At the apex of lockdowns, fast casuals felt the sting of their own differentiation. The category’s incubation in the 1990s into mid-2010s was largely a real estate deviation. Brands sought in-line, leased real estate in an effort to improve ROI that, at least in quick service, had historically favored fast-food giants. While a less traditional model, it proved fertile. And in rapid response, fast-casual brands of every ilk and category dove in as consumer demand supported it.

There was visible whitespace for high-quality and convenient food served in a setting that catered to a coming generation. Localized designs and on-trend, focused menus. A middle ground between quick service and casual dining. Within a month of Steve Ells turning an $85,000 loan from his father into Chipotle, the assembly line concept was selling 1,000 burritos per day out of its original Denver location.

The Great Recession lowered barriers to entry and triggered the flood, with fast casual growing 10–11 percent for five straight years starting in 2010, according to industry consultant Pentallect Inc. Today, it accounts for roughly 18 percent of revenue driven by the entire limited-service category.

However, one byproduct was the absence of the drive-thru, a channel synonymous with fast food and avoided like the dentist by fast casuals.

And it’s where the pandemic performance gap formed. At peak (the quarter ending June 2020), fast casual visits fell 23 percent, year-over-year, according to The NPD Group. Yet by year-to-date August 2021, they rose 8 percent and traffic was flat on a two-year basis.

What changed? Simply, fast casuals found a way to get their food to guests again. The demand never dissipated—access did. Fast casual off-premises orders in the year ending August 2021 climbed 30 percent over the previous year. Off-premises was about half of the category’s traffic pre-COVID. Now, it represented more than 80 percent.

The end result has galvanized optimism throughout the sector. Tech innovations and fresh asset strategies (drive-thrus and pickup windows are enjoying a renaissance) are helping fast-casual brands threaten share from much larger players once again.

Brett Schulman, co-founder and CEO of CAVA, says the fast-growing Mediterranean brand is “significantly ahead” of where it was in 2019. Mostly, this is a product of pre-pandemic investments set into motion by quarantine conditions. How “COVID served as an accelerant to a lot of the trends that were building underneath the surface,” he says.

READ MORE: Looking for the next big thing in fast casual? Check out this year’s 40/40 List.

When dining rooms closed, CAVA leaned on tech strategies well before it expected to. Its engineering team unveiled marketplace-aided delivery alongside curbside. The pandemic introduced guests to access points glossed over before.

And the spin is a now-familiar story among fast casuals: “We’ve only seen that carry over,” Schulman says. “As our guests return to in-restaurant dining visits, they’ve gained the increased awareness of being able to get their favorite CAVA meal how they want it, when they want it, where they want it.”

Before coronavirus, digital orders represented 20 percent of CAVA’s transactions. It surged to 80 percent amid COVID and moderated at 45 percent. “From a dollar basis, however,” Schulman says, “the sales have stayed sticky. It’s just the in-store has come back so strong.”

Shake Shack CFO Katie Fogertey says the burger brand, like CAVA, plotted major digital moves before a global pandemic sped up the stakes.

Shake Shack launched a mobile app in 2017. Yet here’s an anecdote illustrating COVID’s disruptive nature: Despite having web and app ordering, Shake Shack’s digital business could best be described as “nascent” in 2019. More than 85 percent of sales came from guests walking into restaurants and ordering at the cashier. Echoing Schulman’s point: “However, these earlier investments in app and web allowed us to leverage digital to quickly navigate and scale this business,” Fogertey says. By the second quarter of 2020, Shake Shack’s digital sales soared from 15 percent just a few months prior to 75 percent of total sales, and grew more than threefold, year-over-year.

“Many of the fast pivots in the early days of the pandemic soon became permanent functions, including implementing multi-channel delivery, enhancing digital pre-ordering, and expanding our fulfillment capabilities,” she says.

Similar trends unfurled across Focus Brands’ portfolio (Moe’s Southwest Grill, McAlister’s Deli, Cinnabon, Auntie Anne’s, Carvel, Jamba, Schlotsky’s), says Claiborne Irby, the company’s SVP of customer engagement and strategy. All of that traffic outside the four walls enabled Focus to measure business more effectively, and understand which customers engage in which channels.

