In 1970, Dave Thomas introduced what’s generally labeled the first modern drive-thru, a feature the Wendy’s luminary coined the “Pick-Up Window.” It was so revolutionary guests needed instructions on how to talk through the speaker to place an order.

In some ways, the COVID-19 era feels the paradox of this 52-year-old page in fast-food history. Consumers today, according to the survey portion of the 2022 QSR® Drive-Thru Report, are more satisfied with their drive-thru experience than at the peak of the pandemic. It’s why brands, from Wendy’s to Chipotle to Applebee’s, haven’t dialed back in light of cafes reopening across America. If anything, the COVID stabilizer has become the industry’s most innovative arena. And customer behavior was hardly disrupted the way it was five-plus decades ago. Upgrades such as better signage, sanitation, and, of course, technology, were ticks guests had been waiting for.

Deepak Ajmani, Wendy’s U.S. chief operations officer, has seen this clearly in recent data. The burger chain adopts an “always on” approach highlighted by its Voice of Customer satisfaction survey, as well as employee and social feedback. Of late, the same line revealed by the QSR® Drive-Thru Report continues to flash. “Insights from the survey responses have revealed an upward trend in satisfaction, indicating that customers are more likely to return to our restaurants,” he says.

This year’s QSR® Drive-Thru Report surveyed more than 1,000 consumers who had visited at least one drive-thru in the previous 30 days. What’s also visible is this rising sentiment owes a good deal to technology.

RELATED:

Download Intouch Insight’s Full Report

Customers Pick Their Favorite Drive-Thru Chains

Taco Bell’s Gravity-Defying Restaurant is the Future of Fast Food

How the Pickup Window has Changed the Drive-Thru Game

The Menuboard Optimization Trilogy

What’s Next for the Fast-Food Drive-Thru Menuboard?

In Search of the Perfect Drive-Thru Restaurant

Perhaps the best way to illustrate it is to go back in time again. The first drive-thru sprung up in 1947 on Route 66 in Springfield, Missouri. The late Red Chaney’s Red’s Giant Hamburg claims the title, although loose-meat sandwich chain Maid-Rite says the same (a year later in 1948). The original In-N-Out Burger—1948 in Los Angeles—is likely the longest-running given Red’s closed in 1984, while Jack in the Box, come 1951, boasts the definition of the first drive-thru-focused chain to open as such, which it did at a time when car culture lit up the landscape.

But semantics aside, the concept was straightforward at creation—provide a counter to the carhop service consumers were familiar with. And it was billed as more convenient for guests and restaurants alike. Guests responded.

So it bears asking what are diners giving restaurants credit for at the drive-thru today, and why is that shooting satisfaction higher? When asked what the top two reasons they choose to order using the drive-thru were, per this year’s study, guests picked “Convenience” and “Speed of Service.” Similar to last year’s edition, it’s become crystal those factors aren’t tied at the hip any longer. In fact, one is holding fort while the other ebbs. Seventy-eight percent of customers picked convenience as their No. 1 drive-thru draw. That figure was 79 percent last year and 75 percent in 2020. Speed of service, meanwhile, clocked in at 42 percent, a full 9 percentage points down, year-over-year (it was 45 percent in 2020). For vital factors driving future drive-thru visits—what would inspire a repeat trip—more than half (58 percent) indicated order accuracy was most important. It was more than twice the second metric, speed of service, at 23 percent.

