Airports across the U.S. are adding a more local feel to their concourses in an attempt to offer travelers a better sense of what that city has to offer.

National fast food brands should take note. As airports strive for more of a local feel, limited-service companies that are pushing nontraditional expansion and putting airport concourses in their crosshairs could be squeezed out of those locations.

While national restaurant brands still dominate airport terminals, the last 10 years have seen a rise in the percentage of local-dining options as airports have sought to cultivate a “sense of place” by favoring vendors based in the airport’s host city.

Bill Casey, vice president at HMSHost, a master concessionaire at about 70 domestic airports, says local brands today account for as much as 40 percent of dining options at the average airport. While he expects the ratio to decrease slightly in the coming years, the trend of airports leveraging local brands is here to stay, he says.

“There will always be a mix,” Casey says.

That wasn’t always the case, he says. Throughout the ’80s, airports offered travelers national dining options almost exclusively. The shift to a mixture of national and local brands started in the mid-’90s and continued throughout the following decade, with airports around the country emphasizing local brands to varying degrees.

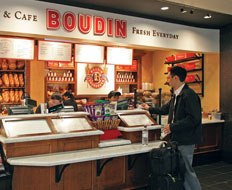

One of the airports at the forefront of the local-dining trend was San Francisco International Airport, where local brands now comprise 85 percent of the foodservice offerings.

San Francisco International used to use HMSHost as its master concessionaire, but in 2005, concurrent with a large renovation of its domestic terminal, the airport decided to contract with individual vendors, most of them local.

Conventional wisdom would suggest that national brands tend to drive higher sales than local brands in a high-volume environment like an airport, especially because many patrons are from out of town. But after San Francisco International switched to a food program stocked primarily with local brands, sales went up by 55 percent, says Cheryl Nashir, associate deputy airport director. Today the airport is No. 2 in the country in terms of food and beverage spending per customer, at $6.85.

The rationale behind the change in strategy, Nashir says, was that the publicly owned airport should support its own community.

“It is really important for us to support our local businesses,” she says. “We are part of the San Francisco community, and we like, to the greatest extent possible, to do business with San Francisco businesses.”

Furthermore, Nashir says, showcasing San Francisco–based restaurants, including those with only one other location, gave the airport an “authenticity” that national brands could not duplicate because of their ubiquity in cities around the country.

Although Nashir draws a comparison between airport dining and commercial mall food courts, airports aren’t destinations but rather venues through which travelers hurry on their way to or from an airplane. She says this doesn’t detract from customers’ desire to have quality, authentic locations where they can dine.

“We think the fact that travelers spent more shows that they care,” she says. “They reached in their pockets and spent more money. We think they are willing to pay for quality and that they are more satisfied.”

With faith in the power of local flavors driving higher sales, San Francisco International recently launched the Napa Farms Market. The market offers locally sourced gourmet food items and lets plane-bound travelers assemble their own “picnic basket” before boarding.

To be sure, San Francisco International represents one end of the spectrum when it comes to this trend. But with airports across the country adopting this strategy, national companies are offering to roll out their own local versions of their brands in order to secure airport locations.

Brian Boycan, director of strategic development for Auntie Anne’s, a pretzel concept with 40 airport locations, says one way the chain adheres to the trend is by offering pretzels with popular local flavors. For example, jalapeño pretzels are served in Southwest markets. Still, Boycan says meeting the demand of local travelers can be difficult for a nonlocal brand.

“A national brand has limits as to how it can comply with the request for local flavor,” he says. “So what we do is we focus on our common roots.”

In a recent proposal submitted to Dallas Love Field Airport, Auntie Anne’s emphasized the fact that it has 26 on-the-street locations in the area. The Pennsylvania-based company stressed that this made it a part of the fabric of the Dallas business community.

“We really try to bring to the proposal a partner who is a local operator,” Boycan says. “I think that is important.”

Another way national brands can fit with an airports’ sense of place is through décor, says Chris Cheek, vice president of franchise development for Bruegger’s, a bagel concept with about 20 domestic airport locations.

“In the Southwest, for example, we may use adobe-stacked stone as part of the [façade] of our units,” says Cheek, who calls localization “one of the most significant trends in the airport industry.”

Those national brands that don’t want to compete with local concepts in airports or that are unwilling to adapt their concepts to local tastes may want to consider the other two trends in airports, Casey says: healthy foods and upscale, fast-casual locations.

The worst thing restaurants could do is not try to land in an airport at all, he says. While securing an airport location may be tough, restaurants “do twice the business in airports that they do on the street,” Casey says.