“We’ve made the pivot, but now we’re in a place where we’re sitting on a treasure trove of data,” Irby says. “And we need to make sure that we’re driving our brands forward, that we’re putting that to use, that we’re using that data to make smart decisions to drive our brand’s performance and that customer engagement.”

The value and race for guest data can’t be understated at this turn in the COVID comeback. Take Panera Bread. Today, more than 50 percent of the chain’s orders are processed in some sort of digital fashion that captures data (app, online, kiosk, drive-thru, loyalty at the register).

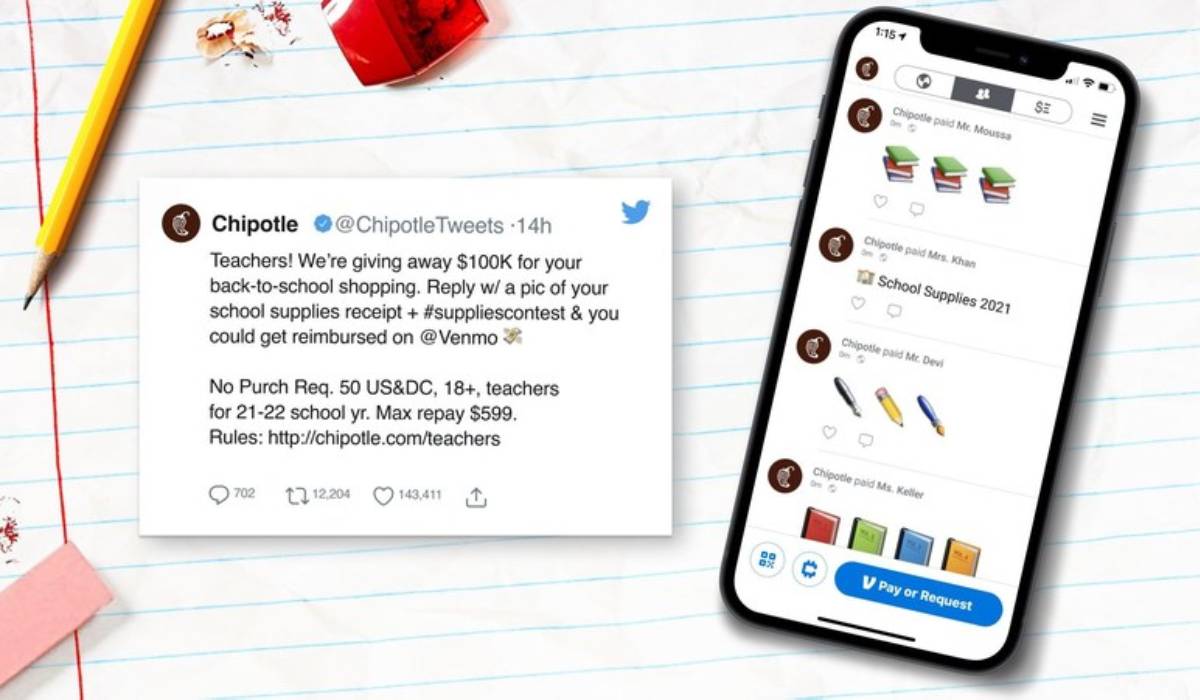

Irby says loyalty will play a lead role in 2020 at Focus. It will be hard-pressed to find a fast casual where that’s not the case. Before COVID, Chipotle had fewer than 10 million rewards members. Come December 2021, there were 24.5 million.

“It’s not just transactional,” CAVA CEO Brett Schulman says. “And you’re not just tasting our brand through the food you’re eating but you’re feeling our brand through the digital hospitality you’re getting in your digital experience

Loyalty helped fast casuals gain on aggregator platforms as well as top competitors, and to keep customers in the funnel through tactics other than deep discounting or coupons—avenues larger quick-serves will almost always win on. Chipotle today is using methods like predictive modeling to trigger purchasing journeys.