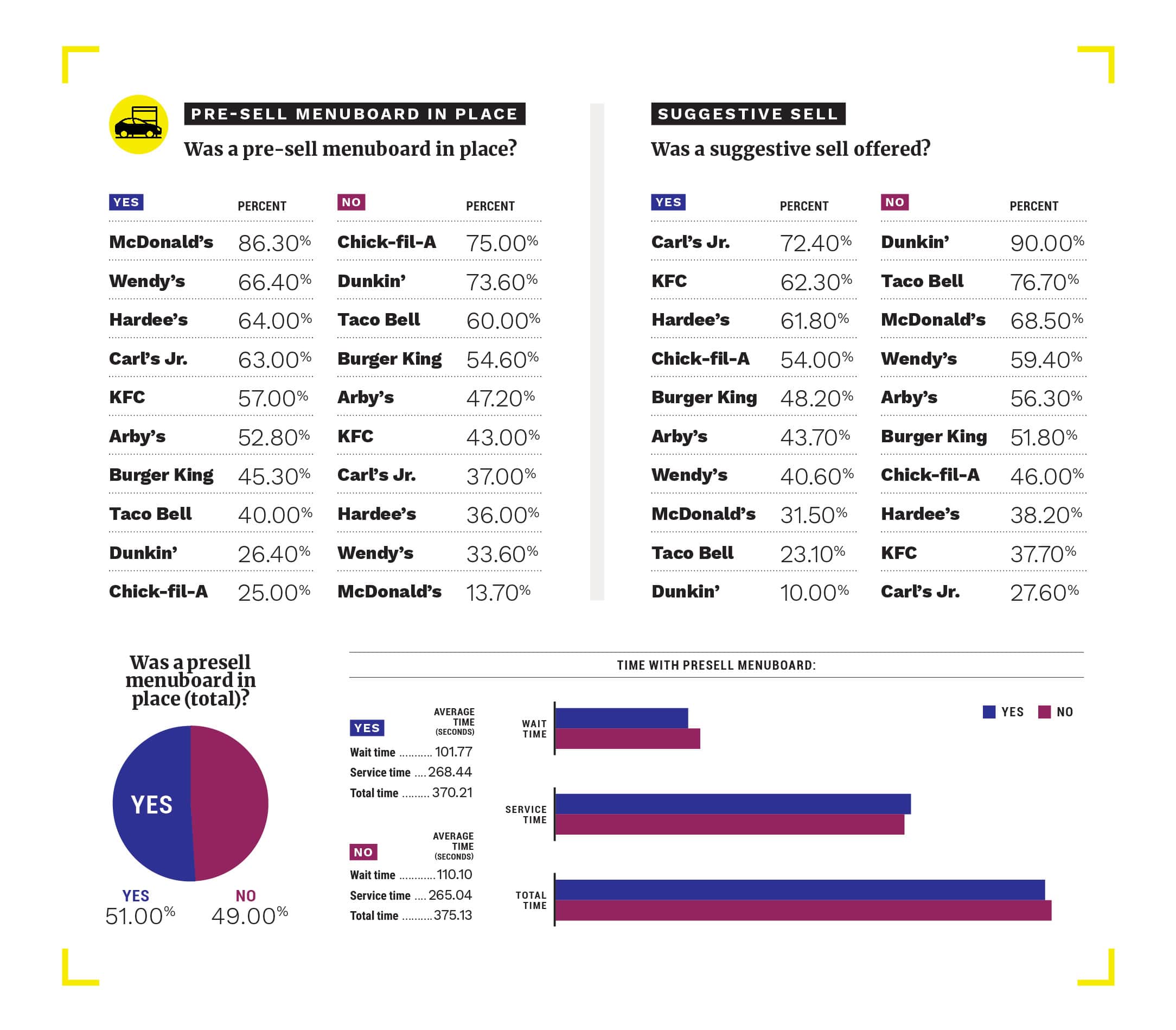

A menuboard placed ahead of the ordering speaker (18 percent), order confirmation screens (18 percent), and the ability to pay with mobile phone or app (11 percent) rounded out the top 5.

This isn’t to say speed of service at the drive-thru has become obsolete through the COVID window. Customers in the survey said they’d be willing to spend 13 minutes when ordering through a drive-thru (same as last year and a minute higher than 2020). They noted they typically wait 10 minutes and think 8 is ideal.

Respondents considered it reasonable and fair to spend just under 6 minutes prior to ordering; 4.95 minutes between placing order and picking up; 4.72 parked in a separate waiting area at pickup when order was not ready; and 3.38 placing their order.

Speed now is simply a more involved transaction that restaurants can influence from fresh angles.

Despite reopening dining rooms, Ajmani says drive-thru has remained Wendy’s customers’ preferred way of interacting with the brand, and it’s due to the fact it addresses three critical elements of the quick-service experience: accuracy, convenience, and speed (as the survey data reflects).

In the past year, Wendy’s took a four-pronged approach to elevating these bars. It expanded convenience ordering options, including through the Wendy’s app, kiosks, and pickup spots and grab-and-go shelves. “These options allow customers to interact with us using the platform of their choice,” he says.

Alongside, Wendy’s opened dining rooms for guests who prefer it, and continues to encourage customers to “go digital” by using mobile carryout via Wendy’s app. Consumers order ahead and schedule a pickup time. When they arrive, they park in dedicated mobile pickup spots, come inside, grab their order, and leave without getting in the drive-thru line.

Lastly, Wendy’s is testing new processes at the drive-thru itself, like separate windows and pickup points for delivery drivers. The latter shifted some of Wendy’s largest orders out of the pickup window lane.

But this is where the puck has been sent forward for restaurants. “Omnichannel” was a term on the minds of every operator when COVID hit. Once drive-thru capacity stuffed, restaurants rushed to open channels of trade to meet guests where they were.

The idea today that a restaurant has a mobile app or offers website ordering is far from a differentiator. If guests can’t access the brand through the means they want, they head elsewhere. You could even argue the experience must mirror ecommerce habits in general. Friction in the ordering process has become the throughput divider of a changing generation.

How does this affect drive-thru? As we’ll explore, it’s a puzzle of integration and connectivity. Frequency is here to stay, and so are the newfound ways restaurant customers want to order. COVID essentially put a drive-thru screen in the hands of nearly every consumer in America. It’s a reality that both raises the stakes and opens the potential.

Wendy’s, for one, is exploring what it says is an industry first, where customers can use voice AI tech to place orders with Coca-Cola Freestyle machines via speech. Their choice is then dispensed in the dining room while crewmembers focus on preparing the rest of their order.

The brand also rolled the availability of hand-held point-of-sale devices systemwide. Like Chick-fil-A and In-N-Out, employees have the ability to roam the drive-thru lane and take orders directly at customers’ cars during peak periods.

In the back of the house, at many locations, Wendy’s implemented new solutions like Pickup Window Timer Leaderboards, which rank the restaurants within a district or area on their service time achievements; and optimized bagging procedures where new kitchen video screens offer a clear and reflective breakdown of drive-thru, mobile, and register orders to help employees accurately fulfill requests.

And it’s coming to life from the ground up. Wendy’s unveiled a new traditional build in mid-August that’s going to be its future-forward design standard, called Global Next Gen. There’s a dedicated drive-thru window to help delivery partners pick up orders and an optimized kitchen layout orientation designed to boost efficiency through touchpoints. Dedicated mobile order and delivery parking, and mobile order pickup shelving, finish the model.

“We still focus on car counts and speed of service, but accuracy and taste of food as well as overall customer satisfaction and likelihood to return are also crucial indicators,” Ajmani says.

