is good news for Popeyes, which has just started to pick up momentum under the Restaurant Brands International umbrella. RBI purchased the brand for $1.8 billion on March 27, 2017.

Popeyes was a consistent performer and enjoyed steady growth heading into the deal. It opened 216 restaurants the year before RBI jumped in, comprised of 118 domestic and 98 international restaurants. That was on par with the previous year’s 219 total openings. Net, Popeyes opened 158 in 2016 compared to 166 in the prior year.

Popeyes’ same-store sales climbed 3 percent in the second quarter of fiscal 2019, year-over-year, including 2.9 percent in the U.S. But comps are slightly negative overall since purchase as the brand integrates into RBI’s system. It ended Q2 with 3,156 global units (2,379 domestic) thanks to net restaurant growth of 6.1 percent. Popeyes also inked a deal to bring 1,500 restaurants to China with TFI TAB Food Investments, the same company that’s built Burger King to 1,000-plus locations in the massive market.