“We want to make sure customers are getting the best experience possible using the information we’re seeing from people in loyalty, and outside of loyalty, to help our brands remain relevant and push our brand’s commercial performance on driving that demand generation,” Irby says.

Accessibility and customization are consumer expectations now, he adds. So is driving a one-to-one relationship. McAlister’s, for instance, added tableside ordering to layer in a digital format inside of physical stores. Customers sit down, skip the line, order and customize how they want via the app, yet get the meal-to-the-table service McAlister’s is known for.

“I think that’s going to be one of the most important things for brands in the coming year, is maintaining that customer experience, owning that customer experience across the physical and digital,” Irby says

“I think there’s never been a more exciting time for the industry,” he adds, “because technology has never been more accessible to restaurants. Even a single store can get a web and an app and experiment with ghost kitchens through third-party delivery. But it’s never been harder to achieve scale. It’s never been harder to own your customer’s experience and turn that data into a competitive advantage.”

Thirty-eight-unit Piada Italian Street Food started its push into digital in 2017, as Shake Shack did. Matthew Harding, senior vice president of culinary and menu innovation at the brand, says Piada rolled out online ordering and bought a generic app. The coming year, Piada brought that technology in-house and started to implement functionality to “punch over our weight.” The company’s apps launched November of last year and have seen about 10–15 percent growth per week. “When we realized that was going to be the savior, we really rushed in,” he says.

In its infancy, fast casual’s super power was the ability to blend experience with convenience at a price point consumers hadn’t seen before. Digital boom or not, CAVA’s Schulman says, the demise of in-restaurant dining was exaggerated. At Piada, in-store traffic gained 15 percent over the summer. Another case point—CAVA saw dinner business grow by 10 percent over pre-virus.

Here, fast casual has a chance to dig in against fast food, akin to the 90s. The idea fast casual “offers the best of both worlds” and can also grab share from full-serves by competing on quality.

Torchy’s Tacos founder Mike Rypka says human beings are social by nature, and the demand to gather didn’t evaporate when the option did.

“No one really loved being locked down in their house the last 18 months,” he says. “I think there’s still a big need for that.”

Torchy’s will continue to commit to an experience that courts a social, inviting environment far removed from the “food-as-fuel” chains of past quick-service lure, Rypka adds. This means full-service bars and ambiance, and branding felt across the 95-unit fleet.

“Also respecting and knowing that you’re probably leaving money on the table if you’re not investing and working on your digital to-go experience,” he says. “You’ve got to tackle both, and for us that’s very important.”

Thanks to COVID, guests now have a drive-thru menu in their hands, Schulman says, which also blurs the lines in fast casual’s favor. Piada’s Harding refers to this as the ability to “meet guests at the screen.” They can order ahead and go to curbside, or run to a pickup shelf. “You have the [quick-service] convenience with the quality of a fast-casual experience,” Schulman says. “But you can also have the ambiance or the quality of food that you can get at a casual-dining [brand] without the time or price commitment.”

Rypka says Torchy’s is looking at pay-at-the-table, increased curbside, and just offering more channels to communicate and reach out to guests. “Definitely, I think that’s the wave of the future,” he says.

Evolution in store (literally)

The pandemic created a far more flexible and dynamic fast casual world. CAVA, for instance, opened a store in November in Castle Rock, Colorado, with a pickup window and dining room. It has a Bryant Park, New York, unit without any seats. Guests order down the line, but everything is packed and sent out the door. There are also some CAVAs with upward of 80 seats. Coming in February 2022, it’s flexing again with a Sandy Springs, Georgia, digital pickup kitchen—a first for the brand. It’s a storefront for digital-order pickup, delivery, and catering production to support the company’s recent push into the latter.

“This new, multi-channel world that we’ve evolved allows us to think about our real estate differently and adjust our real estate to the needs of our guest in that given neighborhood or trade area,” Schulman says.

CAVA has the added benefit of its $300 million acquisition of Zoës Kitchen from 2018. The brand planned to convert a total of 55 in 2021 with another 60-plus on deck for 2022. It’s given CAVA an outlet to expand without typical challenges of sourcing real estate, like negotiating leases or developing a site from scratch. It went from having zero Atlanta stores in May to 14 by November. Dallas began 2021 with two and now has 14 as well.