Let’s talk more about speed

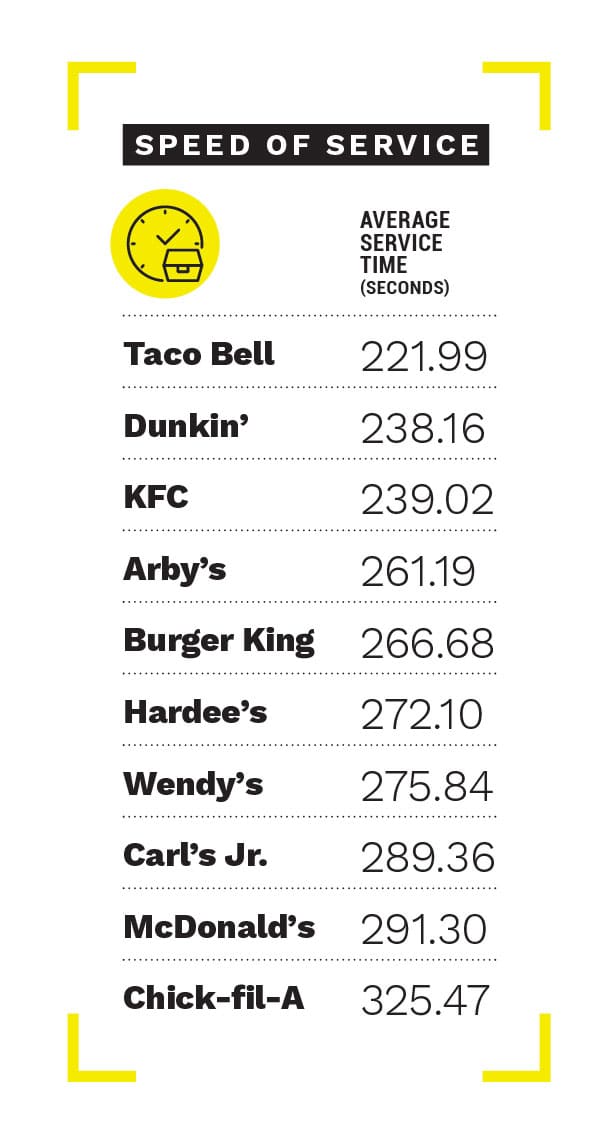

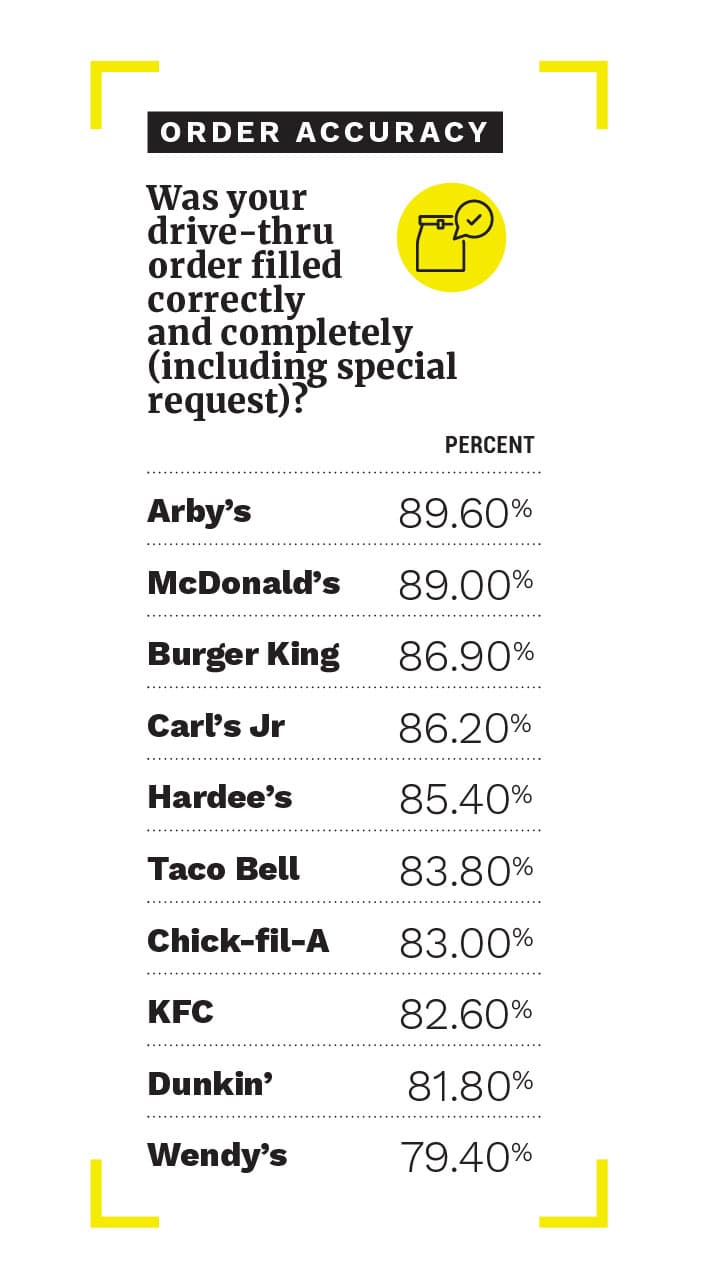

Chick-fil-A’s performance in the QSR® Drive-Thru Report has become a yearly practice of juxtaposition, and one that bespeaks broader trends. The brand lagged the field in average service time at 325.47 seconds, according to Intouch Insight’s Annual Drive-Thru Study, which serves as the data portion of this year’s report, based on store audits (see bottom of story). Taco Bell paced the pack at 221.99 seconds. Both have become familiar results. But calling Chick-fil-A the country’s “slowest” drive-thru falls well short on context, as customer sentiment backs. The chain was given a 93 percent for speed of service satisfaction, per the survey, which trailed only Arby’s (96 percent). So if it is, indeed, “slow,” guests don’t seem to agree.

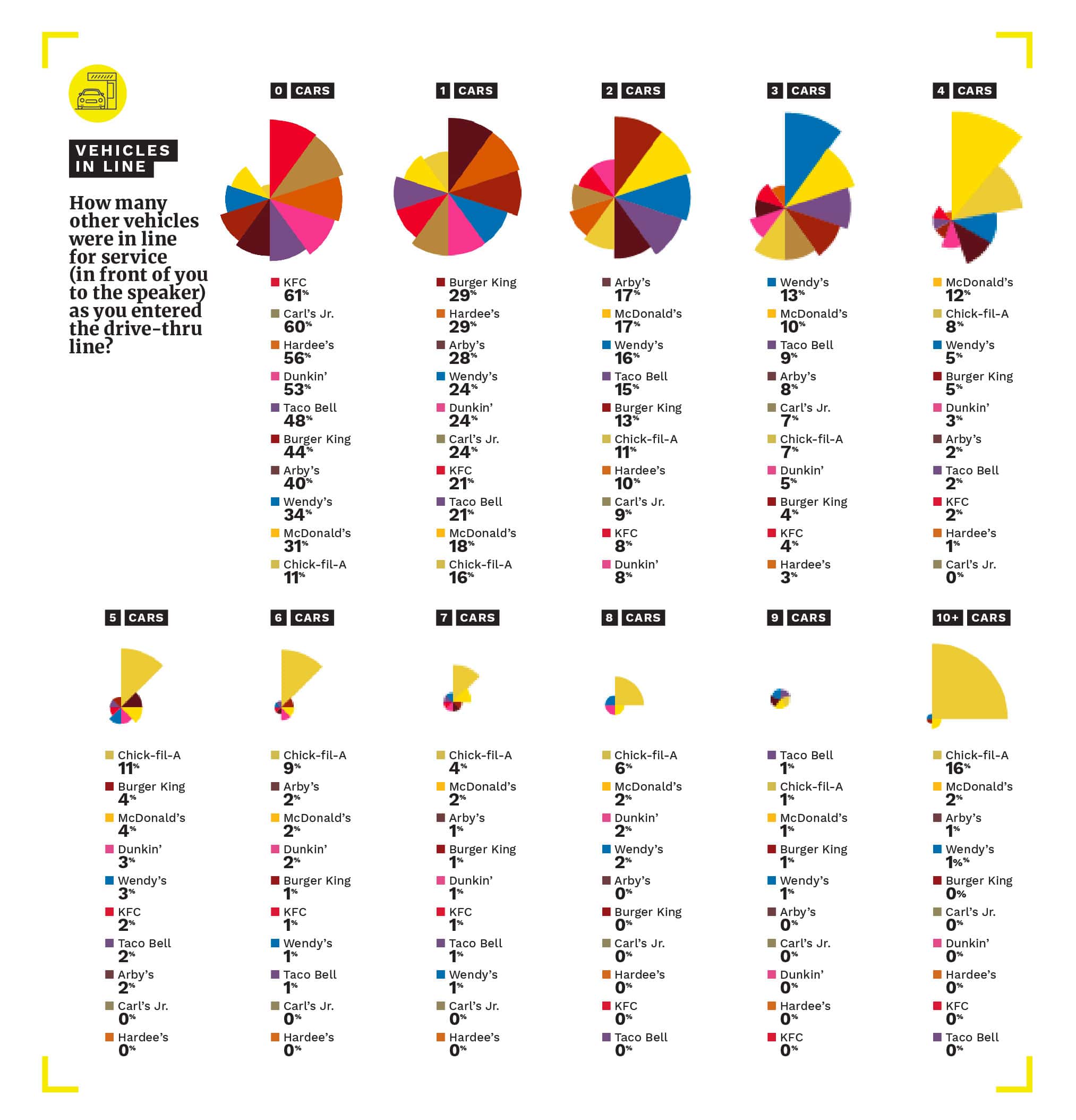

It boils down to a few realities. The first is a stark, undeniable one. As you go down through Intouch Insight’s dive into how many vehicles were in line at drive-thrus, the numbers start to flip. Chick-fil-A begins at the bottom—only 11 percent of the time a driver pulled up were there no cars ahead—and rockets into its own stratosphere at the five-car mark. There, shoppers saw five vehicles lined up nearly 11 percent of the time. The closest brand was McDonald’s and Burger King at 4 percent.

The most telling stat, however, is the 10-plus cars metric. There, Intouch Insight data discovered lines of that length and longer 16 percent of the time at Chick-fil-A. McDonald’s followed at 2 percent, while Arby’s and Wendy’s each notched 1 percent. Everybody else was at zero.

The average cars in line went as follows: Chick-fil-A, 5.45; McDonald’s, 3.13; Wendy’s, 2.67; Arby’s, 2.28; Burger King, 2.19; Taco Bell, 2.17; Dunkin’, 2.11; KFC, 1.8; Hardee’s, 1.64; and Carl’s Jr. 1.63.

The notion is clear-cut: Chick-fil-A’s drive-thrus were “slower” because they were busier. There were more cars for shoppers to get through. And this goes far beyond anecdotes. According to filings, of the chain’s 1,836 U.S. freestanding restaurants outside of malls last year (those open and operated for at least a full calendar year, from a total of 2,023), average annual sales volumes were $8.142 million, with 849 of those, or 46 percent, producing figures at or above. One operator pushed $17.16 million.

For perspective, if you put Outback and Cracker Barrel together, you’d be at $7.92 million.

Another way to look at it is average total time by cars in line. The script changes, reflecting what felt true on the ground—that Chick-fil-A was moving those massive lines in a hurry:

- 1. Chick-fil-A: 107.41 (seconds)

- 2. McDonald’s: 118

- 3. Taco Bell: 127.58

- 4. Arby’s: 139.92

- 5. Dunkin’: 140.21

- 6. Wendy’s: 141.67

- 7. Burger King: 147.43

- 8. KFC: 142.84

- 9. Hardee’s: 180.21

- 10. Carl’s Jr. 193.6

Matt Abercrombie, Chick-fil-A’s senior director of service and hospitality, says the brand has approached drive-thru consistently through COVID—“This idea that we know in the drive-thru the guest wants speed and accuracy, but they don’t want to feel rushed,” he says.

Chick-fil-A was one of the early brands to shutter dining rooms back in March 2020. Its focus went right to bringing hospitality outside. Face-to-face ordering is a model Chick-fil-A has deployed for years, and one that’s started to proliferate industry-wide, as Wendy’s hinted.

“We believe that looking eye-to-eye with the customer allows for a connection that happens at the beginning of the drive-thru,” Abercrombie says.

That’s one part of it—this notion Chick-fil-A can move the line but not in a way where the customer feels less cared for. Think of it like a full-service restaurant conducting table checks instead of seating a guest and disappearing for 30 minutes.

The other element, though, is it’s redefined the static nature of classic drive-thrus. As Abercrombie describes, if you pull into a drive-thru and there’s a car ahead with a family of five, it’s a far different experience to get your order in than wait until they’re finished so you can pull ahead.

Amid COVID, Chick-fil-A refined the approach by fine-tuning what’s basically a check-point system where customers interact with employees at multiple points before pickup. It keeps users engaged and also enables Chick-fil-A to adjust based on individual orders, not just the queue. For instance, alerting one car to pull forward to a waiting spot while sending another to the window. You’ll also see this with order takers walking alongside cars as they move up.

In the QSR® Drive-Thru Report survey, roughly a third (31 percent) of consumers demonstrated a preference to placing orders with an employee in line. What that suggests is some still view using a speaker/pay window as a quicker option. To put it plainly, not everyone is doing it as effectively as Chick-fil-A yet—there’s more to the model than placing employees outside.

At one Central Florida Chick-fil-A, to share an example of the detail required, the location puts numbers on car windows like tables in a dining room. One employee serves as a traffic controller, like you’d see at an airport (39 percent of respondents in the study said merging in a double drive-thru lane gave them stress), and funnels cars from multiple lanes in. The window numbers allow employees—all connected via devices—to know whose order pulls up by the car number and to not only react accordingly, but to offer them personalized service.

There are also some Chick-fil-As where employees are outside the drive-thru window and physically bring the food over. “I think that’s another opportunity to connect with the customer, and so that’s what we wanted to do,” Abercrombie says. “We want to know our customers, we want to connect with them, we want to make sure that they’re not only getting great food, accurate order, but that they feel cared for in the process, personally and connected with.”

And it shows up in data, too.