This, too, fits into a broader fast-casual reaction out of COVID. Today, 80 percent of CAVA restaurants, notwithstanding the Zoës acquisition, are suburban. Nearly all of the Zoës brought into CAVA’s fold are.

The days of fast casuals tying their fortunes to city markets are gone. And with that, the opportunity to open more drive-thrus and versatile formats knocked. Off-premises strengths and how COVID crossed the digital adoption gap, gave fast casuals the ability to rely less on foot traffic to build brand recognition and awareness.

It’s an especially vivid reality at Shake Shack, which is also placing a larger focus on suburban growth (more than half of Shake Shack’s planned corporate openings in 2022 are going to come in suburban markets). Fogertey says the brand’s digital business was scaling too fast to settle on just having functionally to order digitally. That led to the creation of “Shack Track,” a digital pre-ordering and fulfillment experience that includes pickup shelves, curbside, pickup windows, multi-carrier delivery, and, more recently, drive-thru. Shake Shack opened its first in early December in Maple Grove, Minnesota, and plans to have 10 by year’s end.

The venue features a digital menuboard, two-lane ordering system, and separate pickup window. Additionally, there’s a split-kitchen design with a separate kitchen dedicated solely to drive-thru business.

“The need to enhance and alter the physical restaurant to meet the needs of digital is so important to Shake Shack that today, nearly all new restaurants we open have some aspect of Shack Track,” Fogertey says.

It’s a significant point as Shake Shack gears up for its biggest corporate growth year on record in 2022, taking aim at 45–50 new stores. “We are a young company with just over 200 company-owned restaurants in the U.S. today,” Fogertey says. “However, we know our guests expect our digital experience to be at parity or even better than other restaurant brands with more units and more resources. We have had to be and will continue to be strategic with our investments, but most importantly, we will continue to invest in digital initiatives to help welcome more guests into our omnichannel.”

The funnel grows

Between March 2020 and November 2021, Shake Shack welcomed more than 3.2 million total purchases on its company-owned app and web channels. In just Q3 2021, this base grew 14 percent, quarter-over-quarter, and more than doubled prior-year levels.

The brand retained about 80 percent of digital sales from pandemic peak (June 2020) and digital mixed 42 percent of total business.

CAVA’s digital base boomed as well, up twofold over the past two years. The brand updated its app to more closely mirror CAVA’s in-restaurant, down-the-line experience as it began to think through another fast-casual strength—hospitality without the need of a server. “It’s not just transactional,” Schulman says. “And you’re not just tasting our brand through the food you’re eating but you’re feeling our brand through the digital hospitality you’re getting in your digital experience. … Clearly, our guests are enjoying interacting with us in both ways.”

Shake Shack knows this ethos all too well. New York restaurateur Danny Meyer started the brand as a small, local installation to help support the refurbishment of Madison Square Park. The first Shake Shack trialed as a hot dog cart in 2003 and evolved to a permanent kiosk across from the Flatiron Building as a riff on the American hamburger stands of the 1950s and 60s. It’s never looked, or felt, like your parent’s fast-food chain.

So how can you push experience despite the impersonal nature of off-premises business? “We are always going to be focused on gathering communities, enriching our neighborhoods, launching great products, and driving our brand in new and innovative ways,” Fogertey says. “Our digital channels allow us to do this and help convey what makes Shake Shack special and how we stand apart from traditional fast food. We at Shake Shack are known for our hospitality, and we have pushed beyond our physical walls over the past year and a half to connect with our guests in ways we haven’t had the opportunity to do before.”

In urban markets, Shake Shack installed walk-up windows and dedicated entrances with pickup shelves for to-go and delivery orders. Kiosks, of which the brand continues to invest in, were designed to help guests navigate the menu and premium add-ons more easily than traditional menuboards, Fogertey says.

“In the Shacks where we offer a kiosk order mode, 75 percent of our sales come through that channel as well as our digital channels,” she explains. “Kiosks also help our team members be more efficient, and over the long term, our investments will allow us to expand our digital and omnichannel ecosystem.”