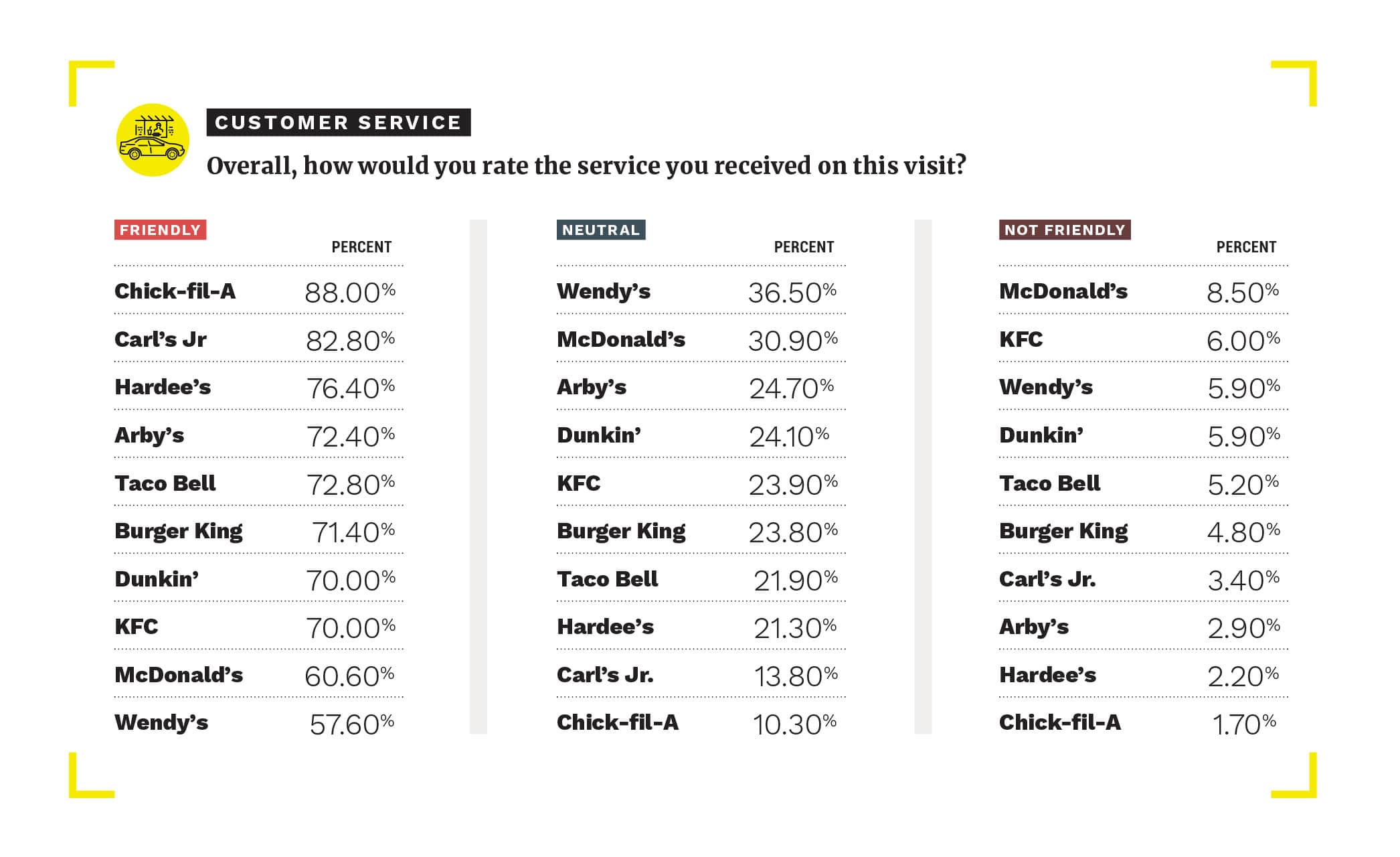

“Although technology and configuration are critical elements to offering a smooth drive-thru experience—nothing trumps the service your employees deliver,” says Laura Livers, senior director of business development at Intouch Insight. “Year after year, the data shows that order accuracy is 15 percent higher when the service is rated as ‘Friendly,’ an increase of 1 percent over last year’s data.”

“And not only does accuracy increase when employees take a friendly approach with customers, but the whole experience is accelerated,” Livers adds. “The average total time with friendly service is almost three and a half minutes faster than with unfriendly service.”

These efforts are rooted in hospitality for Chick-fil-A, but they’re also a reaction to what quick-serves throughout the sector addressed in 2021: overflowing capacity. Turning site pads into transaction centers (think curbside spots) has been one counter.

So have been the lanes themselves. It was a common sight to see makeshift multiple-row setups in 2020. Operators headed to home improvement stores and grabbed a few cones and got to work.

The lasting view, though, is going to take an integrated approach as much as one that simply allows more cars to flow in. Chick-fil-A in June announced it was testing an “express drive-thru lane” in about 60 locations, with further rollout likely. Jonathan Lassiter, a senior integration leader on Chick-fil-A’s service and hospitality team, called it “a game-changer for our busy customers and our team members.”

Logistically, it’s a partially or fully dedicated lane (depending on the site) that enables customers to order ahead and bypass the other line and go right to pickup. Users choose a location on Chick-fil-A’s app, select “Drive-Thru Express,” and place an order. When they arrive, signage points to the express alley, where they use the app to scan a QR code in the dedicated lane before pulling around to receive their order from a Chick-fil-A employee. In tests, the company said the express lane decreased wait times “significantly.” And “most guests” were choosing to use it again on their visit.

In the QSR® Drive-Thru Report survey, about a third (38 percent) of consumers found mobile ordering for drive-thru very appealing.

Like Wendy’s, Abercrombie says Chick-fil-A’s busy drive-thrus didn’t vanish when dine-in mandates did. There have been plenty of stories of the brand’s lines causing traffic jams and prompting meetings. In Pennsylvania’s Newtown Township, for instance, the board of supervisors approved a settlement that granted the construction of a 400-square-foot addition to a Chick-fil-A kitchen and a right turn lane along the main road to address “significant stacking issues.” It also green-lighted a bypass lane to allow customers who received their orders to drive past the pickup window and exit the lot.

Solutions like the numbers on windows and Chick-fil-A’s broader express lane rollout are operator-inspired to these exact kinds of challenges, Abercrombie says. “And then what ends up happening is the support center, which is what we call our corporate office, we get wind of it, and then have the opportunity to reach out, engage with an operator, and then help bring connections to the technology and other assets that might be helpful to make it work even better,” he says.

Chick-fil-A has also invested in canopies to shield workers from the elements as well as granular details like employee apparel, from cooling options seen in athletics to coats designed for winter. There’s little to zero evidence Chick-fil-A’s drive-thru business will taper off in the coming months, no matter how the climate resets in the wake of COVID. It’s a point defined throughout the QSR® Drive-Thru Report—customers came to the drive-thru for safety during the pandemic and they’re staying for the experience. And there’s more to it than convenience. Just look at Chick-fil-A. The experience in the car is as highly regarded as in-store.

When asked if they received “friendly” service at the brand, 88 percent of people in Intouch Insight Annual Drive-Thru Study’s agreed. Only 1.7 percent deemed it “not friendly.’

This is unquestionably a differentiator for Chick-fil-A and not something that’s universal in the industry. “What’s worrisome to see in the study data, is the year-over-year decline in ‘Friendliness’ scores back to 2019,” Livers says. “This decline is easily attributed to all the external factors facing brands over the last few years, but we were hoping to see these scores start to swing back.” However, Abercrombie says, a task ahead will be to spread that good will to other channels. Chick-fil-A offers curbside and a dine-in mobile option where a customer orders at the table and has food brought up, without having to queue in line. “We still believe in what we’ll call analog experiences,” he says. “The traditional experiences. We don’t want to walk away from those being great experiences. We want to be able to really, for every channel, every experience that you have with a Chick-fil-A, we want it to be a remarkable one.”

“There’s always opportunity so you can serve more guests, but can’t do it in a way that we’re going to lose that connection,” Abercrombie adds.

The balance begins

KFC has taken a multifaceted approach as well. Currently, more than 70 percent of the Yum! Brands’ chain’s orders are at the drive-thru—a number that hiked as high as 90 percent during COVID. The brand introduced Quick Pick-Up shelves last November to shorten drive-thru lines and provide an additional outlet. Guests place their order online or via KFC’s app and park in dedicated VIP spots to run in and grab the food. KFC’s NextGen design, which debuted in Q4 2021, features flexible double lanes that adjust based on the store’s demand. So if there’s too much capacity, it opens up a dual order point; if there’s a flush of digital business, it can turn into an express lane like Chick-fil-A’s pilot. That store also boasts a dedicated entry for Quick Pick-Up customers and delivery aggregators, along with dedicated parking and signage to direct guests to collect online orders. Additionally, there’s an integrated Quick-Pick-Up area for online orders with direct access from the kitchen to expedite order fulfillment.

Gagan Sinha, SVP of restaurant technology at Dunkin’ parent Inspire Brands, echoes many of the points made thus far. Namely, as dine-in climbs back, brands are faced with the challenge of keeping up with both in-store and off-premises dining. It’s put the need for a streamlined process at the forefront of the industry’s life-after COVID playbook.

About two-thirds of Dunkin’s 9,200 or so U.S. locations tout a drive-thru. Recent and ongoing enhancements through 2020–2022’s off-premises surge include digital menuboards, kiosks, and improvements to its mobile app. “Consumers have continued to make dining decisions based on convenience and accessibility, giving us belief that the drive-thru uptick is sustainable. Brands like ours have responded by investing in both digital and real estate innovation, resulting drive-thru-only prototypes and added digital channels like new mobile apps and third-party delivery services,” Sinha says.