Drive-thru emerges

Cousins Subs is another brand rethinking physical infrastructure to address demand. About 40 percent of the 100-unit chain’s system includes drive-thrus today, and it’s looking for opportunities to add more. Stores perform 20–30 percent better and, as of November, Cousins had six company units in development, and all included a window. Brand president Jason Westhoff says lease rates on drive-thru facilities climbed “anywhere between $5–$10 a square foot” as landlords and developers rushed to cash in.

It’s just one element of a blurring movement, though. Westhoff believes current trends will continue at least through the year, and the pandemic won’t go out with a bang.

“I don’t know if we’ve reset the guest expectations or if the guest is resetting expectations for us,” he says.

“My belief is that a lot of people found that during the pandemic they weren’t good cooks and they liked the experience of not having to spend time preparing meals, and fast casual was filling the void at home because the food was either perceived to be a better quality or there were more choices,” Westhoff adds.

At Focus, about half of customers are using drive-thru and pickup and the company expects that to hold going forward, if not increase. Either way, Irby says, Focus is readying for a landscape where consumers demand the best of both, and get a branded experience across all of it. More than a third of its customers get delivery at least once a week. “That’s opening up new occasions, both for us to serve existing customers and to gain new customers,” Irby says.

Piada has pickup windows in about 25 percent of its locations. As Chipotle continues to prove with its “Chipotlane,” fast casuals can now tack on drive-thru business without adding high-cost items like menuboards. “It’s really a frictionless thing,” Harding says. “You’ve made all of your decisions, you just wait until the allotted time, drive up, pick up your food. It’s pre-paid. You’re eliminating a lot of the pain points. I don’t know about you, but when I go up to a drive-thru and I’ve got five people in the car, my family, I get anxious because I know what I want, but they won’t think about what they want until they’re asked.”

Labor and culinary offer a leg up

Regardless of where the consumer takes fast casual, the labor challenge will linger inside restaurants. Wages historically don’t retreat after they rise. Fast casuals are in a unique spot here as well due to the fact their core guest is often younger and more interested in aligning with a brand they believe in than some larger corporations.

It’s why Cousins Subs’ Westhoff sees retention, not recruitment as the labor battleground of 2022 for the category.

The chain upped wages and took a deeper look at benefits, like daily pay and free meals. It made it easier to apply for jobs and invested in retention bonuses. Managers conduct quarterly check-ins with hourly employees and teams hold daily huddles. “What we try to do is focus on retention instead of restaffing, and the best way we can retain is to create a good culture,” he says. “And good culture happens in a thousand different ways, but the biggest way is to create touchpoints for every single person in the organization down to the newest hourly employee. … I think anything we’re doing to make the brand better today is going to last.”

Schulman says COVID awakened people to their surroundings. “Who am I working for? Why am I doing this work? What is the greater purpose behind it?” he says. “I think it’s imperative for any brand to be able to clearly communicate that. … . Having a positive impact on the communities that we serve—that’s going to motivate people to come to work for us, and to stay working for us.”

Wages are up more than 12 percent at Piada. But it’s a cost the brand would rather incur than cede ground on service and lose some of what makes fast casual special. “The thing you have to remember is if you don’t have our team members giving great hospitality, you don’t have crap,” Harding says. “… We’ve got to take care of that initial thing, which is getting our team and getting our guests happy. Right now, those are the two things that should be tattooed on the inside of your eyelids.”

And just as fast casuals continue to lead with service, décor and experience, menu diversity is going to offer these brands a leg up in 2022, Harding says. That move to comfort food when the crisis spiked? “You’ve got palate fatigue,” he says. “In the initial phase of the pandemic I’d talk to friends and [pizza] was all they had two, three times a week, and then they got tired of it,” he says. “They began to kind of explore a little bit, and they found brands and they found restaurants that offered a little bit of differentiation.” Piada ran elevated LTOs over the summer, and “Cannoli Chips” in the fall.

“Those types of things have helped to accentuate the differentiation [for fast casual], the focus on the food, the freshness cues for the guest,” Harding adds. “And guests still want those things.”