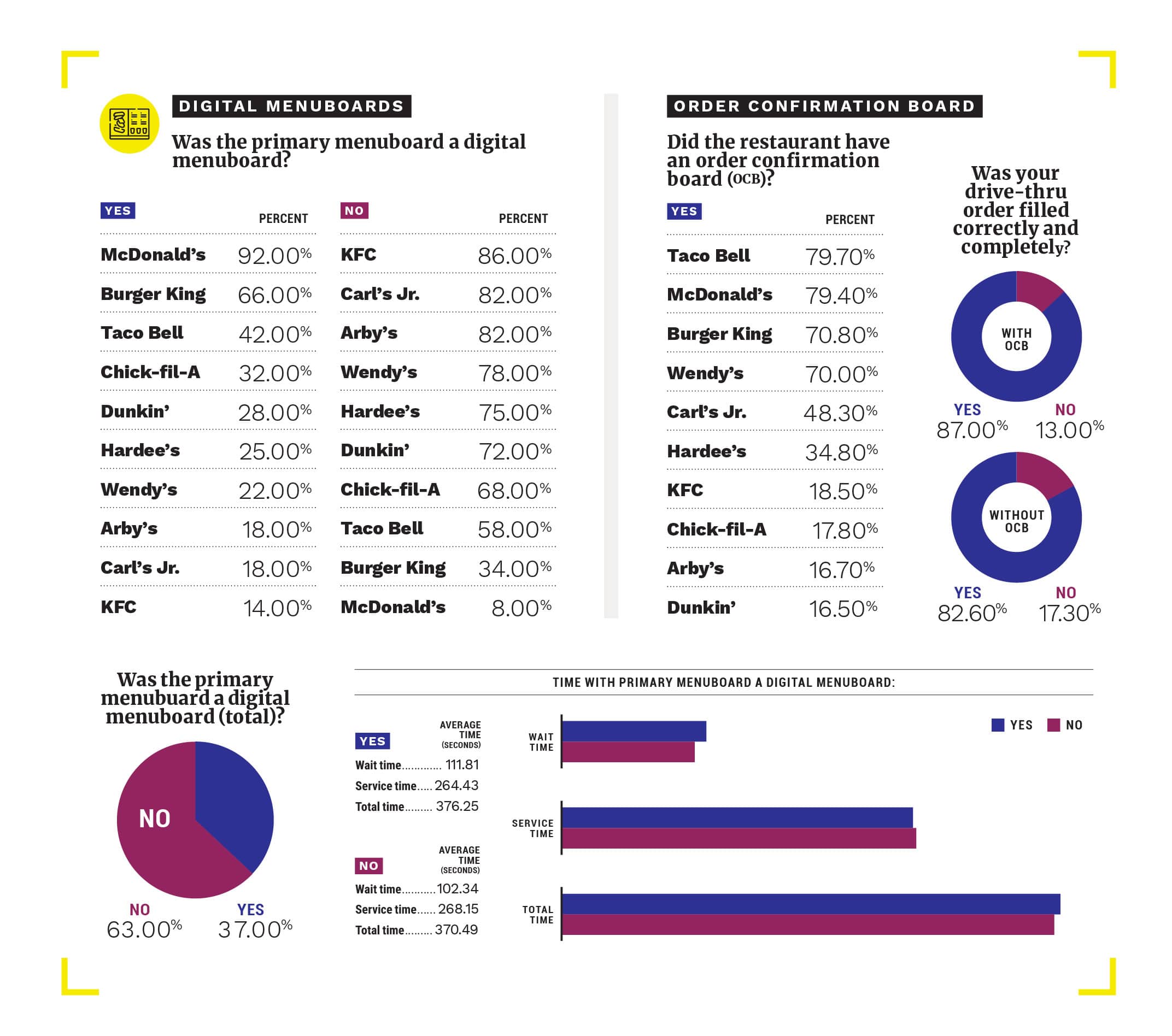

Thirty-nine percent of respondents in the QSR® Drive-Thru Report survey preferred digital menus because “they were easier to read.” Only 9 percent “disagreed completely.”

Dunkin’ is also in the early stages of testing AI learning to bolster the experience and ease duties for employees. Sinha says more details are coming in the next couple of years, but for now, there’s a strong push toward the chain’s Next-Generation design that launched in 2018. It features an open layout with various off-premises options, including a traditional drive-thru lane and one for online and third-party pickups. It uses a more streamlined menu and offers “On-the-Go Ordering” as well, which enables guests to place orders through the Dunkin’ mobile app 24 hours in advance. Similar to what you might see with order pickup at Target these days, a guest notifies a store before they come.

For Dunkin’, a familiar aim in this year’s study has also climbed its priority chart. “We are aiming to provide a more personalized and modern experience across all locations, and to accomplish this we are prioritizing order accuracy,” Sinha says. “The implementation of digital order confirmation has proven to be a sound solution as it has allowed our stores to not only increase the accuracy, but also maintain speed.”

As you can see in the data from Intouch Insight, the run of order confirmation boards has fully kicked in. The Drive-Thru Report consumer section echoes that from the guest level. Order accuracy proved especially vital to Gen X in the survey, with 71 percent getting “angry” when their order was inaccurate. Seventy-three percent said order confirmation screens were “somewhat” or “most important” to their drive-thru visit. A menuboard placed ahead of the ordering speaker (so there was time to review prior to order) was also high at 78 percent. Both are up from 74 and 60 percent, respectively, in 2020. What this indicates is twofold—standards have hiked at the drive-thru due to usage; and secondly, as these systems spread and consumers use them regularly, they place them higher in their demand set. Broadly, it speaks to what’s taken shape industrywide—the drive-thru is better equipped to serve customers than pre-virus, and guests realize that.

“Order confirmation boards alone aren’t enough,” Livers says. “OCBs account for a 2 percent increase in order accuracy, but when paired with a verbal confirmation by the employee that the OCB is correct, the study shows an increase of 7.5 percent in order accuracy.”

According to the survey, drive-thru visits post-pandemic (67 percent) are rated better among consumers than during the peak of the pandemic (61 percent). Over the last couple of years, Sinha says, Dunkin’ has noticed guests are favoring personalized, modern, faster experiences—“that trend isn’t going away,” he says. And he reiterated the point about order accuracy. “Although speed continues to be an important factor for customer satisfaction, order accuracy is also key,” he says. “We will be keeping this top of mind going forward and implementing digital order status boards at our locations was a great step forward. Guests are now able to view and confirm their items before receiving their order, which helps prevent drive-thru errors and delays.”

One “huge” step forward for the brand was its “Dunkin’ Digital’ location in Boston, which opened last September. It’s Dunkin’s first digital-only store that consists of kiosks that handle all orders, eliminating the person-to-person model.

These are the kinds of updates that will stick. Health safety measures, such as protective window guards and touchless food and beverage exchange, proved slightly less important in 2022 than the prior year. Plexiglass and other protective guards at the window were a lead importance metric for just 44 percent of respondents. Two years ago, it was 62 percent. Touchless payment was 40 percent this year; in 2020, it was 50 percent. The touchless exchange dropped from 56 to 39 percent.

But staples like enough napkins (72 from 71 percent) and the right condiments (72 from 69 percent) moved the other direction, pointing to something that’s flashed inside stores as well—guests are less forgiving than they were at COVID peak.

The innovation race

In May, Carl’s Jr. and Hardee’s parent company CKE Restaurants announced a $500 million investment to physically and digitally transform each brand over the next four to six years. More than 500 units across 20 markets would get an update by year’s end. Notably, this project includes new signage and freshly installed interior and exterior digital menuboards. Chad Crawford, CKE’s chief brand officer, says it allows simpler views for consumers, more specificity in daypart, and “certainly elevates that experience to the guest overall.”

The process began in 2020 as CKE examined the industry’s horizon. Like every brand in this study, the company is doing its best to anticipate the future while understanding the drive-thru will undoubtedly key a major part of it. CKE is working to manage the menu and create a more compact list of items to choose from, which will make the drive-thru experience faster and more efficient. “But still offer best-in-class service and elevate in the areas they look for in friendliness and accuracy,” he says. Carl’s Jr. and Hardee’s both clocked in above 85 percent in order accuracy in Intouch Insight’s data. And they were No. 2 and No. 3 behind Chick-fil-A in the friendly metric at 82.8 and 76.4 percent, respectively.

CKE’s efforts are clearly in motion. But yet again, a familiar word rises to the top. “Accuracy is one that’s critical if a consumer chooses to come and spend time and interact with you as a brand,” he says. “You want to make sure that you’re satisfying their needs at a higher level of expectations.” Speaking deeper to Crawford’s point about menus, Gen Z was one cohort that appears to full-heartedly concur. Fifty-one percent of respondents in the QSR® Drive-Thru Report survey said they were overwhelmed by large menus. To the query of whether big menus stress them out at the drive-thru, 10 percent of customers—across all demographics—agreed completely. Twenty-one percent agreed; 22 percent were neutral; 27 percent disagreed; and 20 percent disagreed completely.

Forty-three percent of consumers noted they do not prefer drive-thru menus to have fewer options, as it may deter them from ordering their regular picks.

The reason this is happening in restaurants is more about traffic and wait times than consumer demand. It makes guest feedback and listening that much more critical, Crawford says. CKE is another brand testing AI to add efficiency. Voice ordering is in a test-and-learn phase for the brand, but an ever-present reality industrywide.

In the QSR® Drive-Thru Report, it’s obvious the concept has potential. It isn’t quite there yet, however. Interest in having a personal experience when ordering food from a drive-thru was apparent in the study, as more than two-fifths (45 percent) said they dislike hearing an automated voice when ordering.

At the least, voice and similar automation is simply not in enough locations and deployed broadly enough for customers to know whether they need it or not, or prefer it. You could make the same claim of OCBs a few years back. AI could follow a similar path as adoption spreads and the experience matches the buzz.

When asked what type of drive-thru and ordering options they’d like to see more of in the future, 38 percent picked “tap-to-pay” technology,” up year-over-year from 33 percent. It was 49 percent for Gen Z. Unlike AI, tap-to-pay has become an increasingly familiar process for today’s consumer in many verticals. And so, guests want it after they’ve tried it, and that’s extending to the drive-thru.

Next up was automated tech that detects car arrival for pickup order (37 percent); pre-paid pickup experience (34 percent); extended payment card reader (34 percent); mobile ordering options (33 percent); mobile payment options (32 percent); carhops (30 percent); an ordering systems that remembers a guest and their preferences (27 percent); touchless experience (24 percent); an ordering system that remembers somebody’s last order (23 percent); more extensive digital signage (18 percent); and, lastly, AI that helps make ordering decisions (11 percent). Overall, Crawford believes customers still want what they’ve always wanted from the drive-thru—dependability and hospitality in a fast and efficient manner. “What I would share is that I believe that consumers in general have elevated their expectations,” he says. “… The key element of that experience has not changed, but I do think that the last few years have shown and provided consumers more choice and more ways to interact with brands.”

The 2022 QSR® magazine Drive-Thru Study Methodology:

Intouch Insight is a CX solutions company, specializing in helping multi-location businesses achieve operational excellence so they can exceed customer expectations, strengthen brand reputation and improve financial performance. The 2022 version of Intouch Insight’s Annual Drive-Thru Study included 1,537 completed shops from June until end of July across 10 Brands: Arby’s—174 shops (11 percent); Burger King—168 shops (11 percent); Carl’s Jr.—87 shops (6 percent); Chick-fil-A—174 shops (11 percent); Dunkin’—170 shops (11 percent); Hardee’s—89 shops (6 percent); KFC—167 shops (11 percent); McDonald’s—165 (11 percent); Taco Bell 173 shops (11 percent); Wendy’s—170 shops (11 percent). Nine percent of shops were breakfast (5 a.m.–10:29 a.m.); 49 percent of shops were lunch (10:30 a.m.–1:30 p.m.); 12 percent of shops were late afternoon (1:31 p.m.–4 p.m.); 29 percent of shops were dinner (4:01 p.m.–7 p.m.); and orders consisted of a main item, side, drink, and special request Intouch Insight’s leadership team has hands-on experience partnering with the top quick-serve restaurant brands to collect and centralize data from multiple customer touch points, giving them actionable, real-time insights in an advanced analytics platform. Founded in 1992, Intouch is trusted by over 300 of North America’s most-loved brands for their CX, customer survey, mobile forms, mystery shopping, and operational and compliance audit solutions. For more information, visit www.intouchinsight.com. For the consumer survey portion of the QSR® Drive-Thru Report, The FoodserviceResults team, in partnership with QSR magazine conducted a comprehensive, nationally representative survey of drive-thru consumers in the U.S. using an online survey sample in July 2022. This research included tracking questions and comparative data from the 2021 and 2020 studies, as well as new questions about post-pandemic operations, technology and other key areas of interest. Leveraging insights from numerous industry experts and secondary research, the finalized survey was completed by 1,010 drive-thru consumers during fieldwork. To ensure a relevant respondent base was achieved, all participants were screened to only include those who had at least one drive-thru occasion in the last 30 days. An extensive cross tabulation of the respondent sample data was conducted in order to identify major trends, demographic/behavioral themes and other nuances in the data. Following analysis of all data, this report was developed to communicate key findings and important data from the study.

Intouch Insight is a CX solutions company, specializing in helping multi-location businesses achieve operational excellence so they can exceed customer expectations, strengthen brand reputation and improve financial performance. The 2022 version of Intouch Insight’s Annual Drive-Thru Study included 1,537 completed shops from June until end of July across 10 Brands: Arby’s—174 shops (11 percent); Burger King—168 shops (11 percent); Carl’s Jr.—87 shops (6 percent); Chick-fil-A—174 shops (11 percent); Dunkin’—170 shops (11 percent); Hardee’s—89 shops (6 percent); KFC—167 shops (11 percent); McDonald’s—165 (11 percent); Taco Bell 173 shops (11 percent); Wendy’s—170 shops (11 percent). Nine percent of shops were breakfast (5 a.m.–10:29 a.m.); 49 percent of shops were lunch (10:30 a.m.–1:30 p.m.); 12 percent of shops were late afternoon (1:31 p.m.–4 p.m.); 29 percent of shops were dinner (4:01 p.m.–7 p.m.); and orders consisted of a main item, side, drink, and special request Intouch Insight’s leadership team has hands-on experience partnering with the top quick-serve restaurant brands to collect and centralize data from multiple customer touch points, giving them actionable, real-time insights in an advanced analytics platform. Founded in 1992, Intouch is trusted by over 300 of North America’s most-loved brands for their CX, customer survey, mobile forms, mystery shopping, and operational and compliance audit solutions. For more information, visit www.intouchinsight.com. For the consumer survey portion of the QSR® Drive-Thru Report, The FoodserviceResults team, in partnership with QSR magazine conducted a comprehensive, nationally representative survey of drive-thru consumers in the U.S. using an online survey sample in July 2022. This research included tracking questions and comparative data from the 2021 and 2020 studies, as well as new questions about post-pandemic operations, technology and other key areas of interest. Leveraging insights from numerous industry experts and secondary research, the finalized survey was completed by 1,010 drive-thru consumers during fieldwork. To ensure a relevant respondent base was achieved, all participants were screened to only include those who had at least one drive-thru occasion in the last 30 days. An extensive cross tabulation of the respondent sample data was conducted in order to identify major trends, demographic/behavioral themes and other nuances in the data. Following analysis of all data, this report was developed to communicate key findings and important data from the study.